Segregated Student Housing and the Activists Who Defeated It

The Early Fight for African American Rights in Minnesota

The number of African Americans in Minnesota nearly doubled between 1900 and 1920 to 9,000, with the majority settling in the Twin Cities. The states from which most African Americans hailed at the end of the 19th century were eastern and midwestern, not southern. It was not until the 1940s that there was a significant increase of the population—to 14,000 people—not even one percent of the state’s residents.

African American migrants to Minnesota had reason to be hopeful about life in a state that was granted statehood in 1858.Recent research reveals that Minnesota had strong connections to slave holders and slavery, and the Minnesota economy benefitted from the wealth of enslavers, including funds for the University of Minnesota. Christopher P. Lehman, Slavery’s Reach: Southern Slaveholders in the North Star State (St Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2019).

Its citizens strongly supported the Union during the Civil War. Through the work of a small number of African American activists and their allies in the Republican Party, they achieved an impressive number of civil rights protections. In 1865, the Constitution of the State of Minnesota banned segregation, including in schools. In 1868, African American men received the right to vote when citizens voted for the the equal suffrage amendment to the Minnesota state constitution, which preceded the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution by two years. In 1885, the State Legislature passed the Equal Accommodation Act that threatened fines and imprisonment for those who deprived African Americans of the right to use all public places and hotels. In 1897, the Legislature added saloons to the list of establishments where segregation was unlawful, although the fines that could be levied against violators were decreased.William D. Green, Degrees of Freedom: The Origins of Civil Rights in Minnesota, 1863-1912 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 88-90.

However, those rights offered African Americans virtually no access to economic and vocational advancement. School integration was never achieved because white parents refused to allow their children to learn in the same classrooms as African American children and schools for the latter were impoverished. No legislation protected African Americans’ right to live where they wished or their right to employment until the modern Civil Rights era.William D. Green, Degrees of Freedom: The Origins of Civil Rights in Minnesota, 1863-1912 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press 2015), 456-459, 464.

Therefore, the reality of African American life in Minnesota was little different from their experience in less progressive states. Employment in the late 19th century and in the 1920s and beyond reflected national trends. Clustered in domestic and personal services such as barbers, janitors, and servants, not even two percent of African American men and women worked as professionals in fields such as acting, law, the clergy, and medicine. Poverty level wages for workers made home ownership nearly impossible, and the possibility of accumulating any savings or investments was out of reach. Surveys of employers and unions in 1926 revealed that almost 80 percent would not hire an African American employee and unions would not accept them for fear of white workers leaving.David Vassar Taylor, African Americans in Minnesota (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2002), 17-28, 57-63.

Racism took a more pernicious form in the 1920s when Minnesota counted 100,000 members of the Ku Klux Klan by 1928. In 1920, a mob of thousands of white Minnesotans in Duluth lynched three of the six African American circus workers who were accused without evidence of raping a young white woman as police stood by. The event was met with condemnation by some and hearty support by journalists and police in the region.“The Lynchings,” Minnesota Historical Society, https://www.mnhs.org/duluthlynchings/lynchings.

The University of Minnesota’s Vision for African American Students in the Early Twentieth Century

A very small number of African American students attended the University of Minnesota beginning in the late Nineteenth Century.This Free North is a documentary about African American history at the University of Minnesota. It was released on the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of African American Studies at the University. For more information or to watch the documentary see https://www.tpt.org/this-free-north/about/

Andrew Hilyer was the first Black man to graduate in 1882. Scottie Primus Davis was the first Black woman to graduate in 1904. By the end of the 1920s, 39 African American students attended the University as undergraduates and in professional schools. Because the University of Minnesota was founded as a land grant college in 1851, its mission was to serve the people of the State of Minnesota. However, it did not serve all Minnesotans equally.Tim Brady, Young, Gifted and Black: Ninety Years of Experience and Perceptions of African American Students of Minnesota 1882-1972 (Minneapolis: Coalition for the History of African American Contributions to the University of Minnesota and General College, 2003), 1-5; Steve Trimble, “The Search for Scottie Primus Davis,” Ramsey County History 56, no. 4 (Winter 2022): 21-29.

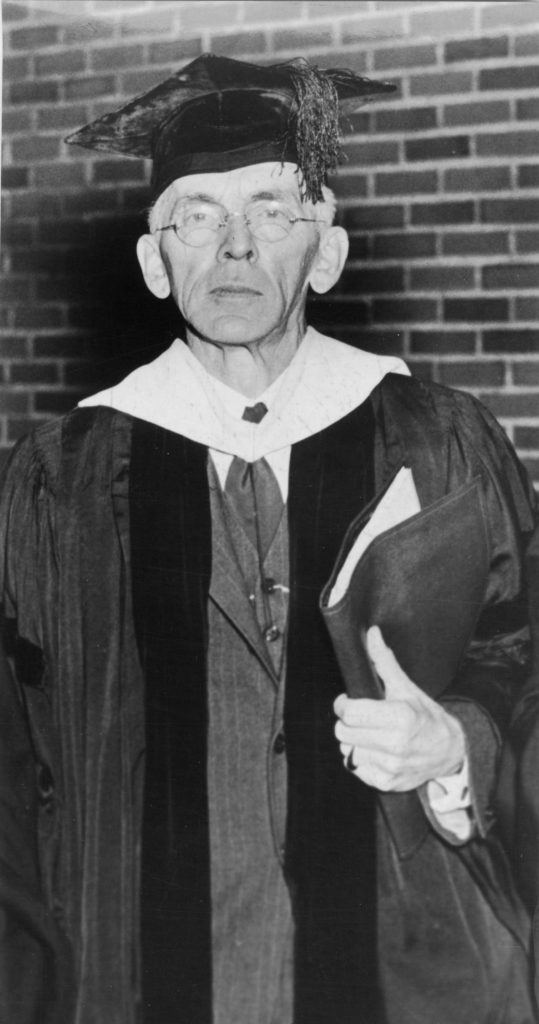

Lotus D. Coffman (1875–1938) served as president of the University from 1920–1938. The state’s population grew rapidly during this time and, anticipating that increase, Coffman wanted the University and the state’s secondary school system to be poised to respond. To that end, he appointed a Committee of Seven in 1924 to explore the issues relevant to education. It was headed by C. W. Boardman, a Minnesota educator.

The Committee spent three years developing their report, based on vital statistics on the state’s population, which included demographic information about parents’ occupations, places of birth, income, and residence, as well as other data. Their final report in 1927, among other things, called for extending opportunities in higher education to students who lived outside of the Twin Cities, who were children of immigrants, or who were from lower social classes. The Committee appeared to champion a vision for equality of opportunity for the children of the State of Minnesota.

However, the authors’ final report manipulated the 1920 census data available to them in their analysis of who was likely to attend the University. The data included in their report, on which they based their recommendations, excluded all citizens of color from the State of Minnesota. Specifically, their analysis left out nearly 9,000 African Americans, which was twice the number of those in the census who were categorized as “other,” and more than many of the immigrant groups who were left in the report’s tables. This “scientifically” produced vision for the 20th-century University of Minnesota simply excluded African Americans and other people of color.Mark Soderstrom, “The Three Rs—Republicanism, Racism, and Rhetoric: Segregation and Nationalist Education at the University of Minnesota,” Weeds in Linnaeus’ Garden: Science and Segregation, Eugenics and the Rhetoric of Racism at the University of Minnesota and the Big Ten, 1900-1945 (PhD Dissertation, History Department, University of Minnesota, 2004), 18-47.

The Committee of Seven’s report and President Coffman’s vision of social segregation were rooted in the related ideologies of this period of “race science” and eugenics. These theories were integral to the ideologically driven view of a racial hierarchy and classification system for the world’s population. European and European Americans imagined a “science” that demonstrated their superiority and sought to maintain a “pure” white race. Many sought immigration restrictions from countries in Europe where the populations were Catholic and Jewish, as well as non-white. They also opposed social interactions between whites and non-whites in the United States. These ideas were widespread in much of academic life in this period and permeated social policy.Erika Lee, America for Americans: A History of Xenophobia in The United States (New York: Basic Books, 2019), 113-120.

Despite these obstacles, a small but growing number of African Americans from inside and outside the state of Minnesota continued to enroll at the University of Minnesota. By the late 1930s, about 70 African American students were on the campus. In that decade, one of the central features of university life—where and with whom students lived—became the center of the fight for racial justice staged by African American students and their allies.

Open Doors-Closed Doors: A Tradition of Segregated Housing at the University of Minnesota

Jewish and African American undergraduate students were accepted at the University of Minnesota without any known quotas on either group, in contrast to many private colleges and universities throughout the country. No African American students were admitted to Southern white colleges from the height of the Jim Crow era between 1890 and 1935 until the 1956 decision by the Supreme Court to integrate schools in Brown v. Board of Education. Segregated African American colleges were necessitated by the 1896 legal precedent set by Plessy v. Ferguson. The funding for higher education created by the Morrill Land-Grant of 1890 created educational opportunities for Southern African Americans in segregated colleges, which lacked resources but made higher education available. Small numbers of African American students also attended Northern colleges and universities during the late 19th century and early decades of the 20th century.Brandon C.M. Allen and Levon T. Esters, “Historically Black Land-Grant Universities: Overcoming Barriers and Achieving Success,” (Poster presentation, National Conference on Race and Ethnicity in American Higher Education, New Orleans, LA, 2018), https://cmsi.gse.rutgers.edu/sites/default/files/HBLGUs_0.pdf.

Quotas in Northern universities grew in prominence in the United States in the 1920s. They limited African American students’ (already hindered in educational opportunities) and Catholic students’ enrollments, but they were especially directed toward Jewish students, who were beginning to seek education in private colleges and universities in growing numbers.

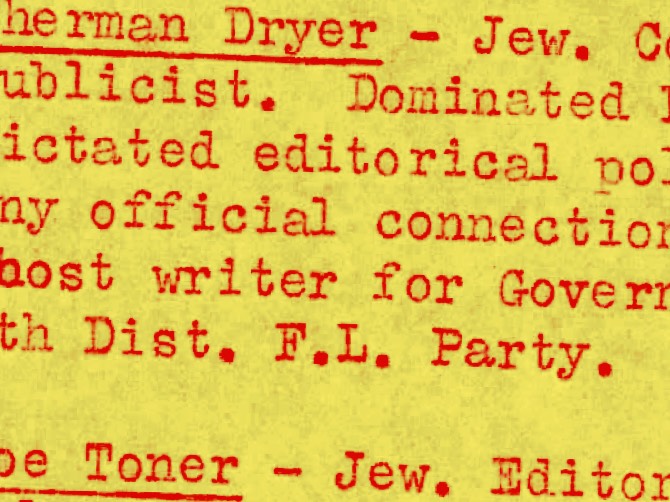

Despite the University of Minnesota having no formal quotas for Jewish and African American applicants, administrators found ways to track these groups. Applicants for admission were required to include their race and religion on their forms. Just as the United States passed laws that excluded immigrants deemed “undesirable” from Eastern and Southern Europe, as well as from Japan in 1921 and 1924, most administrators in higher education fought, in one way or another, to exclude or monitor Jews and African Americans.Marcia Graham Synnott, The Half-Opened Door and Admissions at Harvard, Yale and Princeton, 1900-1970 (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1979), 13.

African American student housing was the most visible expression of the University of Minnesota’s racial discrimination and embrace of social segregation. The battle for racial equality in housing stretched beyond the campus to politics in the Twin Cities, the state, and even the nation.

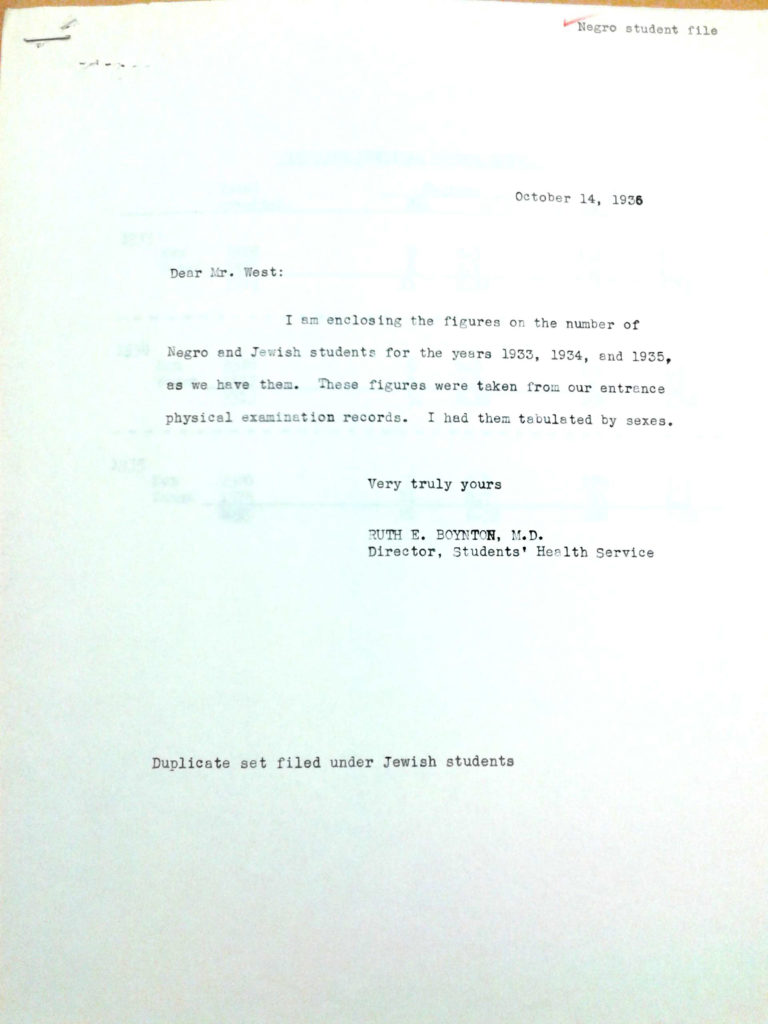

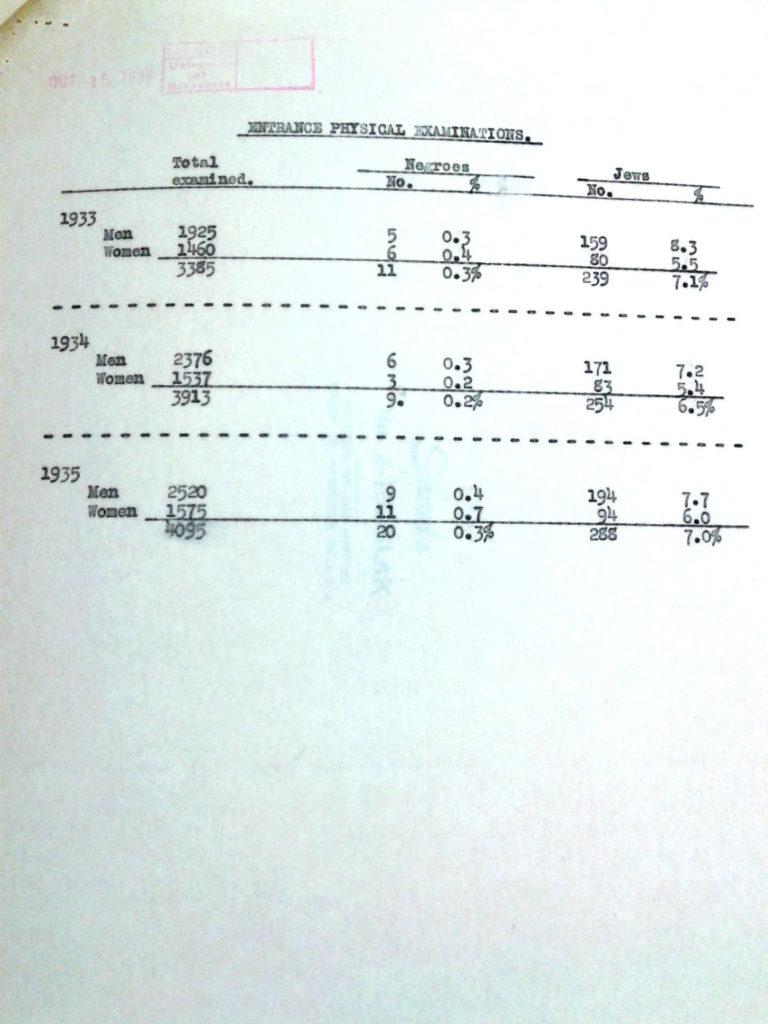

As Jewish and African American enrollments increased, at President Coffman’s insistence his staff began to monitor those students’ small but growing numbers. He also required them to track the numbers of Jewish and African American out-of-state students, as he warily anticipated what he viewed as minorities’ unwelcome desire for on-campus housing. University administrators considered the presence on campus of Jewish and African American students to be a “problem” that required their attention. Within a few years, directors of student unions, including the University of Minnesota’s, also began monitoring the numbers of Jewish and African American students using their facilities, due to similar anxiety about their social interactions with “regular students.”

At the same time as the University monitored students of color and other students from marginalized groups, it also exerted more control over where any student could live, which culminated in a 1932 policy. The University now required students to live only in housing that met its approval. They could live at home, in a dormitory, in a cooperative housing unit, or in privately owned boarding houses, all vetted by administrators. The University, therefore, played an increasingly important role in controlling students’ lives by deciding what was acceptable housing, ultimately exercising the right to support racially segregated housing.The case of a boarding house excluding Jewish students is discussed in the essay “Antisemitism at the University of Minnesota.”

President Lotus Coffman was committed to the expansion of the University and the value of a liberal arts education, but segregated housing was central to that vision. In Coffman’s view, a fundamental racial hierarchy in society as well as in the University, was not only necessary but should be built on unique privileges to white students. Until his death in 1938, he argued for the complete social separation of students of different races. Consistent with that view, he supported the right of owners of off-campus housing to exclude students from marginalized groups beginning at least in the 1920s, and he was the architect of taxpayer-funded segregated housing on campus beginning in 1931.

Student activists made integrated housing a campus issue from the late 1920s through the 1960s. African American students and their allies who, over the decades, participated in the Negro Student Council, the Progressive Party, the Student NAACP, the Student Farmer-Labor organization, the Civil Rights Committee, and many others worked with the NAACP, the African American press, the Urban League, Phyllis Wheatley Settlement House, Hallie Q Brown Community House, progressive governors, and legislators to force the University of Minnesota to stop racial and religious discrimination. These organizations repeatedly confronted University presidents over this period with demands to end segregated housing as well as to address other issues.

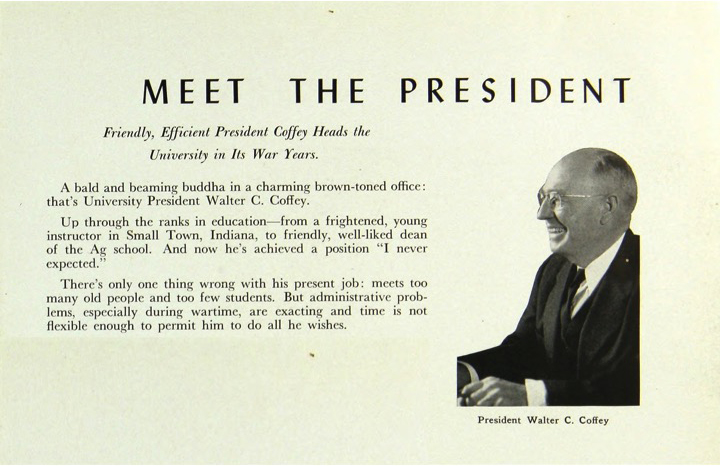

Four University of Minnesota presidents responded to the issue of housing, race, and religion over more than two decades. Following Coffman’s support for segregation, President Guy Stanton Ford (1873–1962) ended it in 1937 as acting president. Ford’s policies were reversed, however, by Walter Coffey (1876–1956), who served as president from 1941 to 1945. Coffey formally supported segregation until 1942 when he relented to a mass movement to officially end this practice, but informal segregation persisted for the remainder of his presidency. James Lewis Morrill (1891-1979) served as president from 1945 until he retired in 1960 and demanded an end to racial and religious segregation in University-approved boarding houses.

These four presidents, three of whom were born within a few years of one another, all white and all midwestern, took different stands for and against racial integration in student housing. The fight for and against segregated housing in the decades that stretched from the 1920s to the 1960s reveals that there was never a single consensus on racism and antisemitism during these decades in Minnesota. Rather, the struggle against these rules and attitudes was consistently waged by university presidents and administrators, student activists, African American defense organizations, and governors and legislators. Students never stopped struggling for justice and were supported by many of those in power.

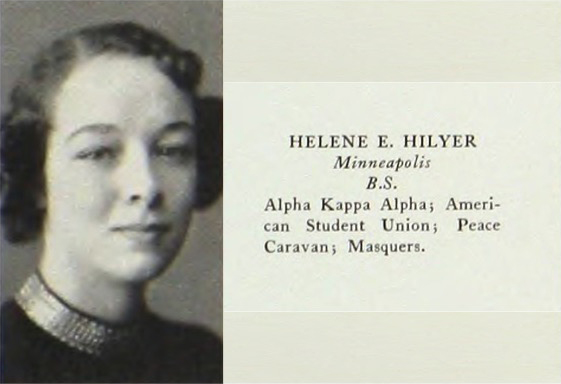

There are few photographs in this section on housing of the African American students who led the struggle to change the University of Minnesota and challenge its racial hierarchy. An African American Greek-letter fraternity and sorority had existed since the 1920s at the University but were never included in the Gopher yearbook. Only a few African American students’ pictures appeared in the yearbook. They were rarely part of campus organizations, which were highly segregated. Their story is told, then, in part, through the names and activities of every African American student activist who appeared in the Minnesota Daily, or the African American press, as well as those names found in the papers of deans and presidents of the University in folders marked “Negro.”

The names stand in for the images that do not exist.

