Student Activism in the Context of the 1930s

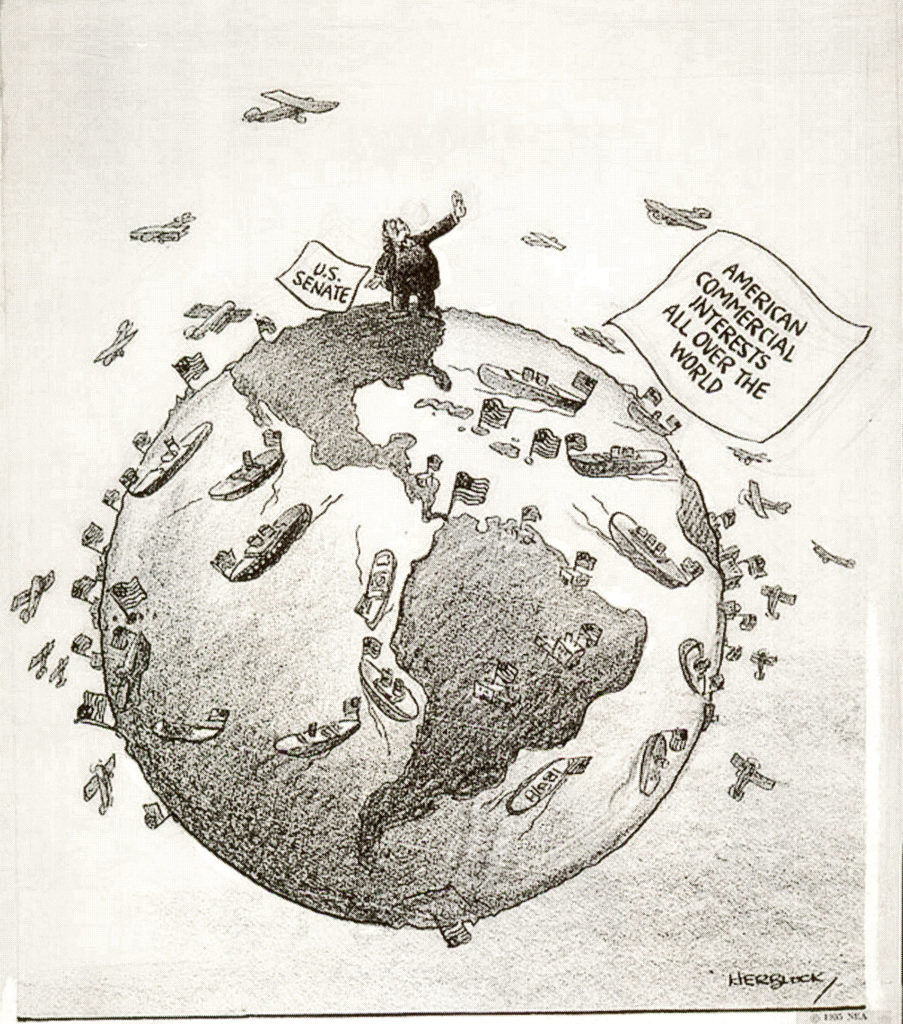

This period of political ferment was well under way in the 1920s when the economic crisis of the Great Depression of 1929 devastated Americans’ lives, and intensified the period’s anticommunism, labor activism, racism and antisemitism. American foreign policy was shaped by competing views of the nation’s relationship to the world as fascism and dictatorship took hold in Italy, Japan, Germany, and Spain, from the mid-1920s and throughout the 1930s, resulting in WWII. The United States Senate demanded complete neutrality and isolation while President Franklin D. Roosevelt sought greater support for Britain and European allies.