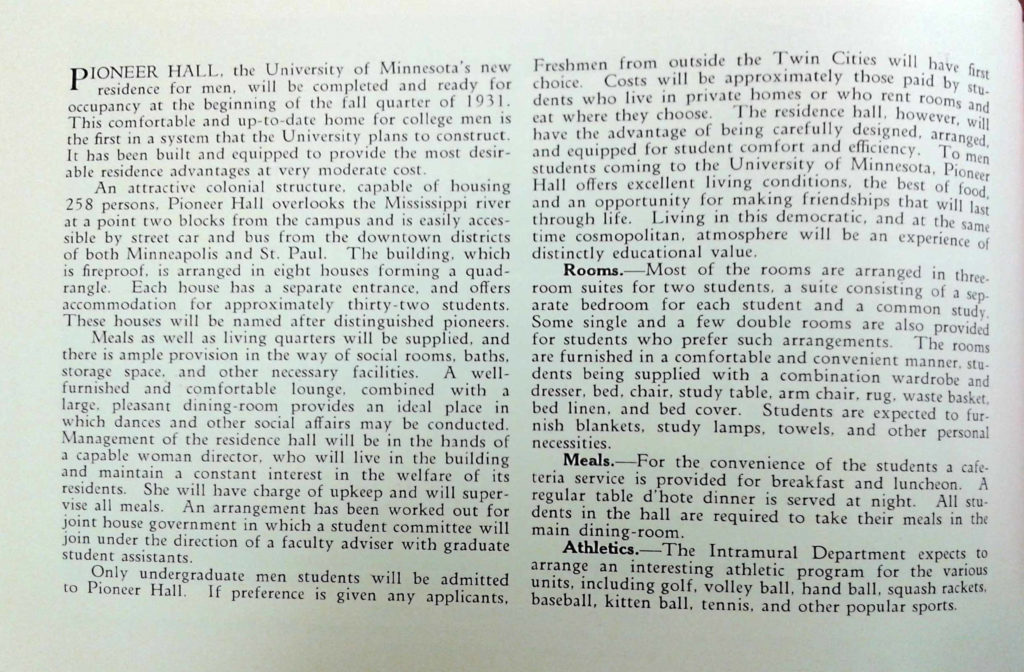

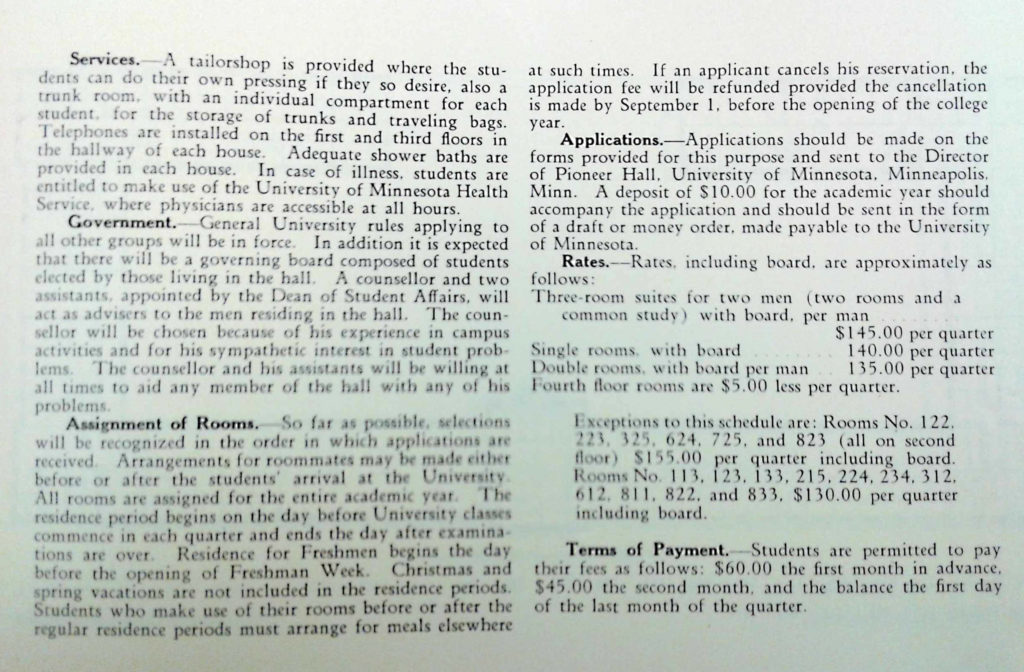

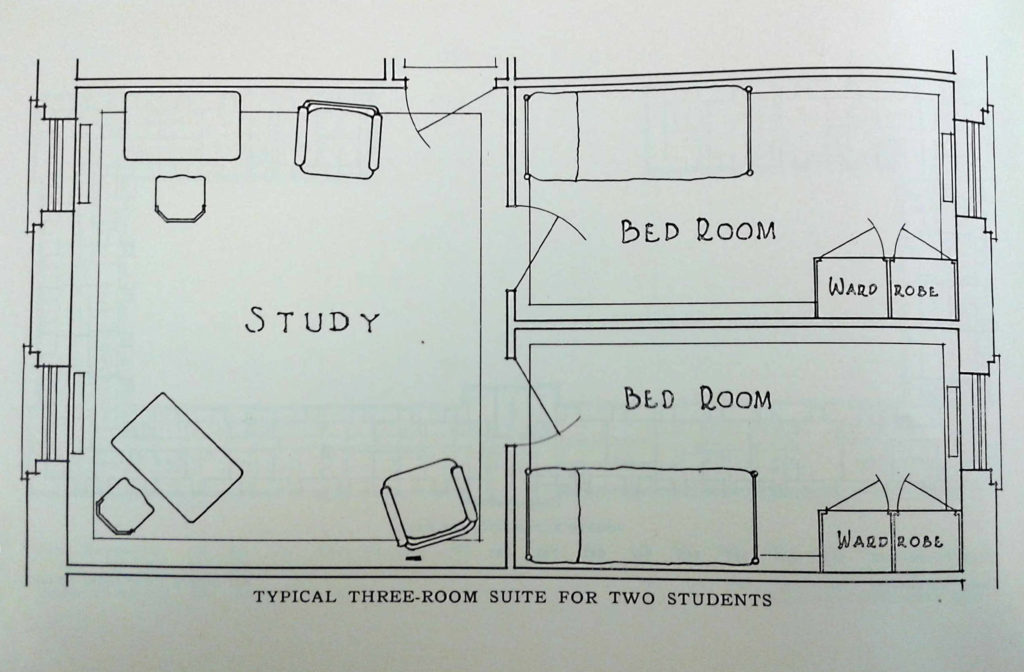

Slamming the Dormitory Doors on African American Students from 1931-1935: John Pinkett Jr., Norman Lyght, Ahwna Fiti, and the Beginnings of President Coffman’s Insistence on Segregated Housing

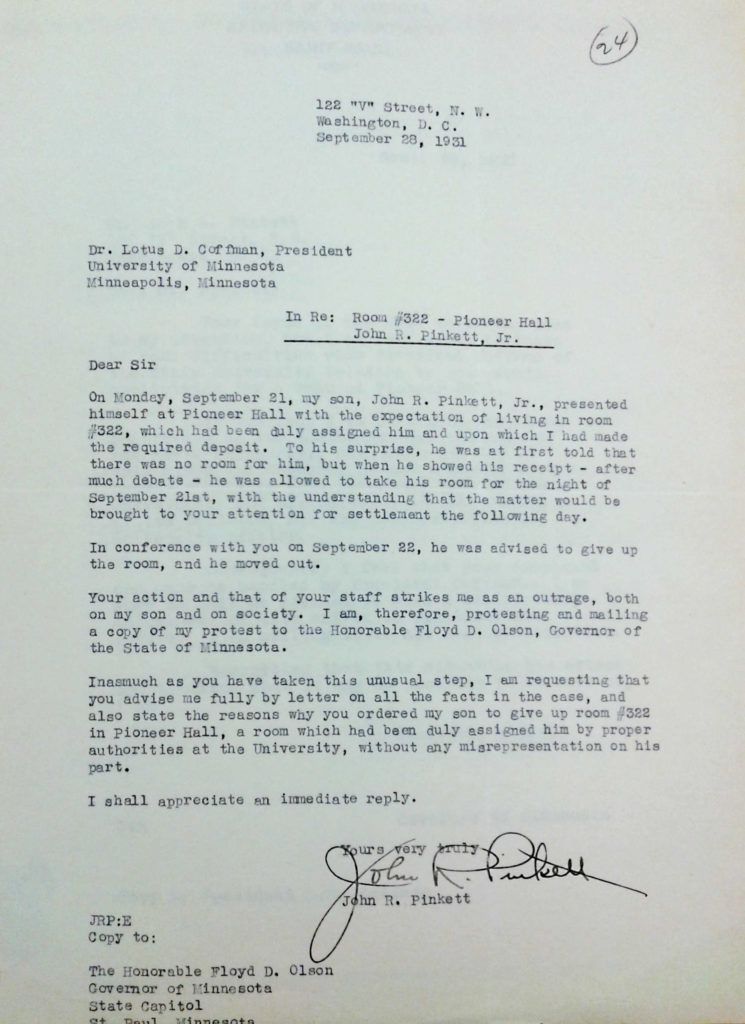

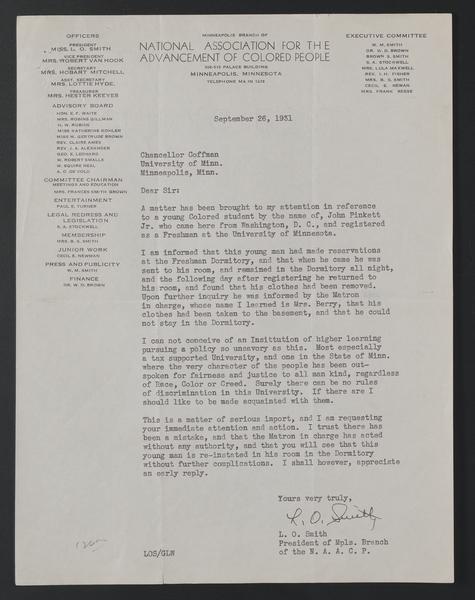

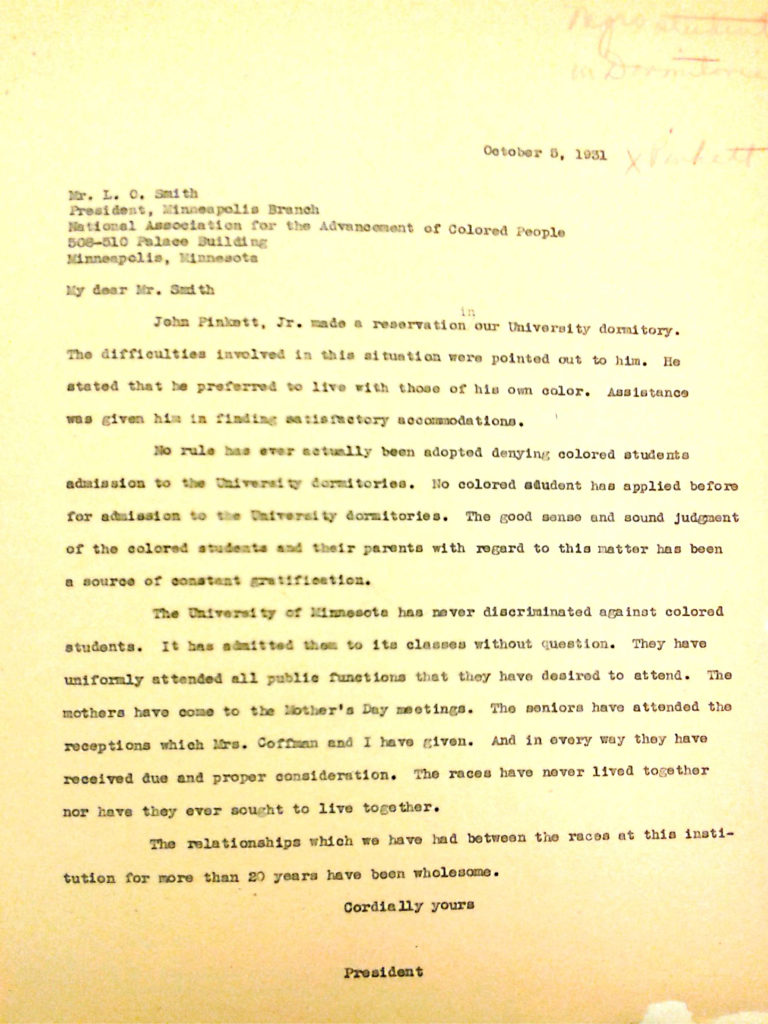

In October 1931, at the start of his freshman year, John Pinkett, Jr., of Washington, D.C., moved into Pioneer Hall, the newly built men’s dormitory. Only a few hours later, President Coffman was notified by housing authorities that an African American student intended to live there. The University president came to the dormitory to speak to John Pinkett. After spending a single night, Mr. Pinkett moved off campus. It was clear that he was asked to leave. The correspondence between Coffman and John Pinkett’s father, and Coffman and L.O. Smith, president of the NAACP, reveals not only outrage over how the student was treated, but surprise at the racism. Coffman’s defense was disturbing for its unapologetic support of segregation. He wrote to the NAACP president who led campaigns for racial equality in the Twin Cities, “the races have never lived together nor have they ever sought to live together.”

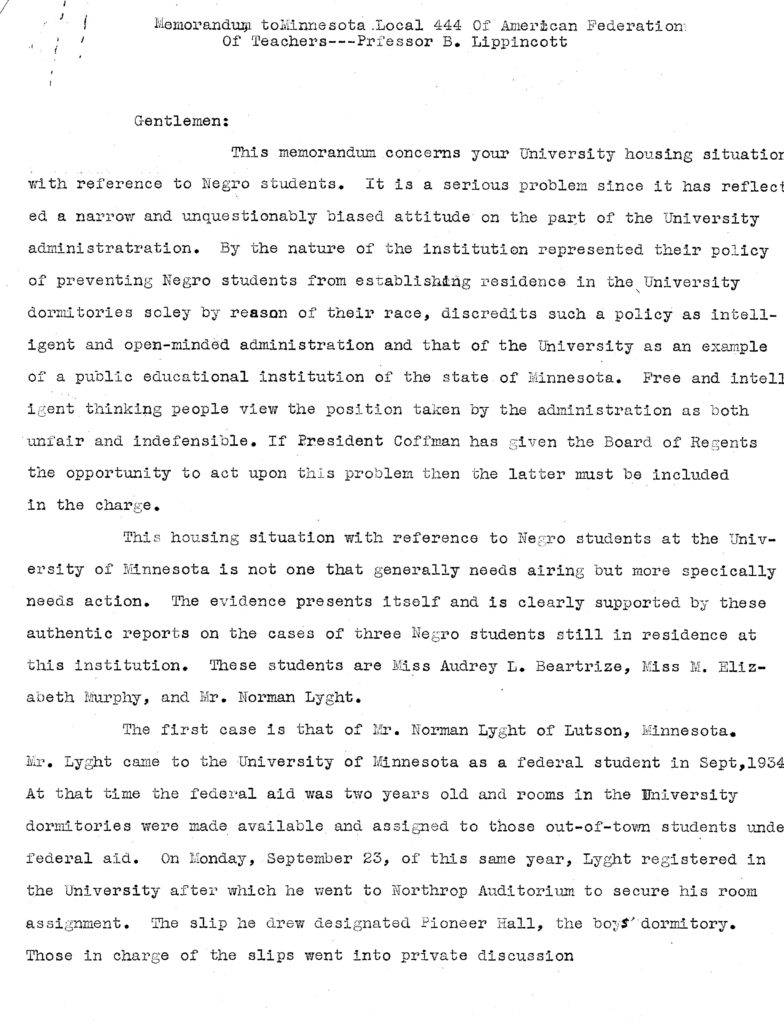

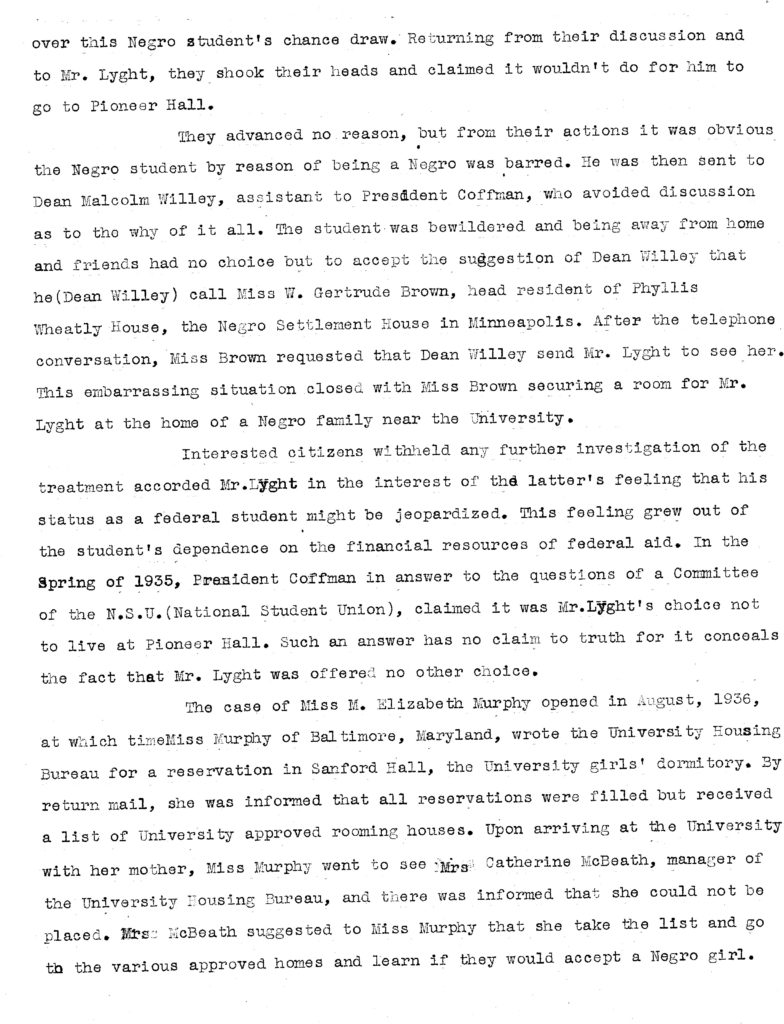

In 1934, the next student to be barred from campus housing was Norman Lyght. Mr. Lyght arrived at the University from Lutsen, Minnesota, at the height of the Depression, with a federal aid grant that required him to live in a campus dormitory. He was not allowed to spend a single night on campus by the University housing authorities. No one explained to him why he could not stay in the dormitory to which he had been assigned.

Norman Lyght’s story was uncovered in the archive in a report written by undergraduate Warren Grissom, chairman of the Interracial Committee. Grissom, an African American, presented the report about the state of segregated housing to Local 44 of the American Federation of Teachers in 1937 at the invitation of Department of Political Science professor Benjamin Lippincott.

In 1931 and 1934, when Pinkett and Lyght were barred from Pioneer Hall the University contacted Gertrude Brown (1888–1939), Director of the Phyllis Wheatley House, an African American Settlement House on the north side of Minneapolis. University deans expected her to find housing for these and other African American students that the University refused to accommodate. The Wheatley House provided social services and meeting rooms for African American organizations, and housed college students and visiting luminaries who were excluded through segregation from living on campus or staying in local hotels.Howard Jacob Karger, “Phyllis Wheatley House: A History of the Minneapolis Black Settlement House, 1924 to 1940,” Phylon 47, no. 1 (1st Qtr., 1986), 79-90.

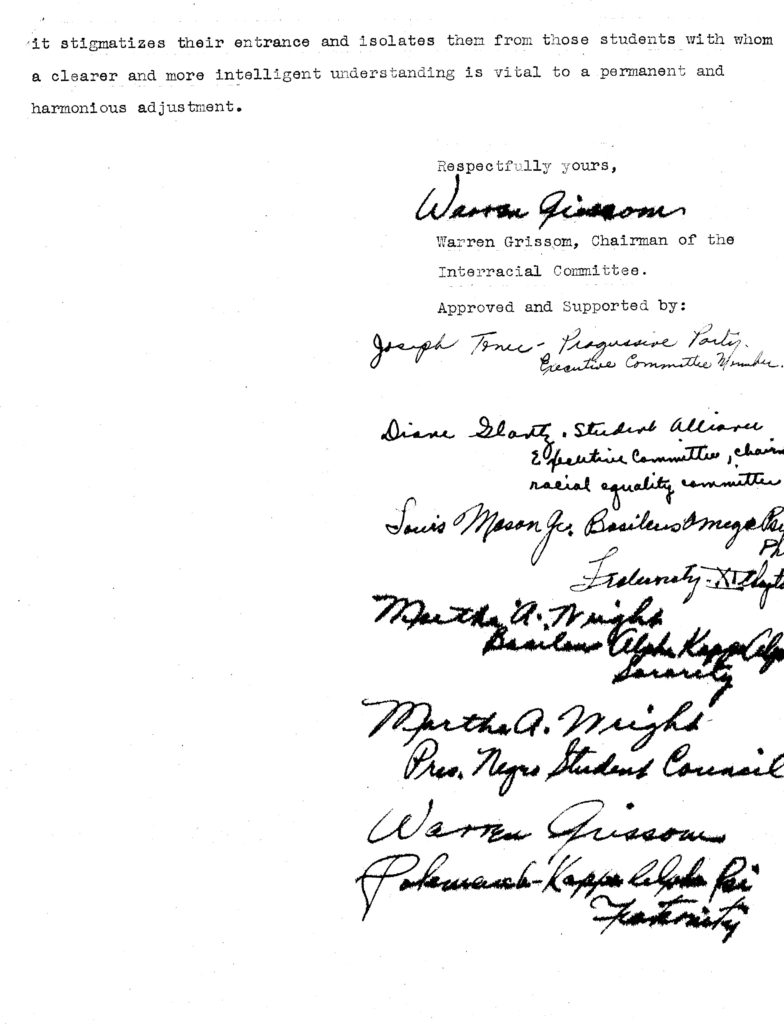

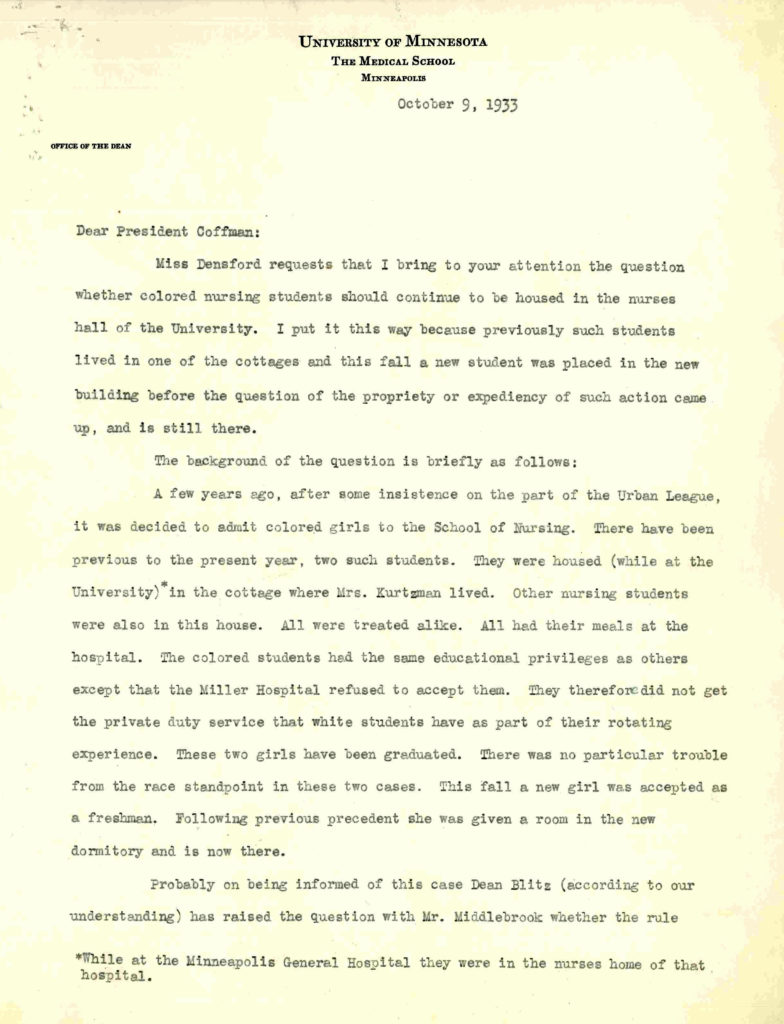

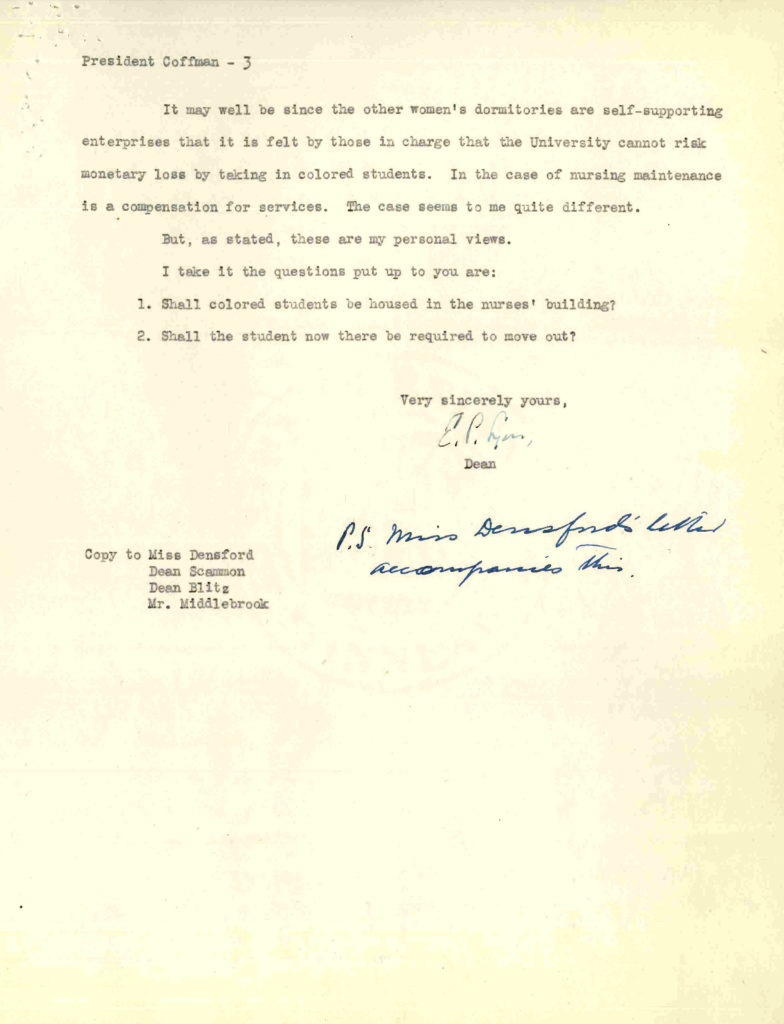

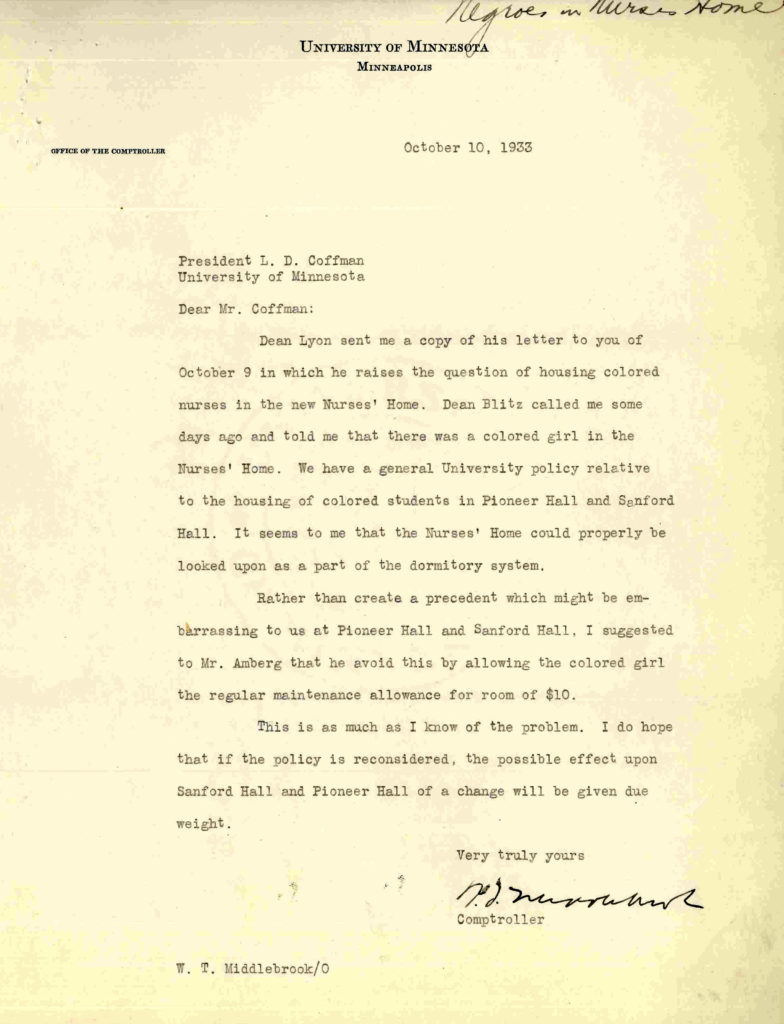

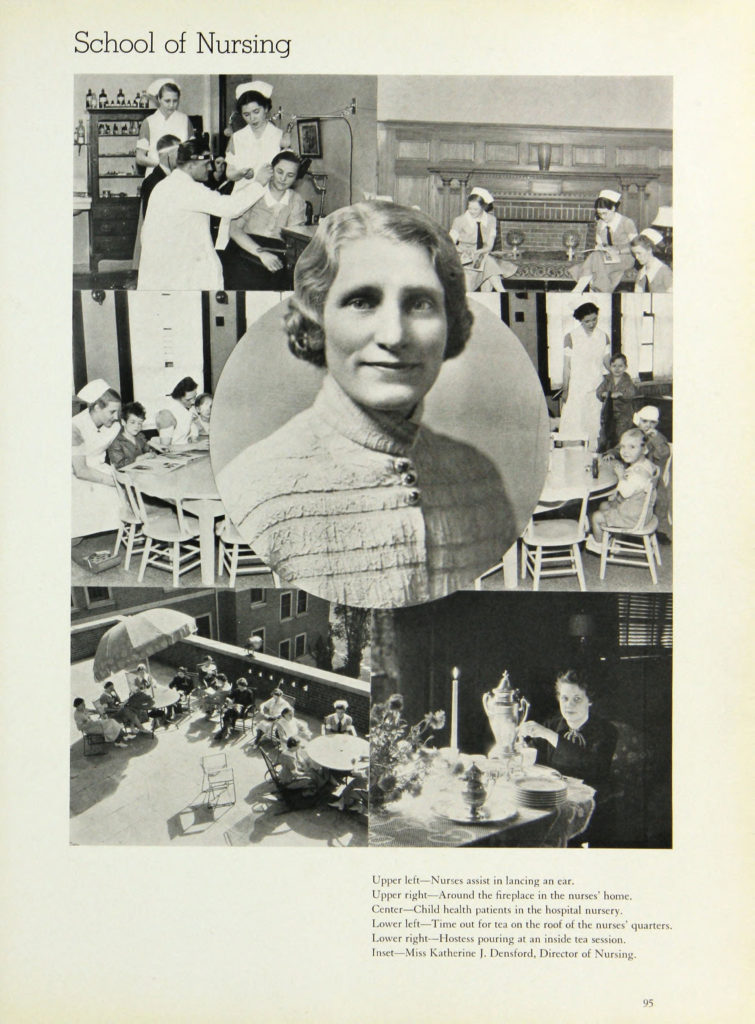

In 1933, Ahwna Fiti, the third African American woman admitted to the School of Nursing, attempted to move into the newly built Nurses Residence Hall (later Powell Hall), where all students were required to live. She was barred from moving into the dormitory by the key enforcers of segregated housing. They mobilized immediately to demand that Ms. Fiti find other housing. However, President Coffman then received competing opinions about the matter.

Elias P. Lyon (1867–1937), Dean of the Medical School, took exception to removing Ms. Fiti. He demanded that President Coffman respect the professionalism of the nursing program that required students to live together, and he reminded the president that as dean he had initially opposed integrating the School of Nursing; however, he could see no excuse for segregation if African American women were admitted to the nursing program.For a discussion of the integration of the School of Nursing see Ann Juergens, “Lena Olive Smith: A Civil Rights Pioneer,” William Mitchell Law Review 397 (2001): 433-435.

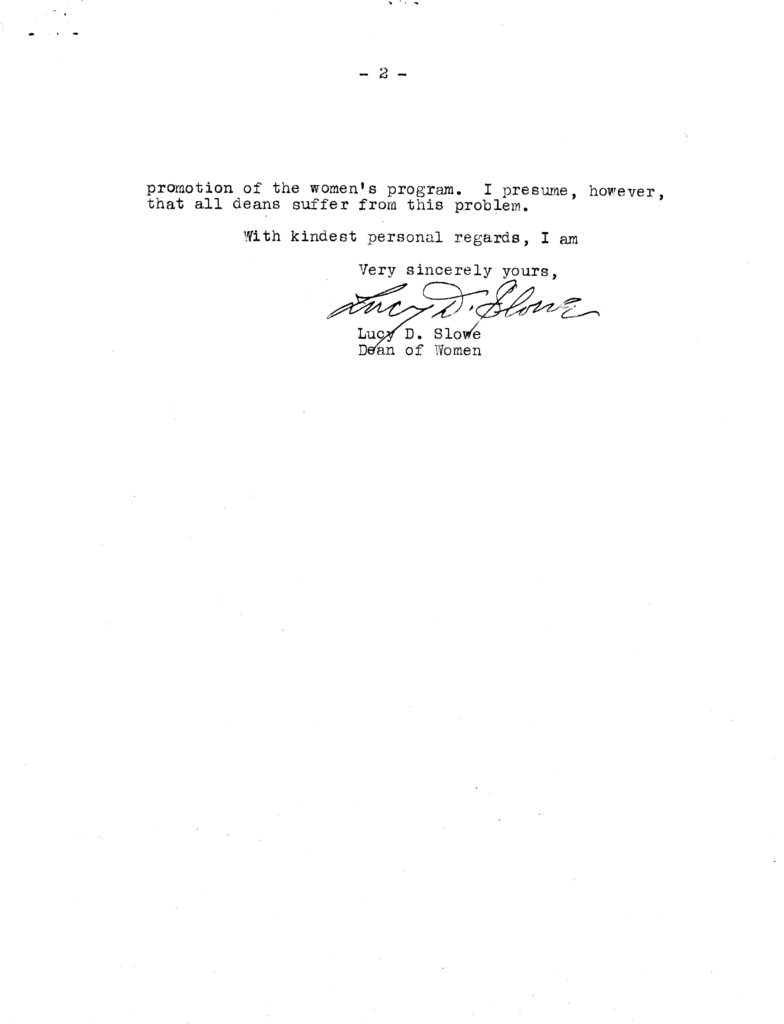

During the previous year, nursing students had lived together in a University cottage that was racially integrated. Now, Dean of Women Anne Blitz argued that nursing student housing had to be segregated.

President Coffman rejected Dean Lyon’s demand. Fiti was turned out of her home.

The University’s stance on segregated housing in the early 1930s mirrored a notorious example of white neighbors attempting to force out a young African American family that purchased a home in South Minneapolis. In 1931, Arthur Lee, a WWI veteran and postal worker and his wife Edith moved into their new home during the summer. They were confronted by mobs of white people, sometimes numbering 3,000, who threatened them and demanded that they leave. They were supported by civil rights attorney Lena Olive Smith, who just a few weeks later would write to President Coffman to protest his treatment of John Pinkett at Pioneer Hall.Greg Poferl, “The Arthur & Edith Lee Family Story,” East Side Freedom Library, Aug 24, 2020, https://eastsidefreedomlibrary.org/the-arthur-edith-lee-family-story/. For documentation of the history of restrictive housing covenants in Minneapolis and St. Paul that enforced segregated housing see “Mapping Prejudice: Visualizing the Hidden Histories of Race and Privilege in the Built Environment,” University of Minnesota, 2022, https://mappingprejudice.umn.edu/. For a digital series that examines the history of racial covenants in the Twin Cities and African American resistance see Jim Crow of the North, Twin Cities PBS, YouTube, Feb 25, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XWQfDbbQv9E&ab_channel=TwinCitiesPBS.

The Student Fight to Open the Doors, 1931-1935

Student groups at the University of Minnesota organized opposition to discrimination against African Americans at least as early as the 1920s. Activists drew on well-established traditions in the Twin Cities where African Americans were anything but passive in the face of racism. Their leadership was central through the social, religious, and defense organizations that they built.

Community groups such as settlement houses in Minneapolis and St. Paul played important roles in creating social, economic, and political networks. Similarly, NAACP chapters were established in St. Paul in 1913 and in Minneapolis in 1914 to combat discrimination. The Urban League, founded in the 1920s, focused very effectively on creating job opportunities for African Americans as well as taking on other forms of discrimination.

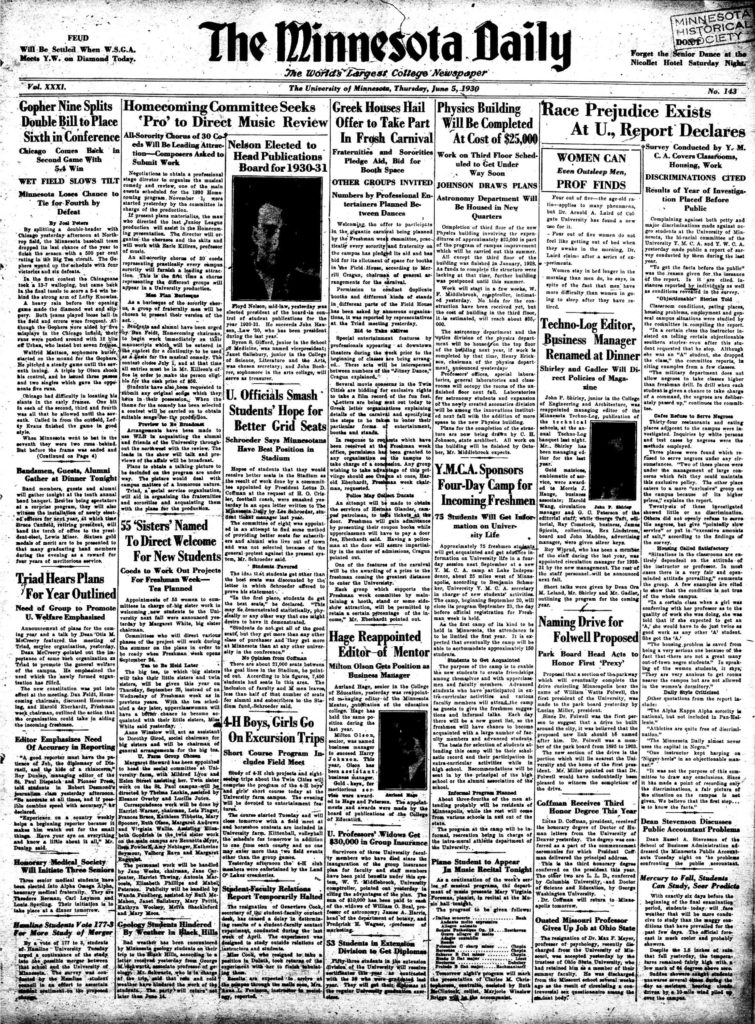

One of the first examples of the fight for African American student rights appeared in the Minnesota Daily in June 1930. The Biracial Committee of the campus YMCA and YWCA surveyed limitations faced by African American students. The Daily headline declared the existence of race prejudice, which they found in neighborhood restaurants that would not serve African Americans, the total lack of housing, and even classroom treatment by some professors. They called for change.

The expulsions of African American students from dormitories in the years that followed this report had a strong effect on students. Even before the Negro Student Council was founded in 1937, African American students challenged these policies, serving on committees of the All-University Council and the YMCA and YWCA.

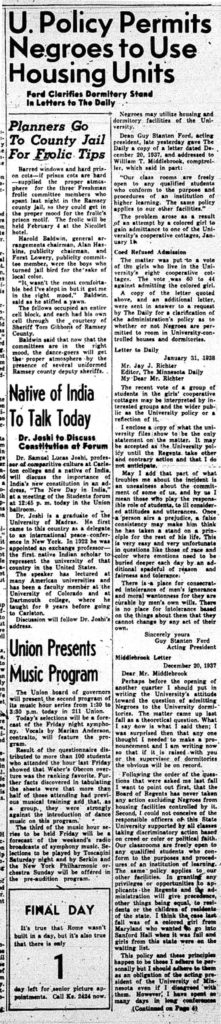

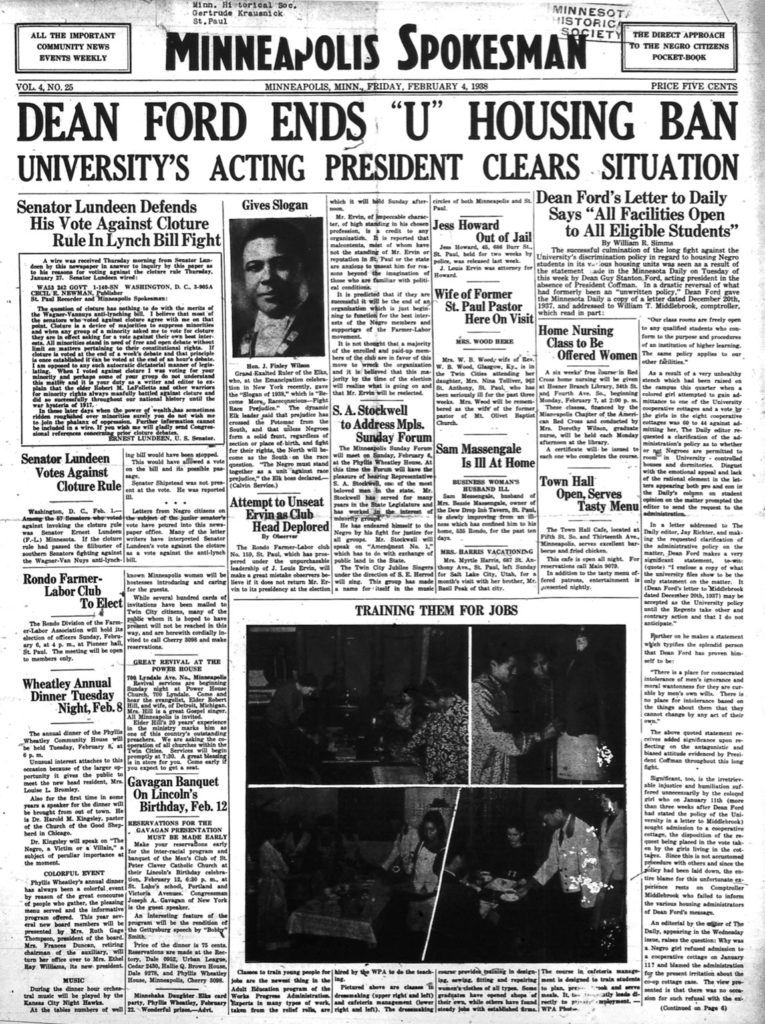

Students Officially Challenge President Coffman’s Policy on Segregated Student Housing, 1934-1935

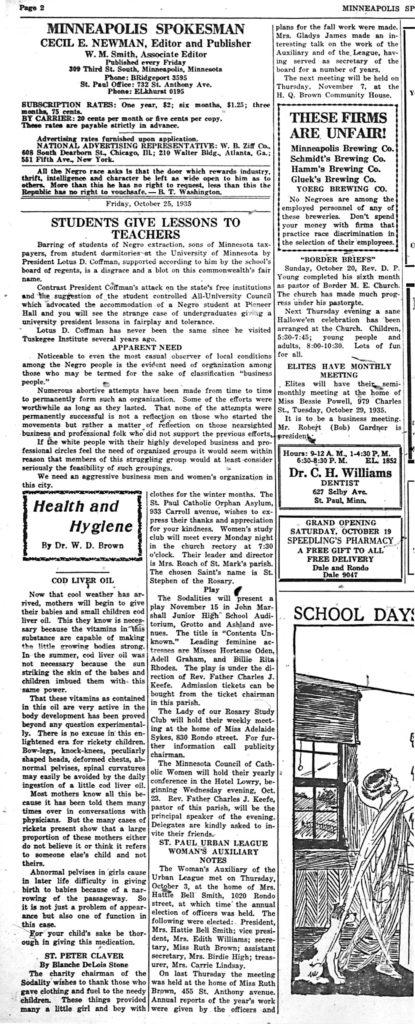

The Minneapolis Spokesman, the popular African American newspaper, reported on November 30, 1934, based on a Minnesota Daily story, that Lee Loevinger, the student chair of the Board of Publications, charged that the University would “not allow Negroes to live in Pioneer Hall.” He introduced a resolution at the regular meeting of the All-University Council on November 16, 1934, to end discrimination against marginalized groups. He called on the University to assure that “all citizens including those of all races, be admitted to the same official University privileges.” Dean of Student Affairs Edward Nicholson moved to “table the resolution.” Both men withdrew their measures and the “Council president was instructed to appoint a committee of three to investigate the charges.” Dean Nicholson’s move to block the resolution was consistent with the constant effort of administrators to stop integration.“Student Leader Hits ‘U’ Racial Discrimination,” Minneapolis Spokesman, Nov 30, 1934, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83025247/1934-11-30/ed-1/.