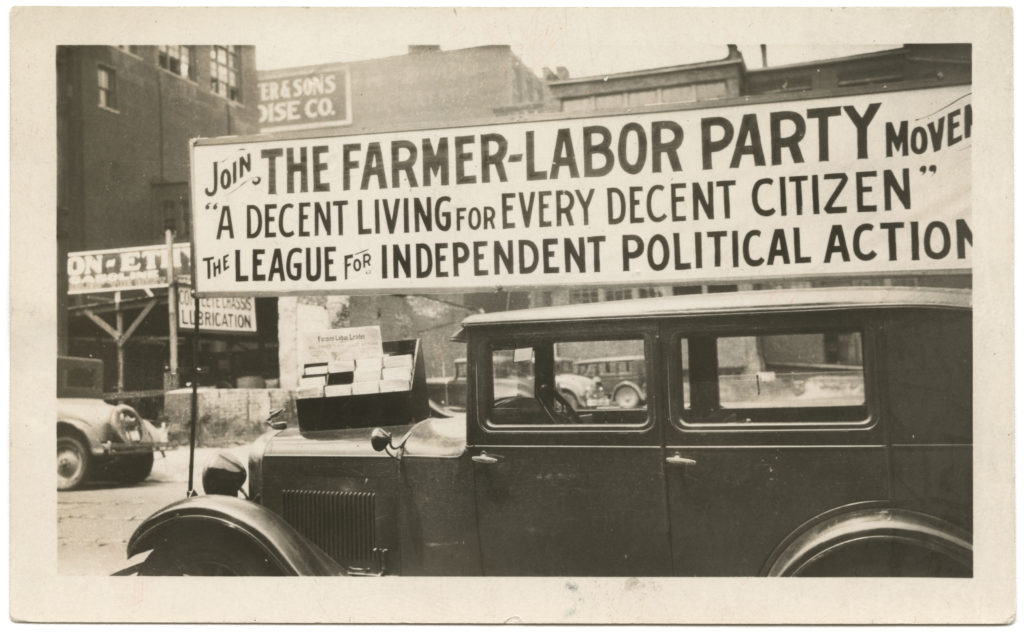

Minnesota was an epicenter of the politics of the 1930s when the Farmer-Labor Party, one of the nation’s most successful progressive third parties, was victorious in electing dozens of statewide and local officials and controlling the governor’s office from 1930–1938. Some Republicans, the other dominant political party, which favored business and capitalism, sought to purge left-wing politicians, union activists, and progressive students and faculty from public life and accused them, no matter what their views were, of being un-American Communists.

The Great Depression

In 1929, the crash of the stock market abruptly transformed Americans’ lives. In October of that year unemployment stood at 3%. By 1931, 25% of the workforce was unemployed. The poorest areas of Minneapolis faced much greater unemployment. On Minnesota’s Iron Range, iron ore mining districts around Lake Superior, it was as high as 70%. Combined with drought in the Great Plains, the region and the state faced poverty, hunger, and unemployment, as did the nation, on an unprecedented scale. Campus life was remembered by two former students.

Eric Sevareid, an undergraduate and activist at the University of Minnesota from 1934–1936, recalled the Depression.

[In 1933] We observed bread lines from the street car as we went to school carrying the books that described the good society. We duly listened to lectures on orthodox economics, which explained the “natural laws” of capitalist competition, which would, if not interfered with, ultimately produce the general good by permitting everyone to pursue his selfish ends unhindered. And every day the headlines spoke of riots, of millions thrown out of work, of mass migrations by the desperate. All of this was happening in the richest country on earth, a country that possessed all the political rights and instruments by which free men could change their condition-and still they could not prevent this…The system did not work, and if it did not work in America it certainly would not work anywhere.

Eric Sevareid

Not So Wild A Dream Eric Sevareid, Not So Wild a Dream (First published 1946; reprint Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1995), 55-56.

Rosalind Matusow Belmont, a student at the University and activist during the 1930s, described her memories of the period on campus.

There were some fraternities, but the majority of students at that time were pretty much from pretty low income families and [they had] an alliance, an identification whenever there was some kind of a labor activity. I remember later on when Strutwear [a knitting works] went on strike [in 1935], and some of the other strikes occurred, the students were interested and they wanted to go down to the picket lines and they wanted to find out what was going on, they were very much interested.

Most of the students were trying to find a way to keep going to school, a lot of the students worked, a lot of the students worked in cafeterias so that they’d be able to get their meals as a way of working.

[We would go to the] White Castle, where you could get six hamburgers for 25 cents, and we used to go in you know and get six and split, but everybody was very, very poor, people did not have money, there was a streetcar, we thought it was spending too much money to take the streetcar, and we hitchhiked to save a nickel.