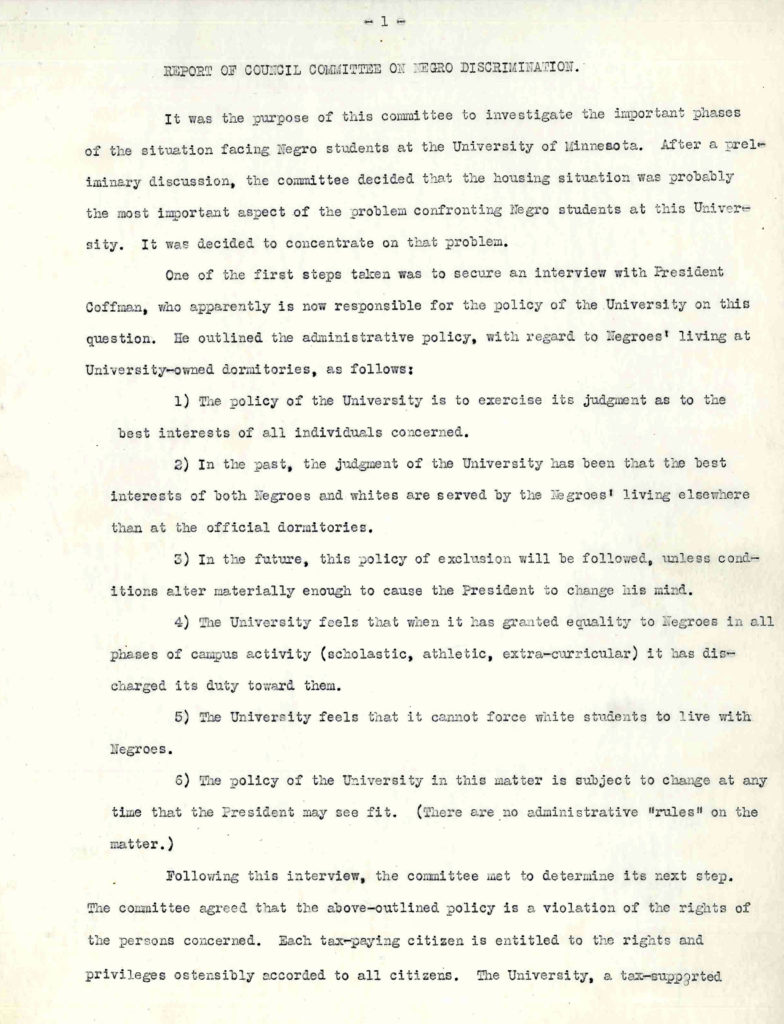

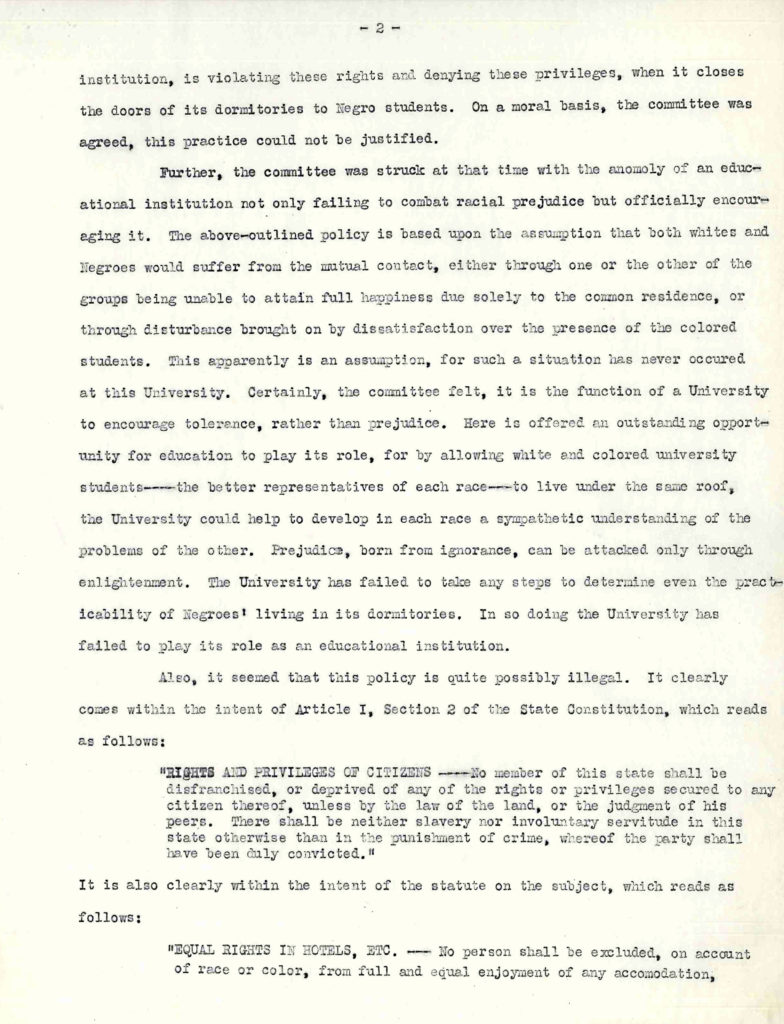

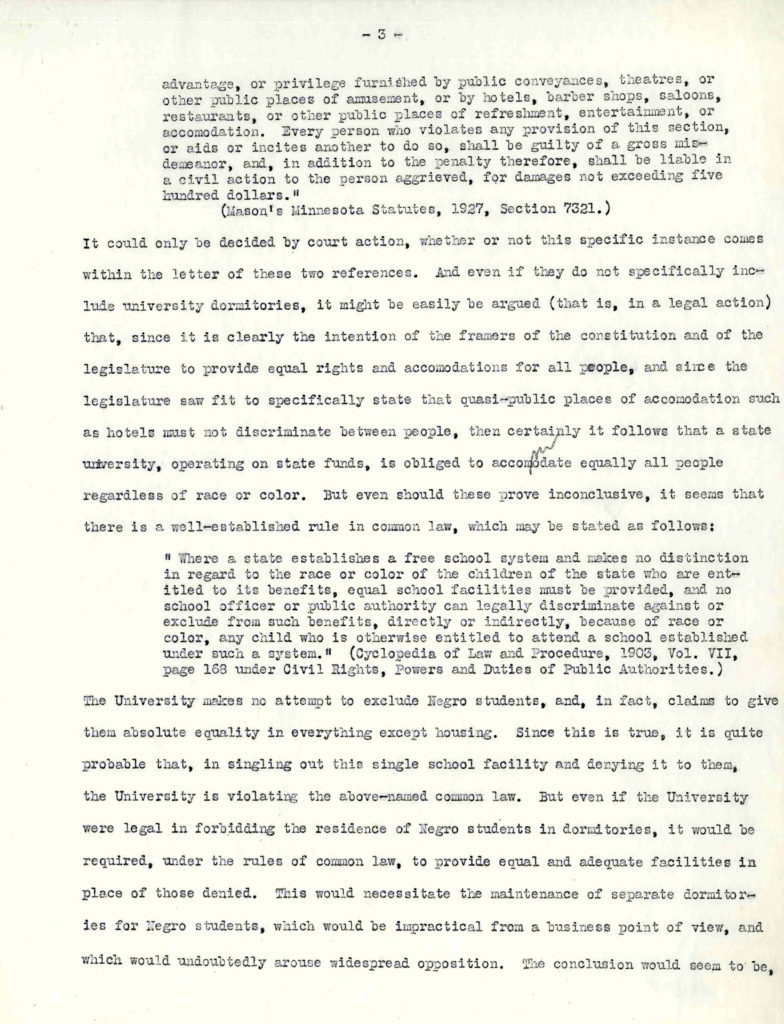

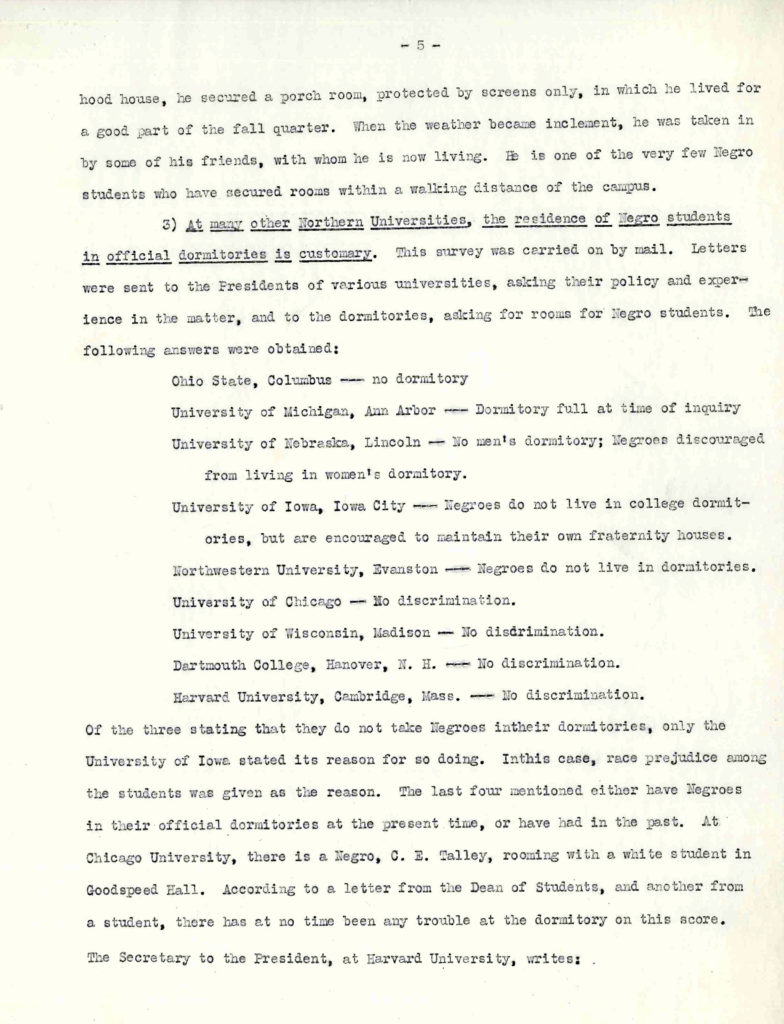

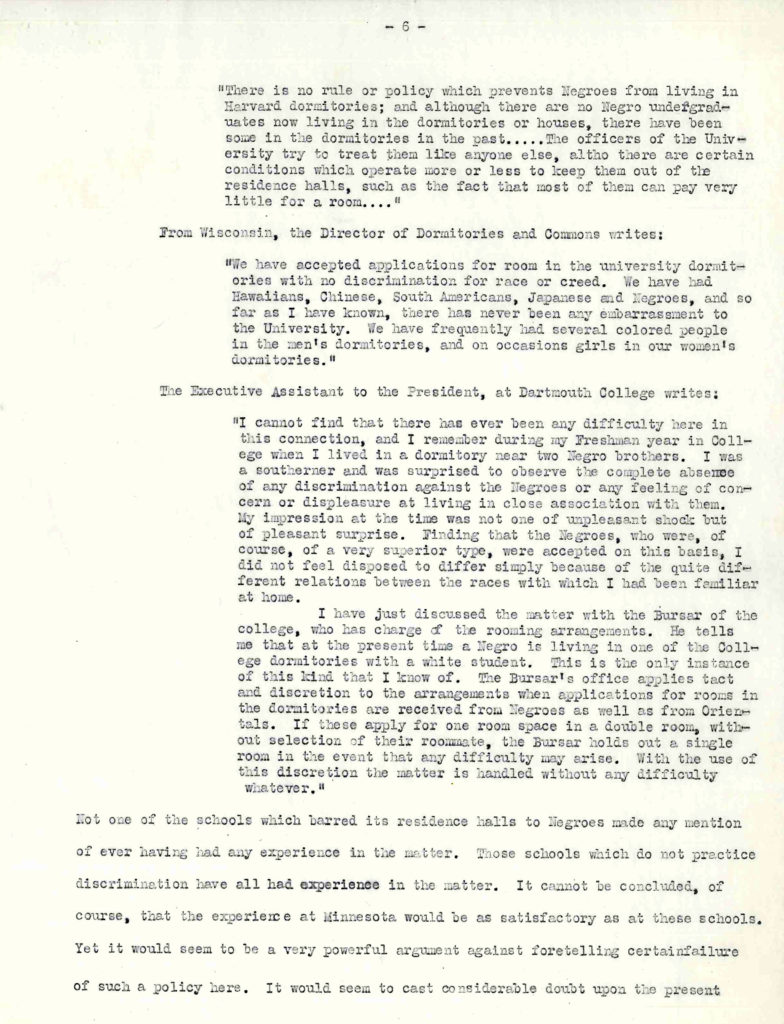

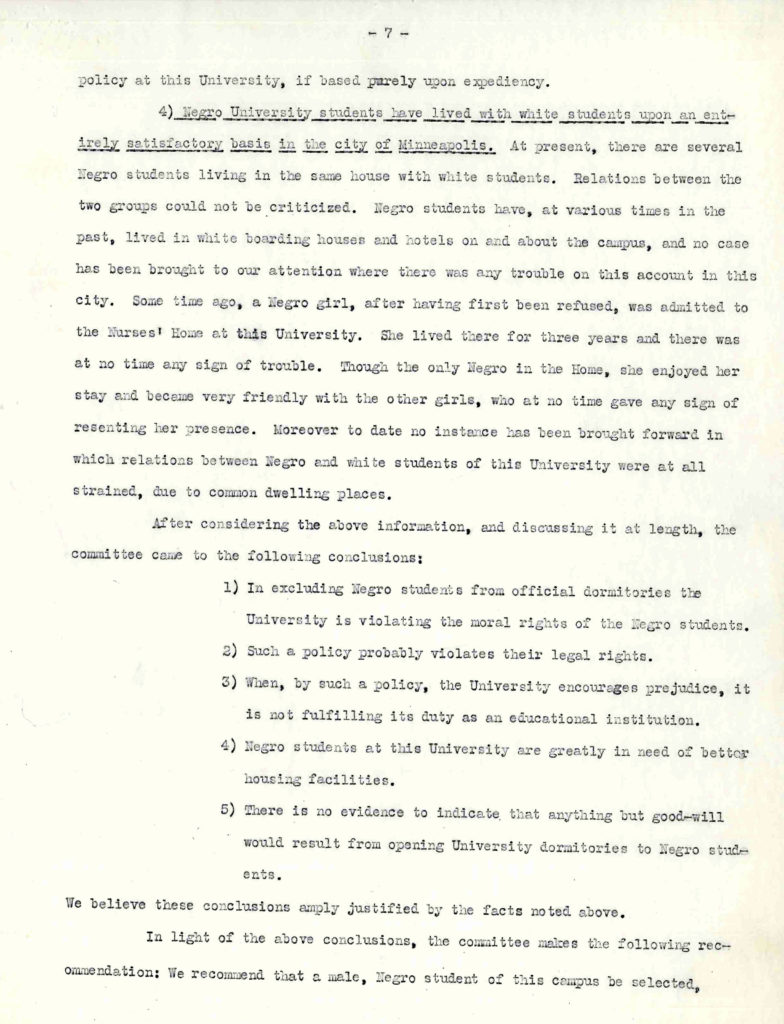

Six months later, in May of 1935, the All-University Council Committee on Negro Discrimination submitted its report. The committee was chaired by Howard Kahn, a progressive white Jewish student, and included Arnold Walker, an African American graduate student and leader, and Robert Loevinger, also a progressive white Jewish student. The report requested that one African American student be admitted to Pioneer Hall as a resident. The request was supported by eight carefully argued pages which laid out the legal, educational, and moral rationales for equality in housing for African American students. The report cited Minnesota statutes and common law that outlawed both inequality in education and the failure to provide accommodations for students from marginalized groups. It described the experiences of other universities that were queried by the committee members about racially integrated dormitories. The committee reported on the experiences of the University of Chicago, University of Wisconsin, and Dartmouth College, where no problems resulted from racially integrated dormitories. In fact, the report called on the University of Minnesota to take moral leadership to foster mutual understanding of one another for the good of both groups.

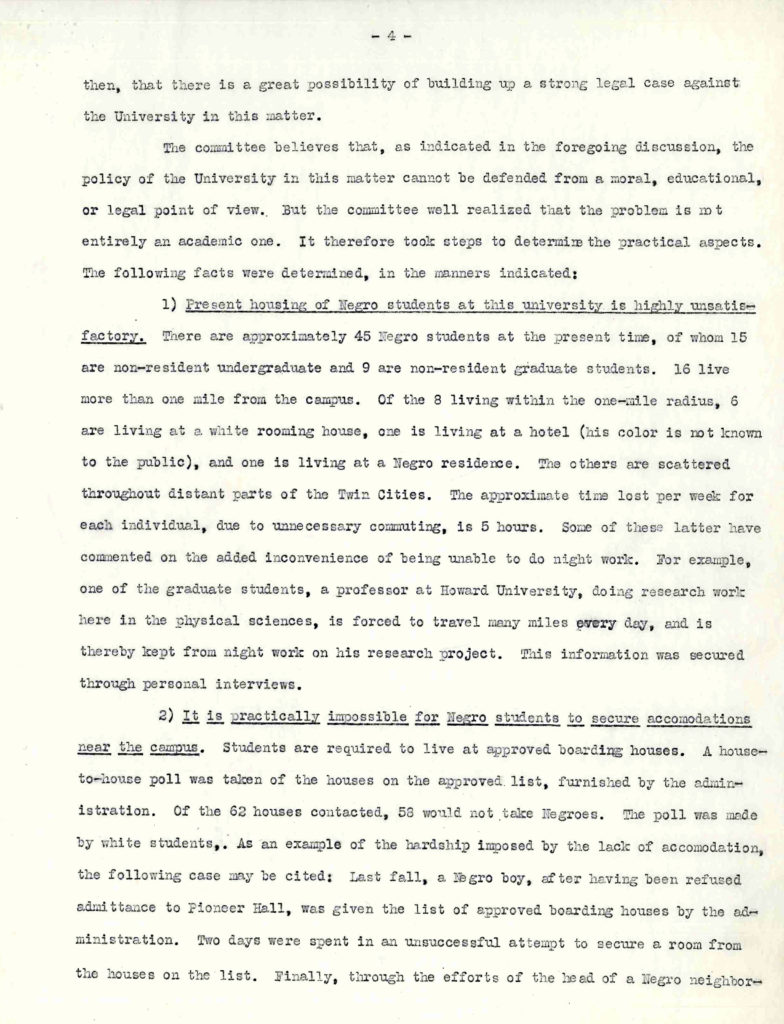

The report also detailed the harm to African American students with no access to on-campus housing. The authors surveyed the 24 non-resident undergraduate and graduate students of the 49 enrolled African American students. Most of these students lived well beyond the campus neighborhood, requiring lengthy commutes, which often made it impossible for them to work in the evenings. The report authors also took a house-by-house poll of the 62 University-approved boarding houses available to students. Fifty-eight of these residences would not accept African Americans.

Kahn, Walker, and Loevinger noted in their report that they met with President Coffman before they began their research to learn his view of segregated housing and how to change this policy. President Coffman informed them that “the best interests of both Negro and whites are served by Negroes’ residing elsewhere than at the official dormitories.” Coffman also explained that change would only occur if “conditions alter materially enough to cause the President to change his mind.” Coffman further insisted that “the University cannot force white students to live with Negroes.” Finally, they were informed by President Coffman that“the policy of the University is subject to change at any time the President may see fit. There are no administrative rules on the matter.” President Coffman clearly and unambiguously situated his power and authority in the decision to segregate student housing.

President Coffman Firmly Established Racially Segregated Housing in 1935 as an Accepted Norm of University of Minnesota Life with the Support of the Board of Regents

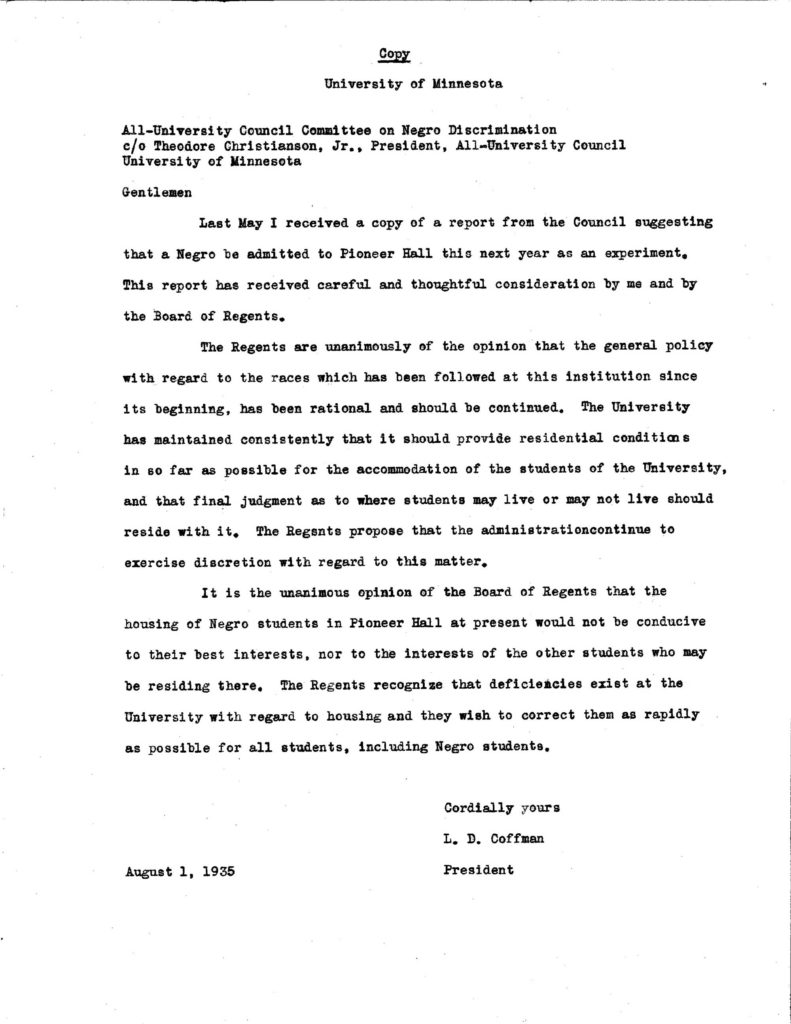

Lotus Coffman formalized his four-year campaign to segregate taxpayer-funded student housing with exclusively white residents in response to the first organized student response to that segregation. The All-University Council called on President Coffman to integrate Pioneer Hall in 1935. For the first time, the President requested that the Board of Regents support his policy, and its members voted unanimously to do so at their meeting on July 31, 1935. They affirmed two of Coffman’s central ideas. The first was that the “administration exercised discretion and final judgement as to where students should reside.” The second was that “the housing of Negro students at Pioneer Hall would not be conducive to their best interests nor the interests of other students residing there.”Board of Regents Meeting Minutes, July 1, 1935, University of Minnesota, University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy, https://hdl.handle.net/11299/45471.

President Coffman wrote to the student government in August 1935 to inform its president, Theodore Christianson, of the decision. The letter provided the prevailing rationale for denying all African American students the right to live in university housing until 1938 when Acting President Guy Stanton Ford changed the policy.

President Coffman asserted that segregated housing was essential to the University of Minnesota and did not constitute discrimination. Coffman not only claimed that racially segregated housing served both white and African American students best—he insisted that only white students were entitled to live in campus housing paid for by Minnesota taxpayers.

President Coffman Secretly Plans for Racially Segregated Housing

Lotus Coffman’s response to the All-University Council Committee on Negro Discrimination report included his admission that there was a problem, and that was the lack of adequate housing for some students. Coffman asserted that the Regents hoped to address the deficiency as quickly as possible, “including for Negro students.”

African Americans in the Twin Cities monitored what happened on the campus through the press. The Minneapolis Spokesman editorialized that the University and President Coffman needed to learn lessons in fair play and tolerance from students. The article termed the decision by President Coffman and the Board of Regents to maintain segregation as a “disgrace and a blot on this commonwealth’s fair name.” The concluding line of the article noted that “Lotus D. Coffman was never the same since visiting Tuskegee Institute several years ago.” It was a prescient observation as Mr. Coffman was already formulating a plan for segregated men’s dormitories.

The Committee on Negro Discrimination’s case for the University’s legal responsibility to provide accommodations for African American students was clearly not lost on the President or the Board of Regents. Without making explicit what type of housing he had in mind for African American students in 1935, several documents in the archive reveal how his plan began to take shape.

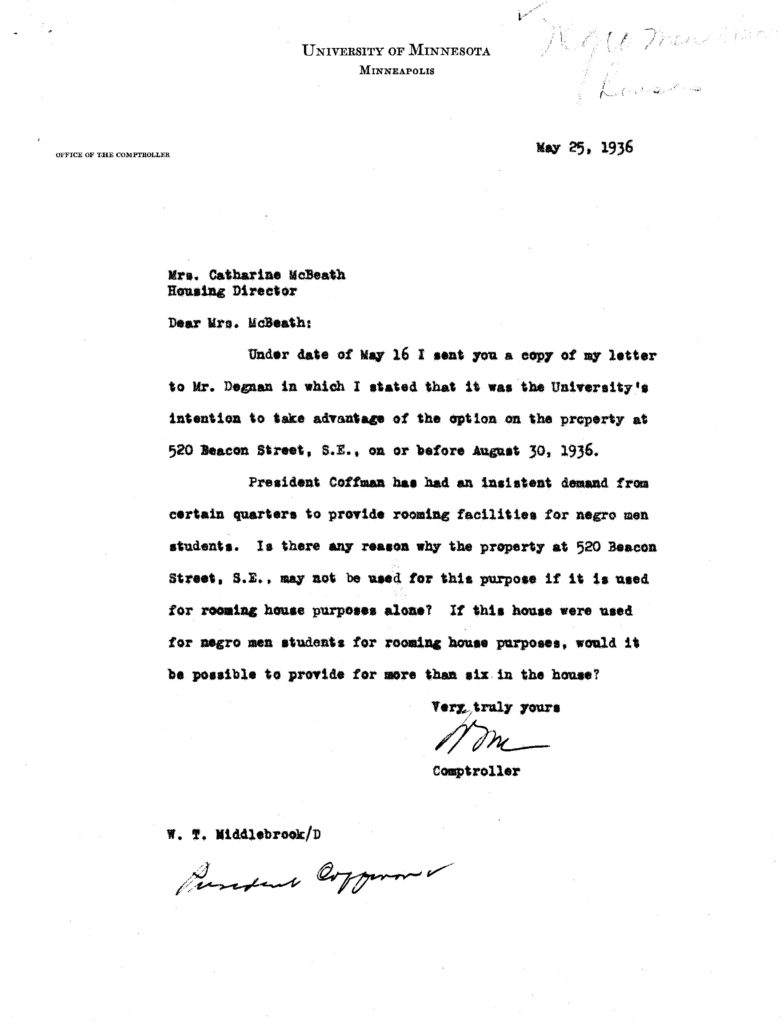

University Comptroller William Middlebrook, who was one of the key enforcers of segregated housing on campus, pursued an option for housing for “negro men students” (uncapitalized in the original) with Housing Director Catherine McBeath. Middlebrook characterized the need for housing for African American students as an “insistent demand from certain quarters,” rather than simply the need for student housing. Middlebrook and Coffman sought to turn an available building near campus into “housing for six negro men.” While other Big Ten universities at that time excluded African Americans from dormitories or had no student housing, only southern universities enforced racial segregation as the ideal solution. Coffman’s dream of segregated housing for African American students would be realized and immediately challenged in 1942, several years after his death.Discussion of the history of President Coffman’s ideas for using an “International House” for segregated housing for African American men appears in University of Minnesota, Report on the Taskforce for Building Names and Institutional History, February 25, 2019, 22-24.

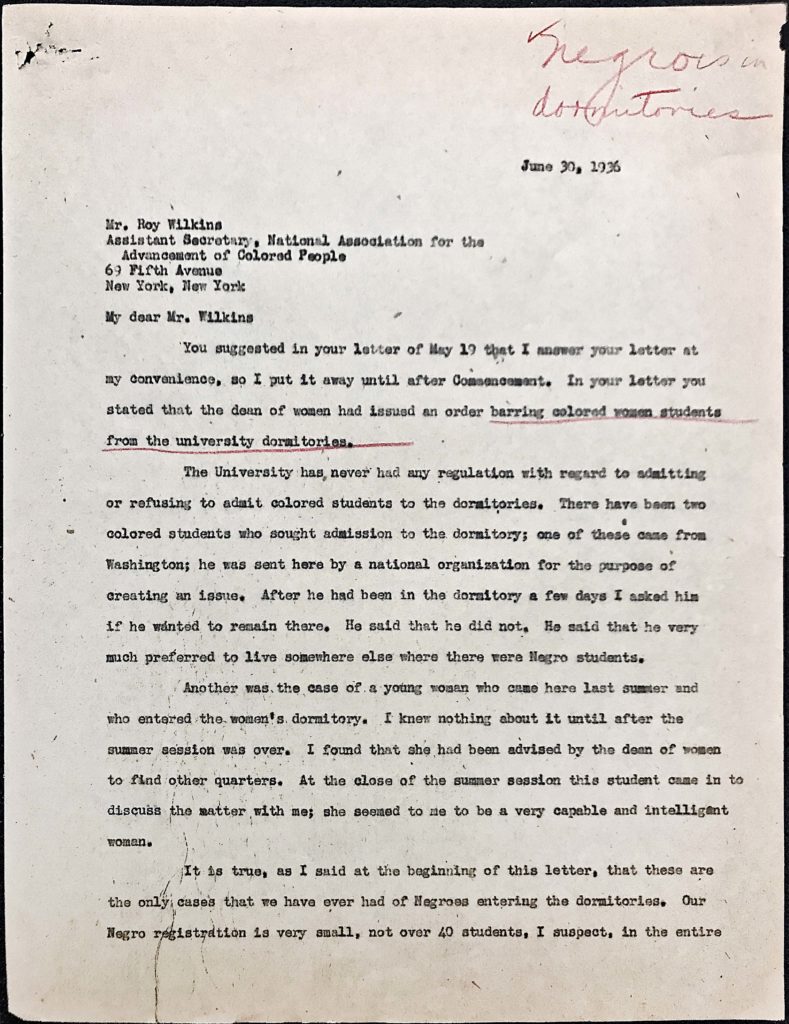

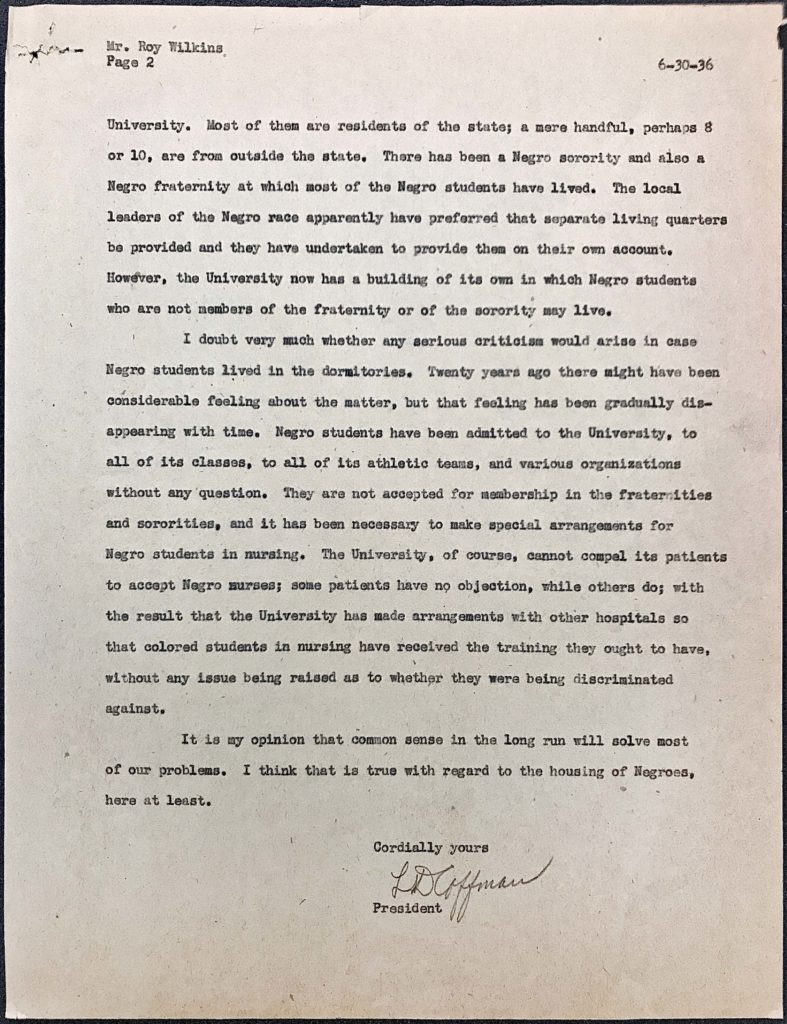

President Coffman alluded to this plan for segregated housing again in a letter to Roy Wilkins (1901-1981), one of the University’s most important alumni. Wilkins would ultimately head the national NAACP and was an American Civil Rights leader for more than fifty years. Mr. Wilkins wrote to President Coffman in 1936 to express his shock that African Americans were being excluded from dormitories.

Coffman’s response was repeatedly dishonest, particularly when he wrote that “the local leaders of the Negro race apparently have preferred that separate living quarters be provided, and they have undertaken to provide them on their own account.” He added, “However, the University now has a building of its own in which Negro students who are not members of the fraternity or sorority may live.”

The NAACP’s opposition to segregating Pioneer Hall, protests in the African American press, and the 1935 demand for integrating the dormitory all reveal Coffman’s lie about African American support for segregation. However, his claim that a building existed where African American students may live likely references the correspondence with Mrs. McBeath. But the property on Beacon Street S.E. provided no such housing when this letter was written or thereafter. That Coffman also insisted to Mr. Wilkins that no policy existed barring integrated dorms and that he believed no problem would exist if they were integrated was precisely the opposite of every stand he had taken and continued to take until his death.

Excluding African American Women Students from Campus Housing, 1936-1937

With Lotus Coffman’s plan firmly in place for white-only dormitories, exclusion of African American students persisted. Young African Americans from out-of-state and outside the Twin Cities found themselves barred from moving into another form of student housing, cooperative cottages.

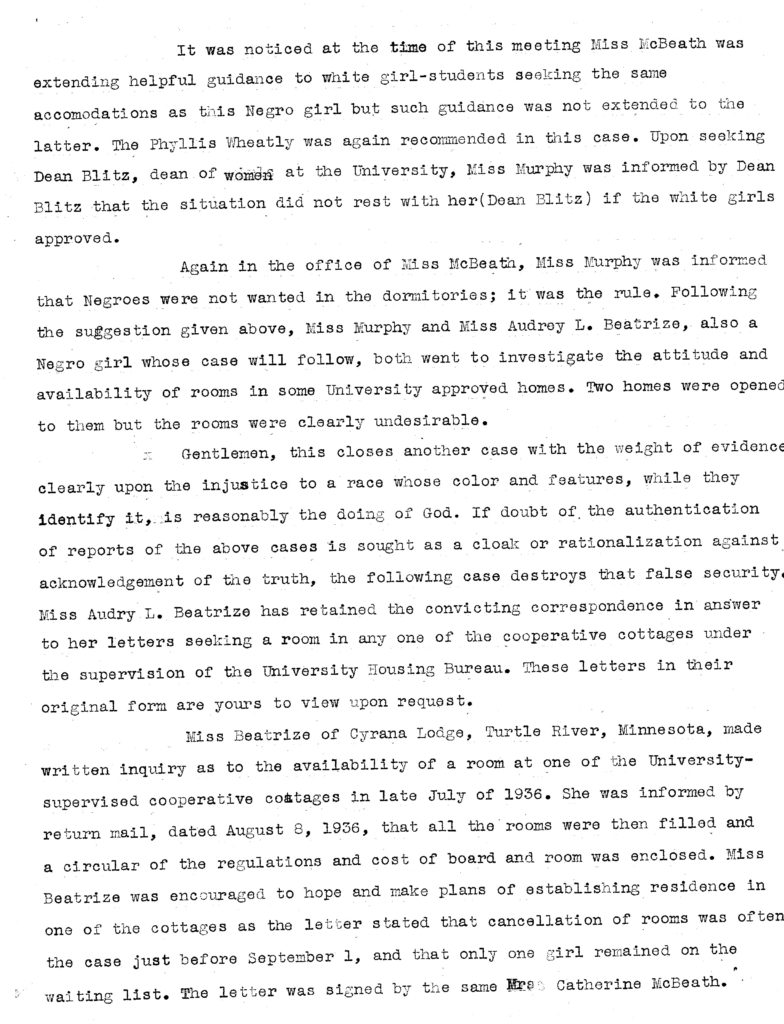

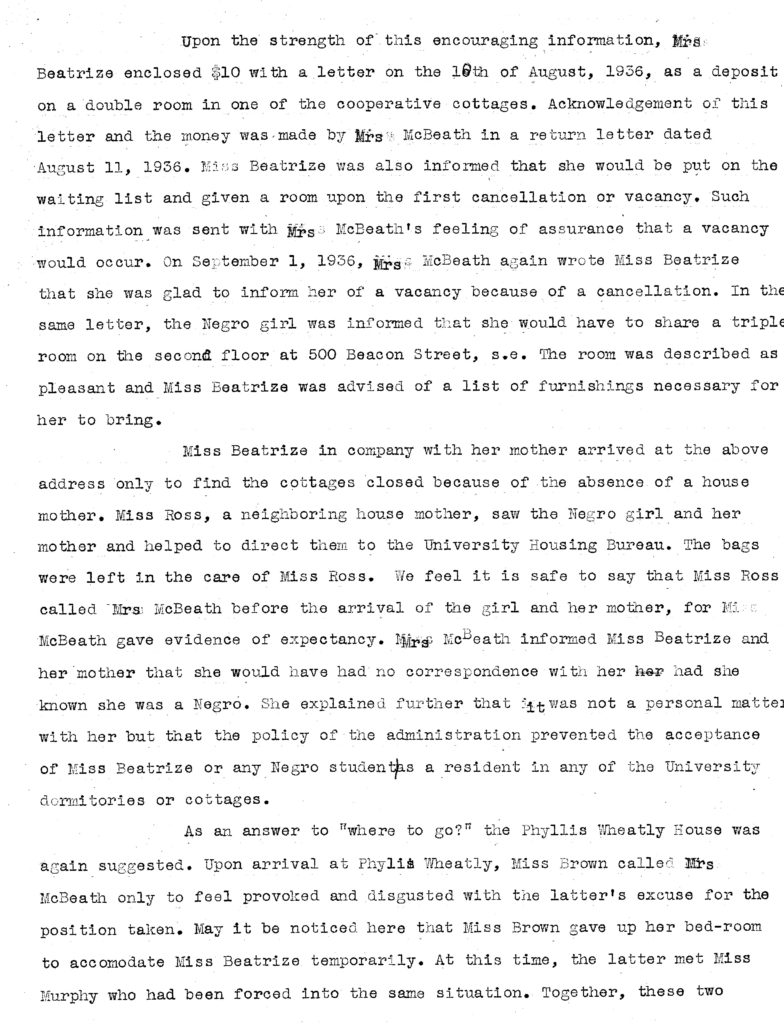

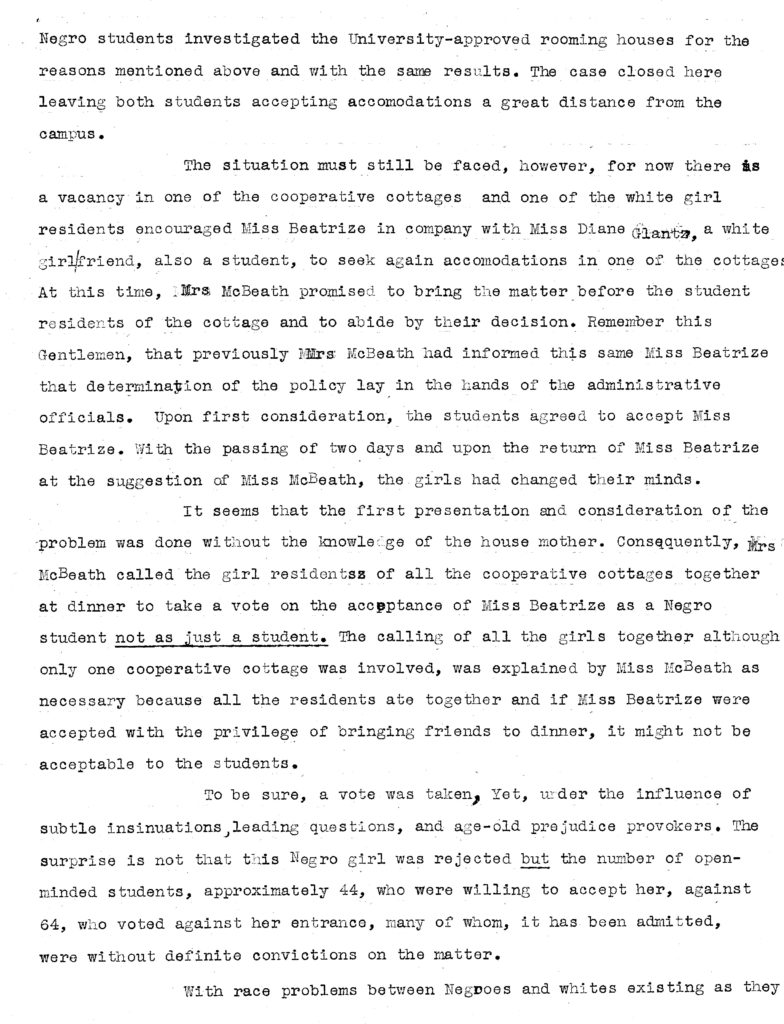

In 1936, incoming students Audrey L. Beatrize of Cyrana Lodge, Turtle River, Minnesota and Elizabeth Murphy of Baltimore, Maryland looked forward to their first homes at the University in the cooperative cottages located on Beacon Street on the East Bank of the campus. They planned to join other women students in sharing meals, some cooking responsibilities, and common spaces.