Everybody around me that I can remember was having a lot of trouble with money, even in the University dormitory where I went the first semester. Most of the people who lived there at the University were farmers’ daughters you know, and I can remember they made their own clothes and most of them were working part-time to be able to make it through college. It was you know, and people didn’t have jobs.

Rosalind Matusow Belmont

Minnesota Historical Society, Oral History Project Oral history interview with Rosalind Matusow Belmont, April 4, 1982, 20th Century Radicalism In Minnesota Oral History Project, Minnesota Historical Society, pages 6-7, http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/oh30.xml.

Farmer-Labor Party

Minnesotans responded to the Great Depression in part by voting into office in the 1930s governors, senators, congress members and city-level officials affiliated with the Farmer-Labor Party, one of the nation’s most successful progressive third parties. Its members never controlled the State Senate of the Minnesota Legislature. Its roots went to the 19th century, but the party developed from 1917 through the 1930s and began to lose strength by the early 1940s.

The strong coalition in Minnesota between workers and farmers, who originally created the Nonpartisan League in North Dakota in 1917 to secure fair prices for wheat, grew as a result of unemployment and poverty. It brought a new enthusiasm for the party platform that included funding for building roads, relief from farm foreclosures, and the creation of a state income tax to finance employment. Its leaders were anti-corporate and pro-organized labor. They advocated for many of the programs that would be introduced by the New Deal, including Social Security and the right to organize unions.

There were three Farmer-Labor governors between 1931 and 1938: Floyd B. Olson, who served from 1931 to 1936, Hjalmar Petersen, who served from 1936 to 1937 to finish Olson’s term as a result of his death, and Elmer Benson, who served from 1937 to 1939. Olson and Benson had a substantial impact on the University of Minnesota. Republicans in state politics, as well as Republican administrators on campus, were in constant conflict with the vision of the Farmer-Labor movement.Richard M. Valelly, Radicalism in the States: The Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party and the American Political Economy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989).

The Politics of War

World War II formally began in 1939. The rise of fascist states in Europe, however, began far earlier, and the question of war dominated the decade until the United States declared war in 1941. Much of the decade was taken up with the question of whether the United States would join the fight against the enemies of democracy.