When Housing Director Catherine McBeath learned that these young women, accompanied by their mothers, were African Americans, she informed them that they had to find other housing because of “University policy.” She had the full support of Dean of Women Anne Blitz, who vigorously supported segregated student housing. Once again, Gertrude Brown was contacted at Phyllis Wheatley House to find these students housing away from campus with African American families.

Dean Anne Blitz as an Enforcer of Segregated Housing

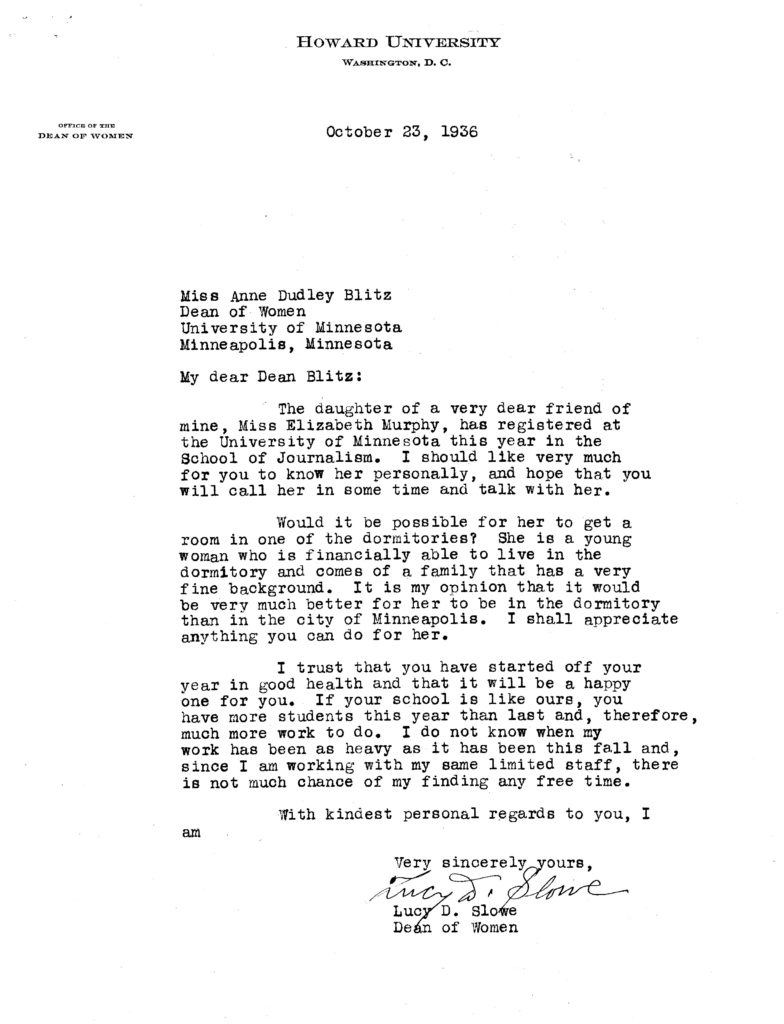

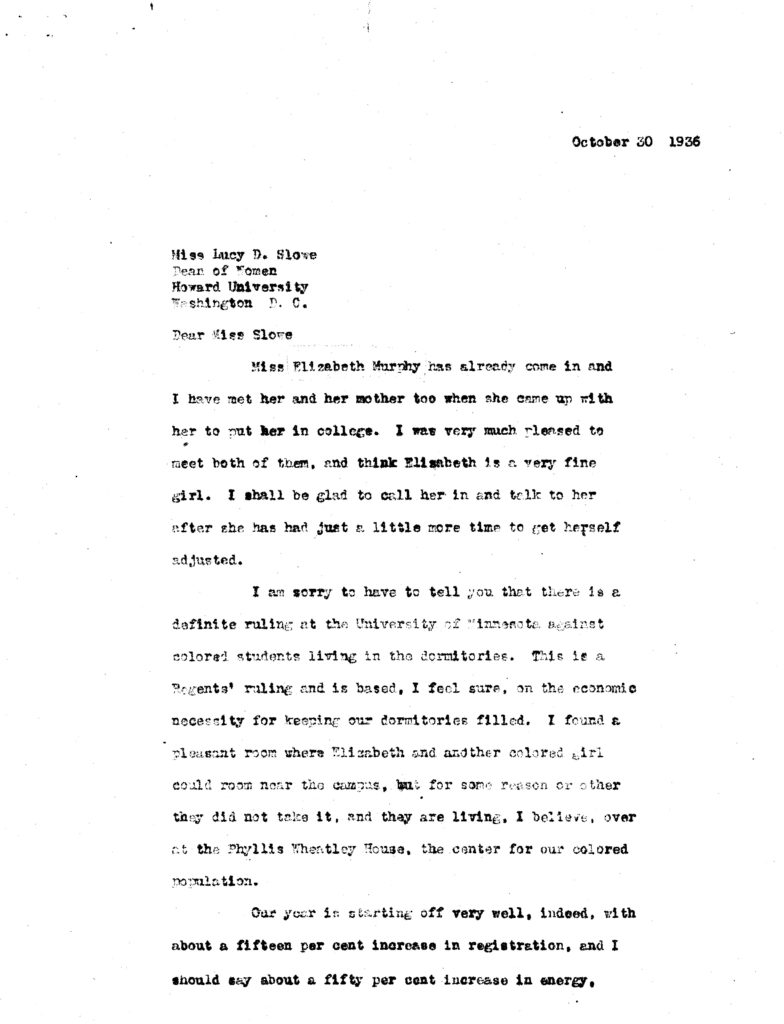

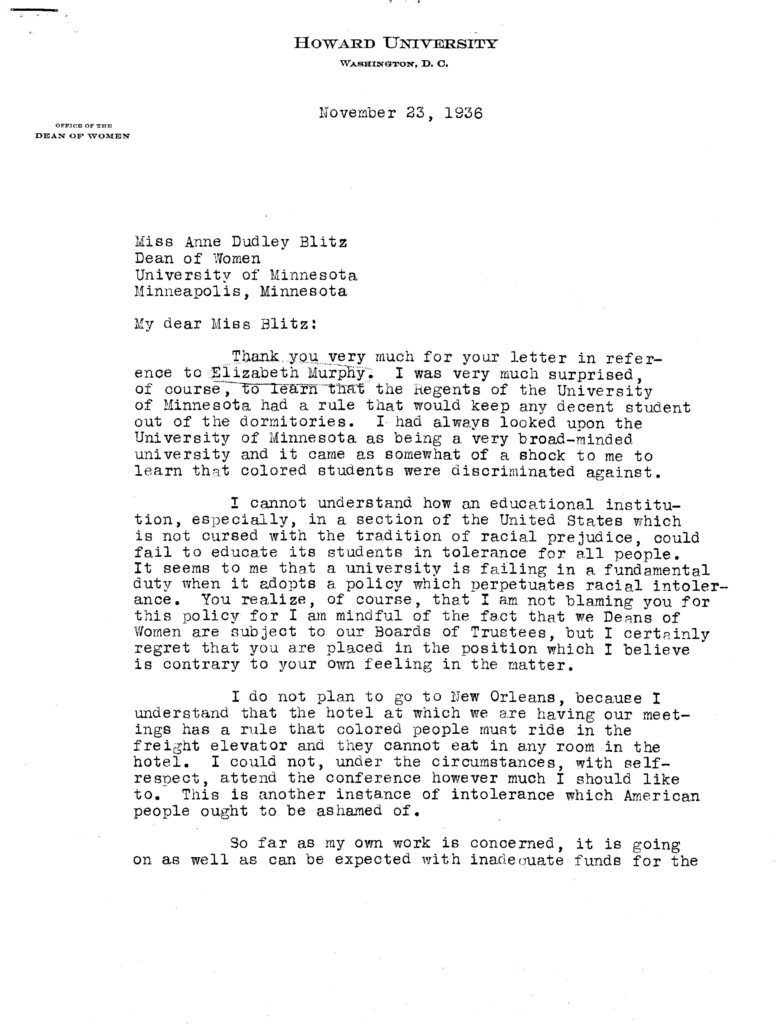

Dean Blitz’s zeal for segregation was striking. Shortly after Elizabeth Murphy and her mother were notified that there was no “home” for Elizabeth at the University of Minnesota, Blitz received a letter from the Dean of Women at Howard University Lucy Diggs Slowe. Howard University is a historically Black college and was segregated when she wrote to Dean Blitz to ask her to be certain to look after Elizabeth, the daughter of a very close friend.

This correspondence between Dean Anne Blitz of the University of Minnesota and Dean Lucy Slowe of Howard University was one more occasion for Dean Blitz to reiterate the University of Minnesota’s commitment to segregated housing. Further, Dean Blitz insisted that housing segregation was an economic necessity, which revealed the administration’s fear that white students would not live in a dormitory that was racially integrated.

When Dean Blitz genially wondered in her response if Dean Slowe would attend their next gathering of Deans of Women in New Orleans, Dean Slowe had to point out to her that she would not be allowed on an elevator in the hotel where they were gathering because she was an African American. Slowe declined to attend.

These three letters reveal the very different assumptions held by these two Deans of Women. African American Lucy Slowe was shocked that the University of Minnesota, a northern university, would create segregated housing. Dean Blitz assumed, without embarrassment, that the races should be segregated in the United States, whether it is in a dormitory or a hotel.

African American Students and their Allies Expand the Fight for Housing, and Realize their First Victory, 1937-1938

The more President Coffman, his staff, and those who oversaw housing insisted on segregation, the more effectively and tirelessly African American students and their allies fought to defeat them.

In November of 1936, African American students founded the Negro Student Council (also called the Council of Negro Students), according to a Minneapolis Spokesman article published on December 4, 1936. The newspaper reported that 35 students attended the second meeting which was held in University of Minnesota Union. Arnold Walker, who was initially a temporary chair, announced that the group had been recognized by Dean Nicholson, Dean McCleery, and Dean Blitz from Student Affairs after meeting with students Walker, Nellie Dodson and John Brooks. They selected students to form committees that included Housing, Discrimination, Student Alliance, and Forum Groups. Their Discrimination Committee was to meet with leaders in the African American community, which included the Urban League, the Wheatley House, and St. Paul’s Hallie Q. Brown Community House. Like most other student organizations of the era the group also anticipated committees for Dad’s Day and Homecoming. The nearly 20 students listed in the report on the Negro Student Council is one of the best and only sources for finding the names of African Americans attending the University of Minnesota. Their names appear in the article.

The Negro Student Council became a crucial political organization whose members led the fight to open the dormitories to all students regardless of race. It also provided support and connection for all African American students. Arnold Walker, the first president of the Council of Negro Students, served on the committee of the All-University Council that proposed integrating Pioneer Hall. He was followed as president by Martha Wright, who also served on the Interracial Committee, which presented a report to Local 44 of the American Federation of Teachers in 1937.

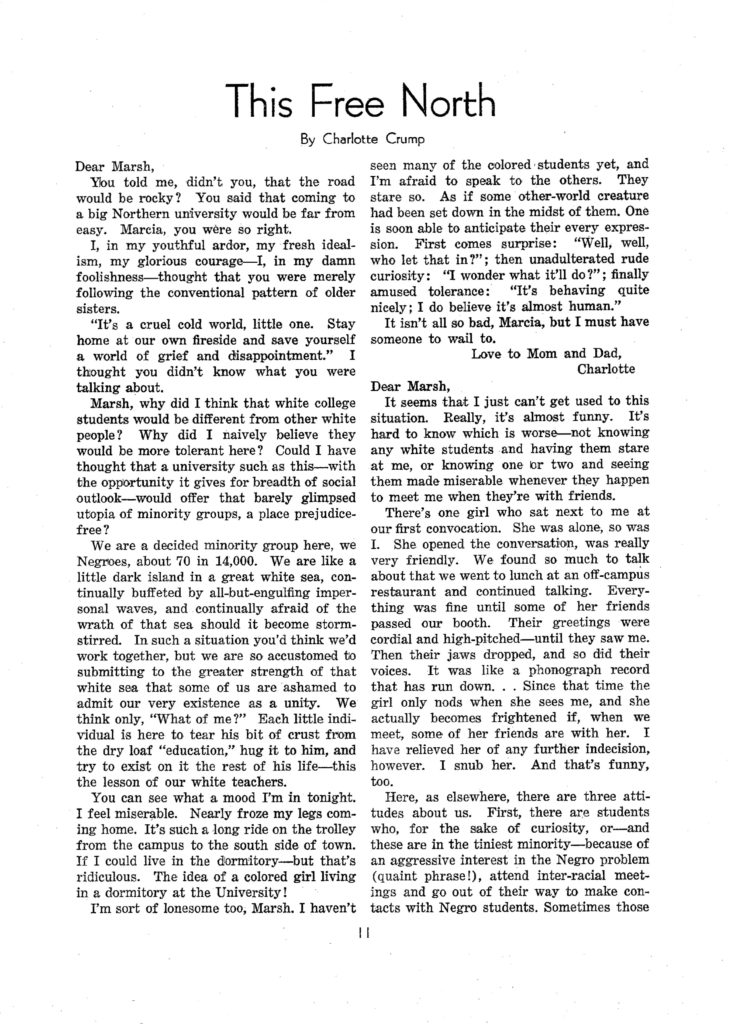

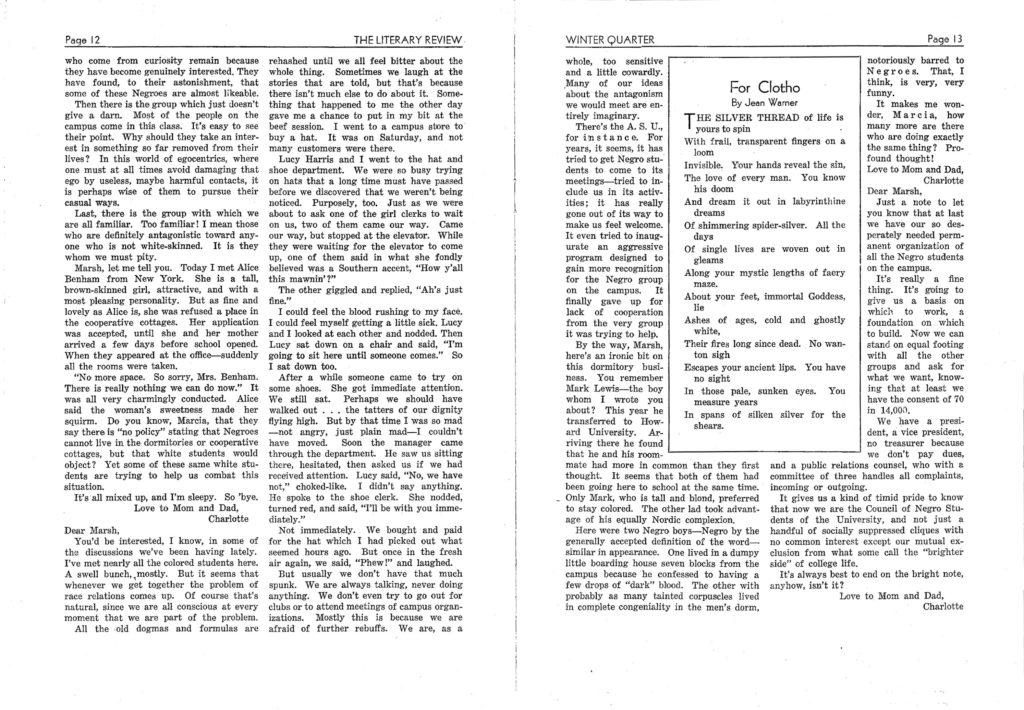

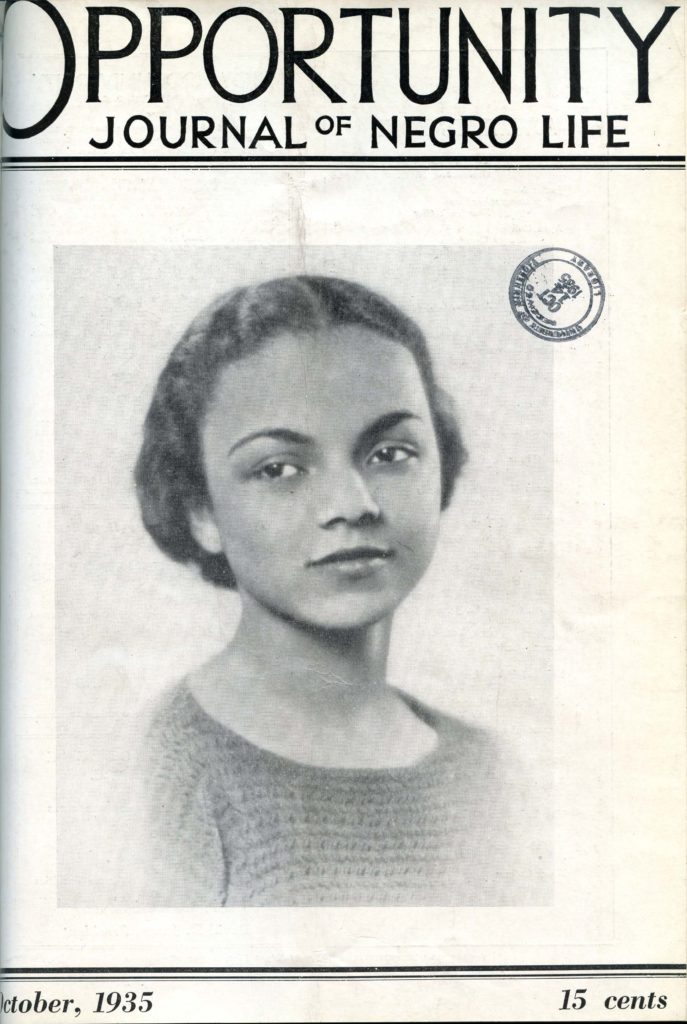

One of the only accounts of the Council of Negro Students appeared in a semi-fictional story in the University Literary Review in 1937. Charlotte Crump was an undergraduate at the University of Minnesota from 1935-1939. She studied to be a journalist, was active in campus politics, and was a founder of the Council of Negro Students. In the Literary Review, a supplement of the Minnesota Daily, Ms. Crump wrote, in the form of a series of letters to her older sister, an account of her experiences as an African American student “at a big Northern University.” In “This Free North,” her story, she described in detail how she and other African American students felt marginalized by the “ocean” of white students. She relayed how she was treated at a campus area clothing store where she and a friend could not get a salesperson to wait on them, their long wait simply to pay for what she bought, and how salespeople ridiculed them. She also described the near impossibility of African American students finding on-campus housing, as well as her long commute to the only housing available to her. She concluded her story with the formation of the Negro Student Council (which actually happened in 1936). She wrote to her sister,

“At last we have our so desperately needed permanent organization of all the Negro students on the campus.

It’s really a fine thing. It’s going to give us a basis on which to work, a foundation on which to build. Now we can stand on equal footing with all the other groups and ask for what we want knowing that at least we have the consent of 70 in 14,000.

It gives us a kind of timid pride to know that now we are the Council of Negro Students of the University, and not just a handful of socially suppressed cliques with no common interests except our mutual exclusion from what some call ‘the brighter side’ of college life.”“This Free North” was subsequently published in the magazine of the Urban League: Charlotte Crump, Opportunity: Journal of Negro Life, vol 15 (September 1937), 271-272, 285.

The appearance of “This Free North” led Dean of Women Blitz to ask Charlotte Crump to meet with her. In her request to meet, Blitz complained that Ms. Crump had not discussed matters with her in advance so that she would avoid “misstatements” in her story.

There is no record of whether they met. Crump’s story was remarkably accurate about housing according to all other sources. Blitz was clearly unnerved by an African American student explaining what happened when her friends were not allowed to move into campus cottages to which they had been admitted.

Arnold Walker also coordinated the efforts of the Negro Student Council to integrate taxpayer-funded student housing with the African American communities of St. Paul and Minneapolis. The 1937 Minneapolis Spokesman article directly below quotes Walker’s call to mobilize citizens to write to Governor Elmer Benson and elected officials about the appointment of members of the Board of Regents. Recalling that in 1935 the Regents had supported segregation, the strategy involved lobbying legislators, who elected the regents, to support integration.

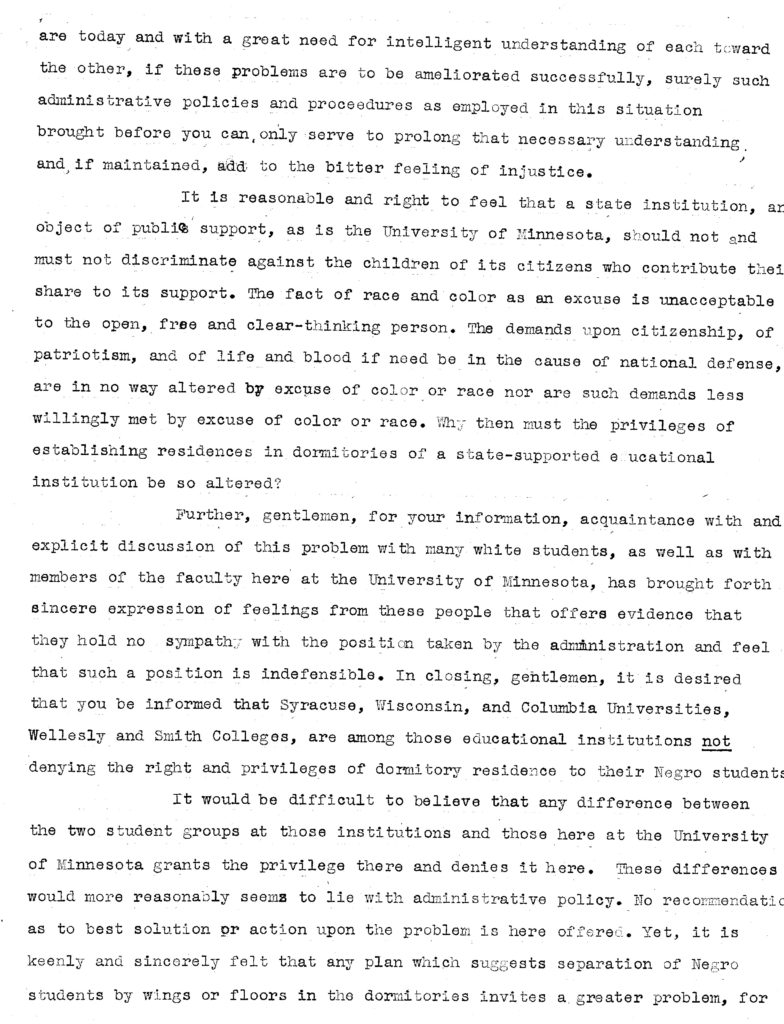

The Council of Negro Students also formed important relationships with other student groups and members of the University faculty who were committed to stopping racial segregation in student housing. These political alliances are revealed in a January 21, 1938 memorandum on the “housing situation” for African American students written by undergraduate Warren Grissom and other students at the request of Professor Benjamin Lippincott, a distinguished member of the Department of Political Science. Lippincott chaired Local 44 of the American Federation of Teachers, which was a union-like organization for university faculty. The student signers of the memorandum list their affiliations as the “Interracial Committee,” “Racial Equality Committee,” “Progressive Party,” “Negro Student Council,” and the local chapters of the national African American Greek-letter men’s fraternity (Alpha Phi Alpha) and women’s Greek-letter sorority (Alpha Kappa Alpha).