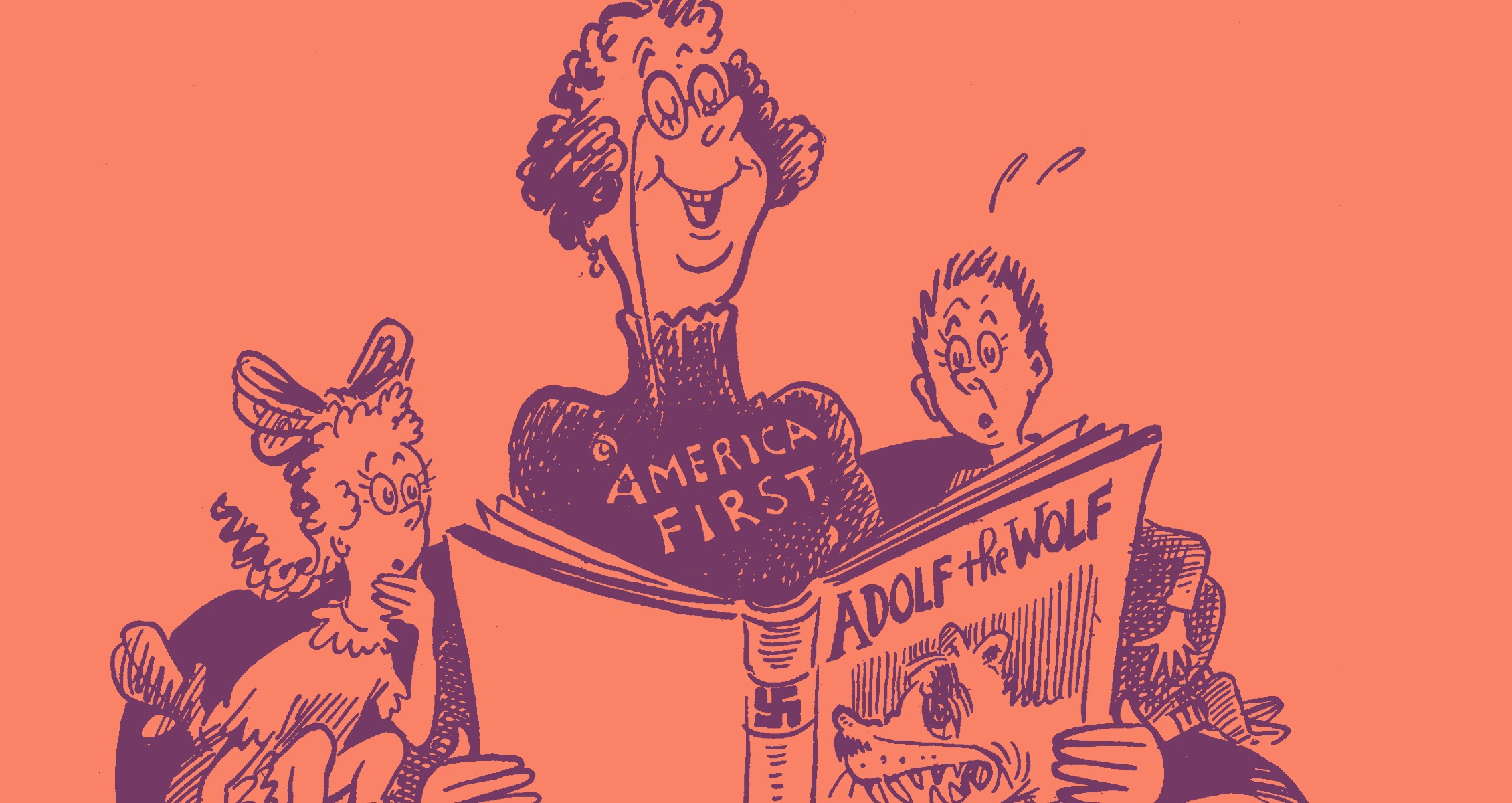

Throughout the 1920s and the 1930s the majority of Americans opposed war and embraced isolationism. Anti-war factions of the period in the United States included both the right and reft wings of American political life. The America First Committee, whose hundreds of thousands of supporters centered in the Midwest and included Nazi supporters, conservative businesspeople, and antisemitic populists, opposed any form of intervention in global relationships. At the same time, left-wing activists were anti-war as well until 1941 when Hitler unilaterally broke his non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union. Pacifists opposed all war on principle. Progressive activists believed that WWI enriched bankers, industrialists, and capitalists and that could be the only motivation for war.

Overall, little could shake politicians during the mid-1930s from isolationism despite the rise of fascism, Germany’s invasion of its neighbors, Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia, Japan’s invasion of China, and attacks on American ships by German submarines. Official state persecution of Jews by the Nazi regime beginning in 1933 moved remarkably few non-Jewish Americans, and the news of Nazi death camps and the extermination of Jews, as well as Roma, disabled and gay people, also seemed to have little effect.

Popular opinion did shift at the end of the decade as the theaters of war and international alliances changed. In 1940, after the Nazi occupation of France, Belgium, Norway, Holland, and Denmark, many Americans questioned neutrality. When the United States entered the war in 1941 after a Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, most, but by no means all, of the opposition ended.Ira Katznelson, Fear Itself: The New Deal and the Origins of Our Time (New York: W.W. Norton, 2013), 290-301.

Anti-Communism

The anxiety over communism and who was a Communist dominated the decade. The Communist Party of the United States was involved in the struggle for African American rights, student activism, and the labor movement. However, many left-wing activists were not Communists. Accusations of communism became a slur used against virtually anyone critical of capitalism or corporate power. The FBI was empowered to investigate subversives beginning in 1936 at the direction of President Franklin Roosevelt. Director J. Edgar Hoover focused primarily on people and groups he considered Communists as well as Nazis. In this period of student activism on campus, membership in organizations such as the Communist Club were not prohibited by any laws. Administrators who had employees spy on student groups, did so because of their own political views.Larry Ceplair, Anti-Communism in Twentieth-Century America (Santa Barbara: Praeger Press, 2011).