Not only does the memorandum (also included earlier in this essay) provide information about the experiences of African American students and housing which appears in few other written sources, it also reveals the growing numbers of groups and interested constituents committed to bringing about change. These documents counter the assertions of those in power at the University that African Americans did not want on-campus housing. They also reveal the leadership of this work by African American students.

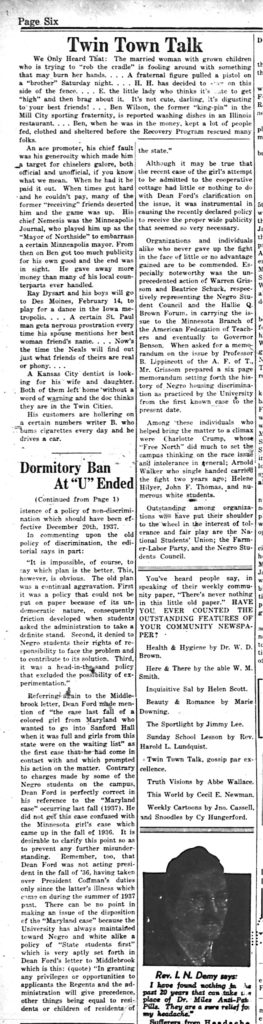

Warren Grissom attended a meeting of the Negro Student Council held at the Sterling Club in St.Paul a few days prior to his presentation to Local 44 of the AFT. The Minneapolis Spokesman noted that he “presented the case” regarding housing there and “was assured of full support of the Council in an effort to once and for all settle the issue of the Dormitory at the University.” The article also noted that “the Administration refuses to allow the matter a proper presentation before the Board of Regents, while on the other hand issu[es] statements that there is no discrimination at the University and that Negro students prefer not to live in the dormitories.”“Speaker Blames ‘U’ Administration. Teachers hear of Race Students Housing Bar” Minneapolis Spokesman, January 21, 1938, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83025247/1938-01-21/ed-1/seq-1/. The Sterling Club, founded in 1919, describes itself as the “USA’s oldest Afro-American Men’s Club” near the intersection of Dale and Rondo. This link takes you to an article about the history of the Sterling Club.

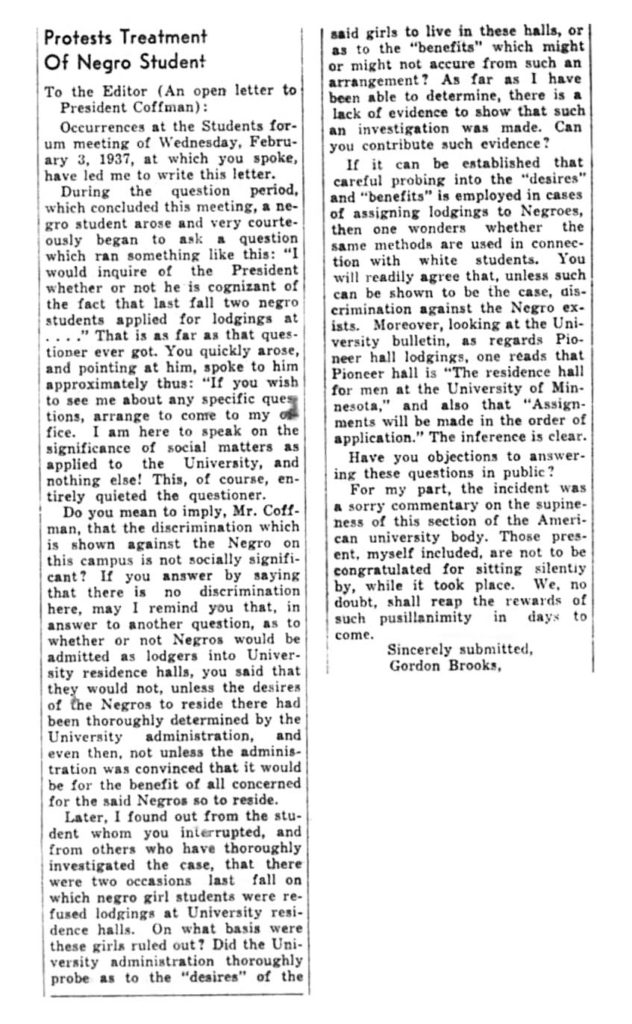

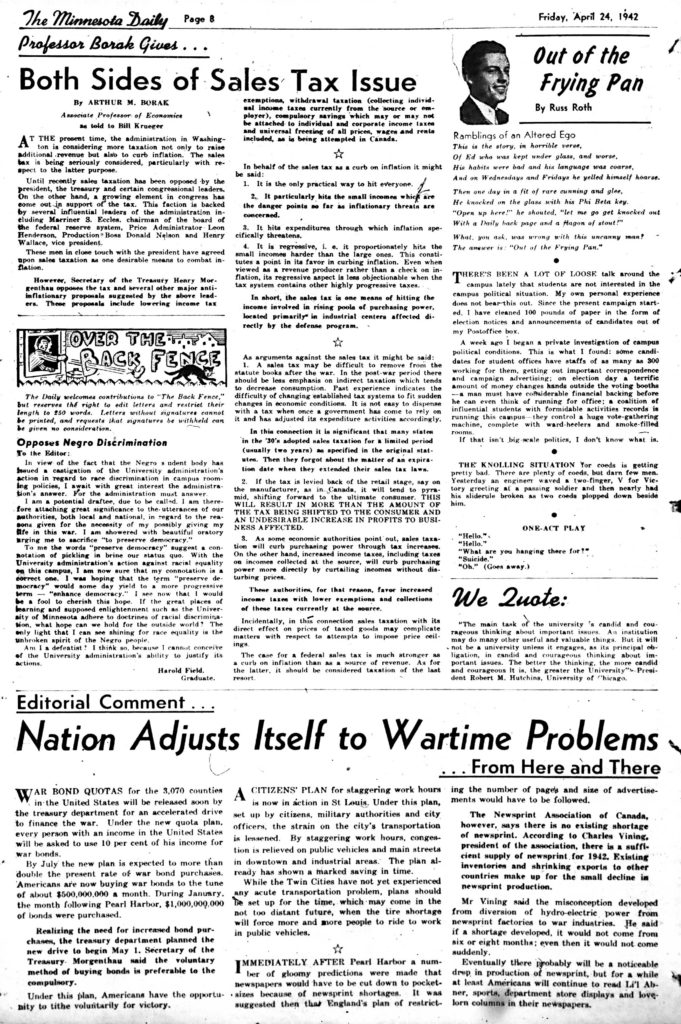

Another measure of the success of student opposition to segregated housing is apparent in what may be the first letter to appear in the Minnesota Daily challenging President Coffman and his policy. Student Gordon Brooks wrote an “open letter” to President Coffman that was published on February 5, 1937 as a Letter to the Editor (in a section called “Over the Back Fence”). This letter reveals that African American student rights in general, including the right to live on campus, were of growing concern to all students.

Brooks took the president to task for his treatment of a “Negro student” at a student forum the previous day. When the un-named student (Arnold Walker, according to the Minneapolis Spokesman) inquired of the president if he was unaware that two students were denied lodging the previous fall, Brooks noted that Coffman “pointed at the student and silenced him.” “I am here,” the president intoned, according to Brooks, “to speak on the significance of social matters as applied to the University and nothing else.” Brooks wrote, “Do you mean to imply, Mr. Coffman, that the discrimination which is shown against the Negro on this campus is not socially significant?” Brooks used the remainder of his “open letter” to castigate the president for his insistence that thorough investigations were required to learn not only if African American students wanted on-campus housing, but if it would be beneficial.

Guy Stanton Ford Ended Segregated Campus Housing from 1937-1941

Guy Stanton Ford assumed leadership of the University due to President Coffman’s illness in 1937 and subsequent death on September 22, 1938. In the fall semester, another effort was made to integrate the cooperative cottages when Audrey Beatrize, an African American undergraduate who had been barred from moving into her assigned room the previous fall, was invited by another student activist to move into an open room in the cottage where she lived. Housing Director McBeath demanded that the residents vote on whether Beatrize could move in, which had no precedent. The young women voted 60–44 against admitting her. The majority of those who voted would not have even shared living space with Ms. Beatrize.

The vote to exclude an African American student from student housing gave Acting President Ford the opportunity to stop segregation. In a letter to Comptroller William Middlebrook, he directed the immediate opening of campus housing to any student who was a resident of the State of Minnesota, regardless of race. Ms. Beatrize was to be admitted to the cooperative cottage.

Acting President Ford sent a copy of this letter to the Minnesota Daily upon the request of the editor, Jay Richter. In it he laid out his rationale for the new policy and his outrage at segregation at the University of Minnesota. Ford chose to publish the article in the student newspaper to make sure that his commitment to integration would not be undermined by those who worked with President Coffman to maintain segregation such as those in the Housing Office and others in his administration.

Ford also noted that he did not expect the Board of Regents to object to integration, and there is no record of the Regents voting on this matter again. As president, Ford was able to act independently. He wrote:

“I could not conceive of the responsible officer of this state University supported by all classes taking discriminatory action based on creed, or color, or political faith. Our classrooms are freely open to any qualified student who conforms to the purposes and procedures of an institution of higher learning. The same policy applies to our other facilities.”

The Minneapolis Spokesman reported the long-awaited end of segregated housing on campus:

“The successful culmination of the long fight against the University’s discrimination policy on housing Negro students in its various housing units was seen as a result of the statement made by the Minnesota Daily on Tuesday of this week by Dean Guy Stanton Ford, acting president in the absence of President Coffman. In a drastic reversal of what had formerly been an ‘unwritten policy,’ Dean Ford gave the Minnesota Daily a copy of a letter dated December 20th, 1937 and addressed to William T. Middlebrook, comptroller…

Organizations and individuals alike who never gave up the fight in the face of little or no advantage gained are to be commended. Especially noteworthy was the unprecedented action of Warren Grissom and Beatrice Schuck, respectively representing the Negro Student Council and the Hallie Q. Brown Forum, in carrying the issue to the Minnesota Branch of the American Federation of Teachers and eventually to Governor Benson…

Among these individuals who helped bring the matter to a climax were Charlotte Crump, whose “Free North” did much to set the campus thinking on the race issue and intolerance in general; Arnold Walker who single handed carried the fight two years ago; Helene Hilyer, John F. Thomas, and numerous white students.

Outstanding among organizations who have put their shoulder to the wheel in the interest of tolerance and fair play are the National Students’ Union [This might have been either the American Student Union or the National Student League]; the Farmer-Labor Party, and the Negro Student Council.”

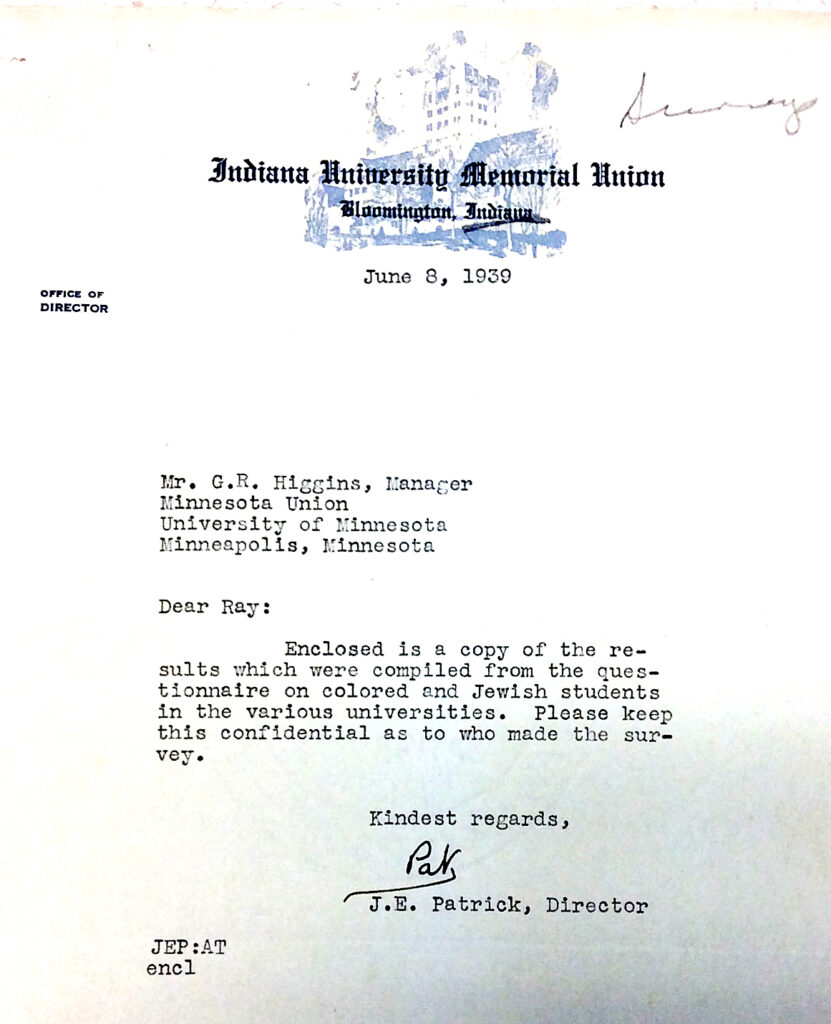

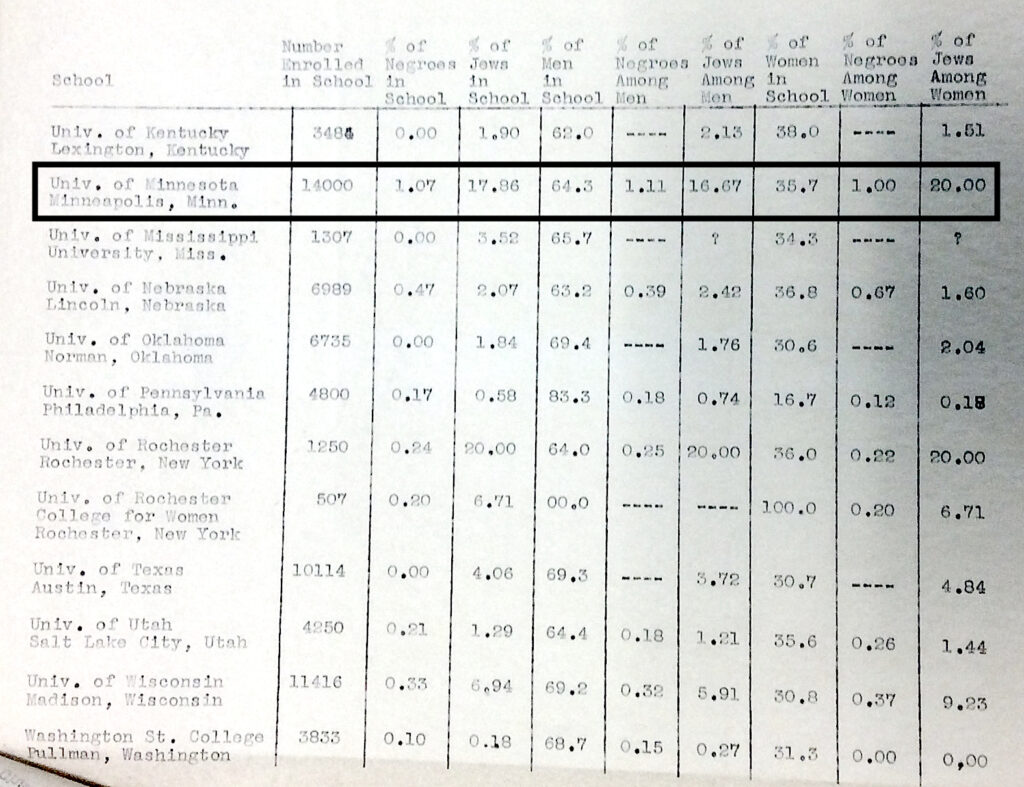

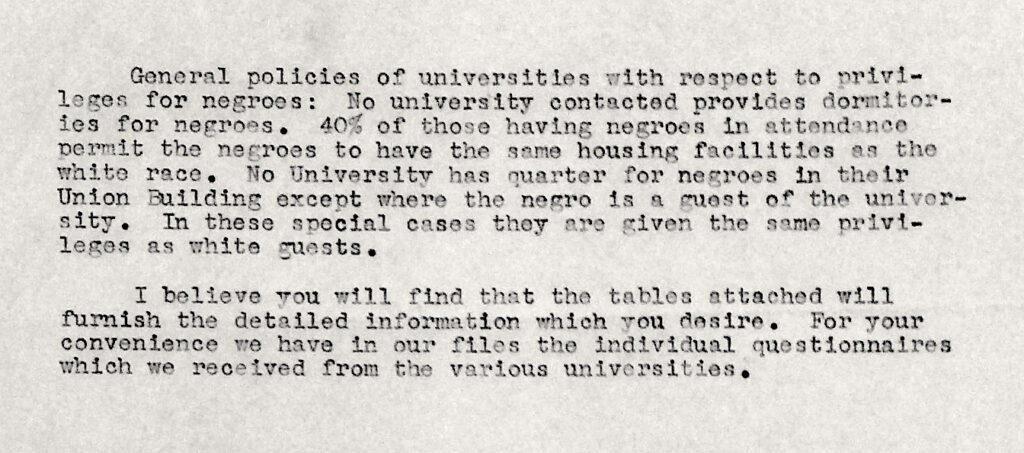

As triumphant as President Ford’s commitment to integrated housing was, there were clearly undercurrents of opposition. A file buried at the back of a file cabinet at the University of Minnesota’s Student Union reveals a correspondence between Indiana University’s Director of the Student Union and the University of Minnesota’s Student Union manager noted above. It appears that Minnesota’s Mr. Higgins was inquiring about segregated students housing and the accommodation of African American students. He learned that not a single northern or eastern university had segregated housing. Neither that norm, nor President Ford’s position, stopped University of Minnesota administrators from continuing to attempt to keep Pioneer Hall a white’s-only dormitory.

President Walter Coffey Created a Jim Crow House for African American Male Students During WWII. The Largest Mobilization Yet Against Campus Racism Followed

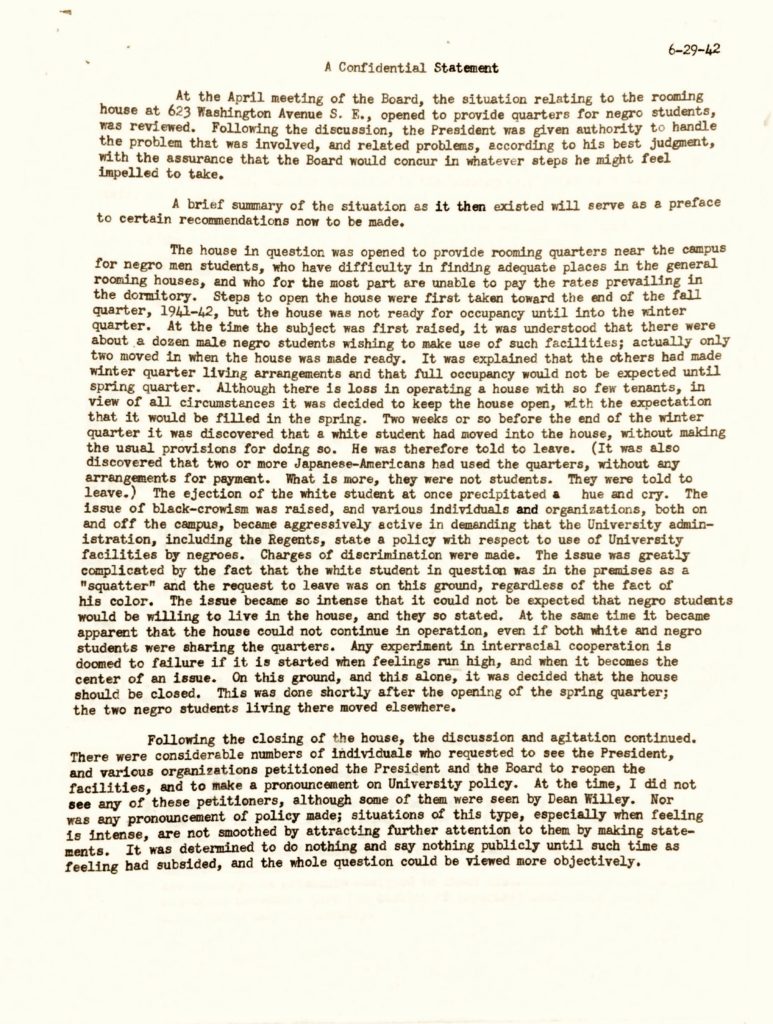

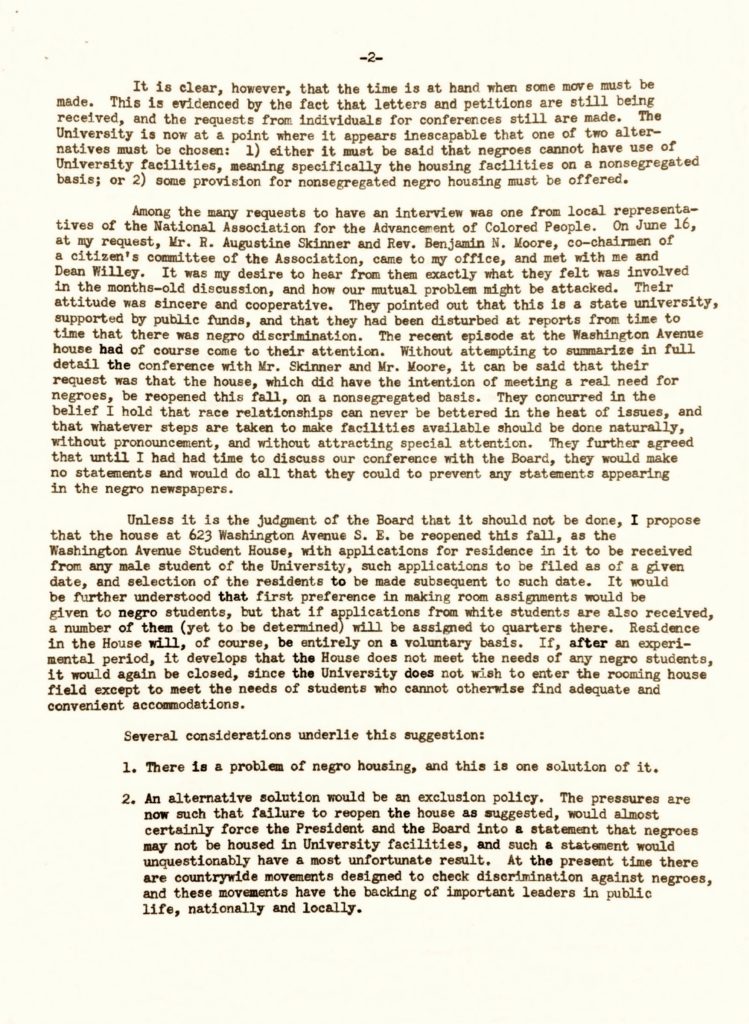

Walter Coffey became President of the University of Minnesota in 1941 on the eve of WWII, following President Ford’s mandatory retirement because of his age. He quickly undermined President Ford’s policy of integrated student housing. His staff, including Comptroller William Middlebrook and adviser Malcolm Willey, created a segregated “International House” in 1941 on 623 Washington Avenue SE, in a building owned by the University.

International in name only, it was NOT for international students, but for African American men. President Coffman had formulated this idea in the early 1930s. Several committees studied its feasibility and student interest. However, it was never built because the cost was viewed as prohibitive. While international houses were part of the landscape of higher education in this period to foster good relationships between foreign and American students, Lotus Coffman’s agenda was different. Beginning in 1931, he viewed the International House as a residence for African American male students to keep them out of other dormitories that would serve whites only.

After President Ford outlawed segregated dormitories, discussion of an international house disappeared. President Coffey, aided by the same administrators who had worked closely with Coffman on segregating housing, including Middlebrook and Willey, J. C. Poucher and V.H. Mohns, all aided the new scheme to create a residence exclusively for African American men students. Their commitment to University-segregated housing was, from their perspective, necessitated by the Phyllis Wheatley Settlement House ending housing for African American students in 1942.Report of the Task Force on Building Names and Institutional History, 22-24.

Garland Kyle, an African American graduate student in mathematics, approached the housing office about finding a suitable residence that was less expensive than a dormitory. V.H. Mohns, who headed Pioneer Hall and managed some of the business of University housing, began a discussion with him about a residence for international students, as well as African Americans. Kyle expressed interest in what he understood would be an integrated house of white, African American and foreign students. Kyle was never informed that the only residents allowed in the house would be African American. The University updated the property for $6,000.00 ($100,000.00 in current dollars) and anticipated students moving in during the spring term.

Kyle’s original roommate, who was African American, decided not to move in, and Kyle was subsequently joined by a white student as a roommate. Other white students, as well as Japanese American students awaiting admission to the University during the period of Japanese American citizens’ internment, wanted to join them. Some applied and were rejected for being white. Some students simply moved in. When Mohns was informed a white student was living in the house, he shut it down and locked out all of the residents. The University agreed to sacrifice their $6,000 investment to avoid integrated housing.

Mohns, among others, claimed certain “facts” about what led to the closing of what was typically referred to as the Washington property. He insisted that Kyle had agreed to a segregated residence, which Kyle denied. Kyle’s view was supported by a crucial office memorandum written by Coffey’s assistant, Malcolm Willey on March 24, 1942. It recounted a meeting between Willey and Judge Edward Foote Waite (1860-1958). Retired by then, Judge Waite lived a life in public service, including twenty years of presiding over juvenile court. For twenty years following his retirement, he continued to work to overcome “racial prejudice” and racial segregation in the public schools. He joined the board of the Urban League just as the conflict over the Washington Avenue house came to light.Mary Treacy, “Waite, Edward Foote (1860–1958),” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society, http://www.mnopedia.org/person/waite-edward-foote-1860-1958.

Judge Waite contacted Willey about the house on Washington Avenue. He had met with Garland Kyle and another African American student and learned with alarm about the University’s insistence that only “negro” (Willey never capitalized the word) students would be residents. He explicitly asked Willey if a Japanese or Chinese student would be able to live in the house. With striking dishonesty, Willey explained that was not possible since there were “adequate rooms for them on the campus.” He provided no evidence of that, and most boarding houses in the area excluded Asian-American students from housing.

When Judge Waite commended the University for having an African American student living in Pioneer Hall, Willey made no effort to correct that point. Moses Blackwell, the student to whom he referred, was being pressured to move into the segregated house on Washington Avenue. The student demanded that housing services write to his father to inform him that Blackwell had no other place to live, and that was why he was being asked to move. It is unclear if Blackwell moved into the house. He was never listed as a resident.Vern Mohns Memo for President Coffey, Administration, Alphabetical, Negro, 1939-1942, box 20, folder 21, 69, University of Minnesota Libraries, UMedia Archive; Vernes Mohns to Coffey, memo, 24 March 1942, Administration, Alphabetical, Negro 1939-1942, box 20, folder 21, 67, University of Minnesota Libraries, UMedia Archive. It is worthy of note that Mohns spied for Dean Edward Nicholson on at least one left-wing student group meeting and his report is found in Chase papers. This is detailed in the essay on Political Surveillance of the University.

Willey’s memo reveals that the University had no intention of creating an “international house.” Rather, the sole purpose of the house was to segregate African American male students, and to keep all other dormitories white. “The Statement of Facts” also affirmed that reality. It simply misstated the assent of African American residents.

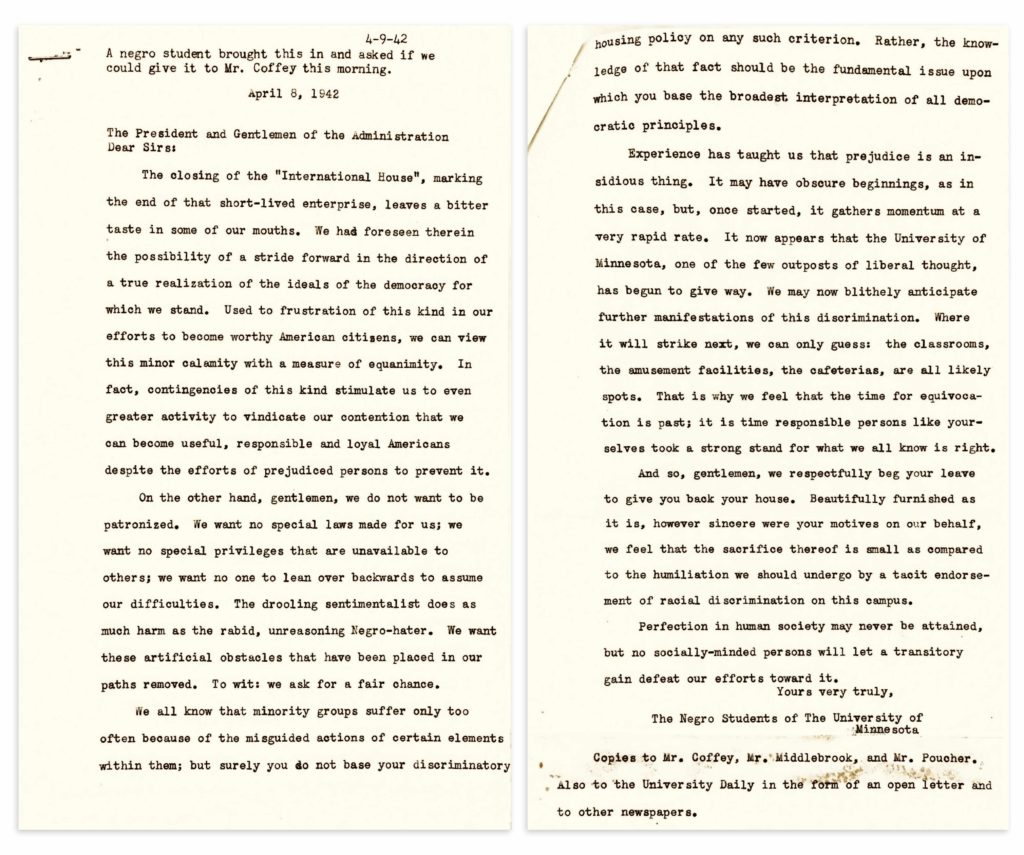

Unprecedented Mobilization—Calling Out Segregation in Wartime

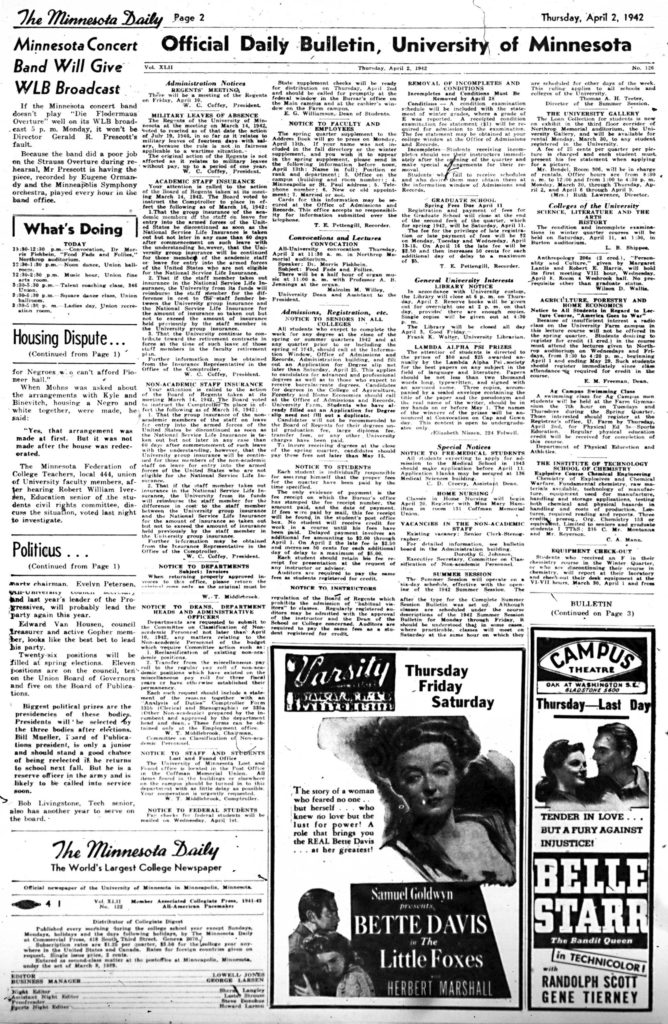

A student uprising followed. If the fight to integrate housing in 1935 involved a few dozen students, the fight in 1942 involved over a thousand students. With the United States at war to fight for democracy in Europe, this blatant racism was noted by the activists on and off campus. Within a short time, African American students on campus acted together to protest the University’s insistence that the International House remain segregated.

The Minnesota Daily reported in detail over many weeks on the events related to the University closing the International House because it was integrated, and Garland Kyle, the graduate student and resident in the house, became one of the most important leaders of the protest.

The Civil Rights Committee, an integrated group of student activists chaired by Leonard Lecht, campaigned to expose and defeat the segregated housing on campus as well. This group held its regular meetings at the Washington Avenue House, as Mohns noted with disapproval. He also noted that white members of the group applied to room there as well.

Along with many other campus organizations, the Civil Rights Committee pressured President Coffey to make a public statement on whether the University of Minnesota supported segregated housing. Its members would not back down from demanding the statement, and no member of the Coffey administration responded to the demand.

These activists built alliances with multiple student groups on campus, collected 1,200 signatures on a petition opposing segregation, organized rallies, and demanded that all student political parties with candidates running for election to the All-University Council publicly take a stand for or against segregated housing. The majority of the All-University Council voted to clarify the housing policy but rejected supporting integration.

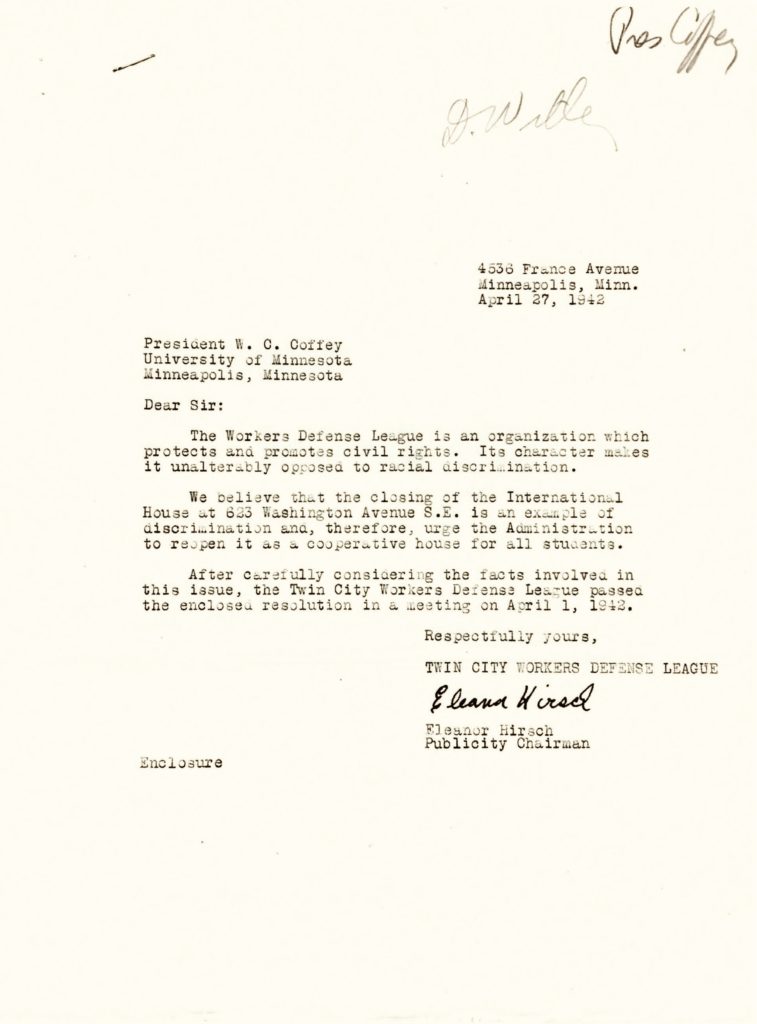

A “Committee of Six” emerged to support the student activists that included representatives of the NAACP chapters in Minneapolis and St. Paul, the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, Minnesota Branch, and the American Federation of Teachers Local 44.

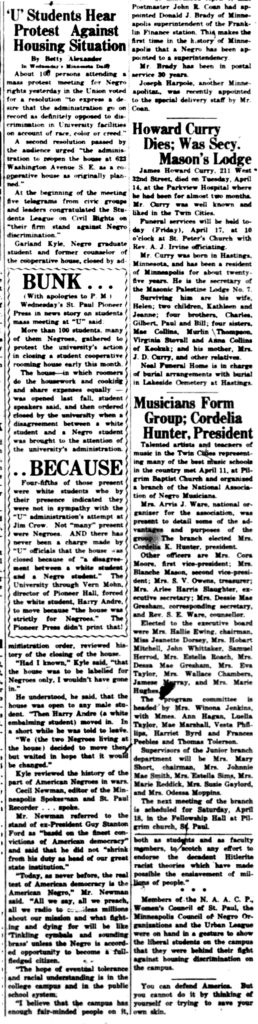

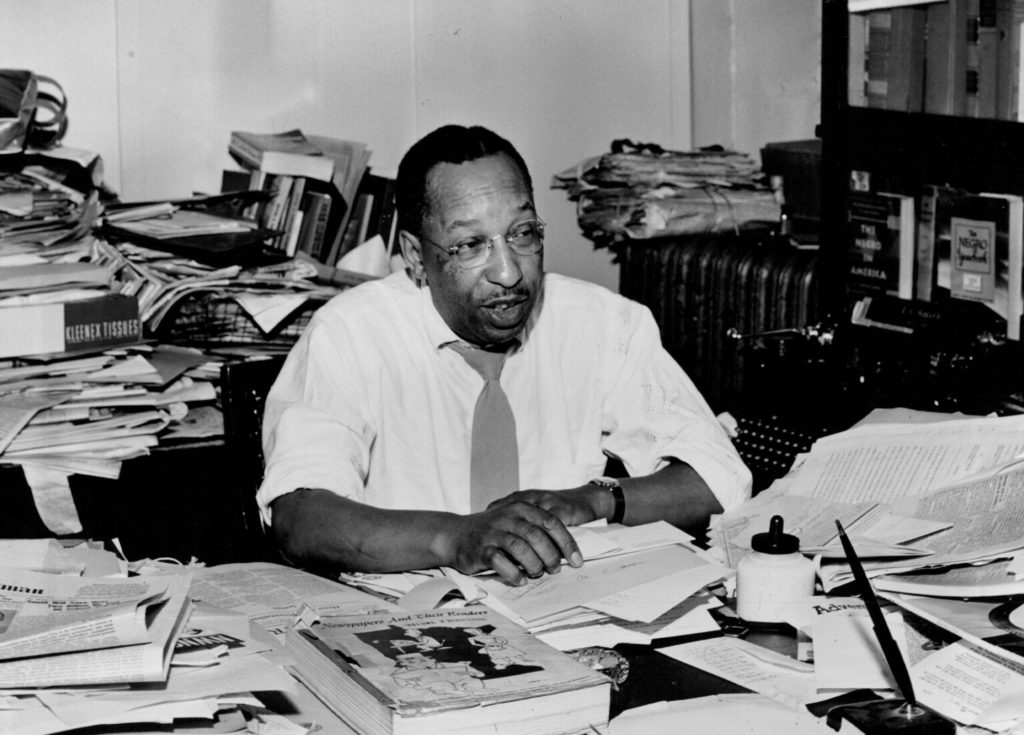

The Civil Rights Committee organized an April protest at Coffman Union where over 100 people rallied and heard from Garland Kyle and Cecil Newman, editor of the African American newspapers Spokesman and St. Paul Recorder. The Minneapolis Spokesman offered the fullest account of the event.

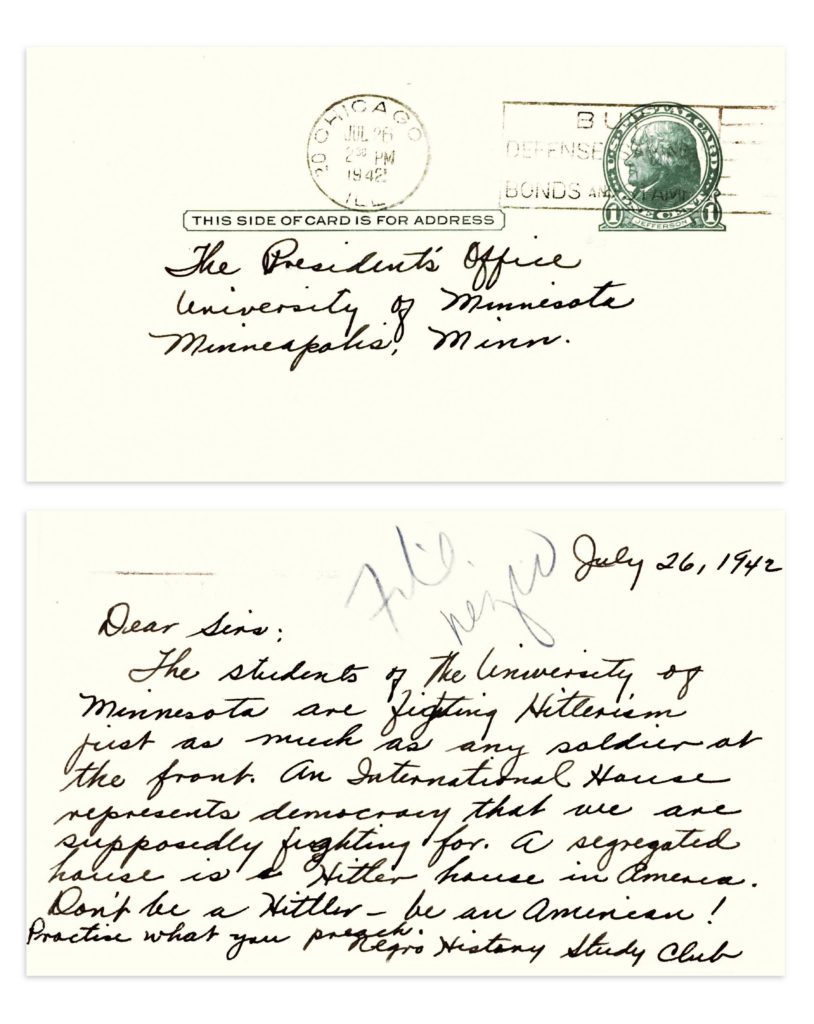

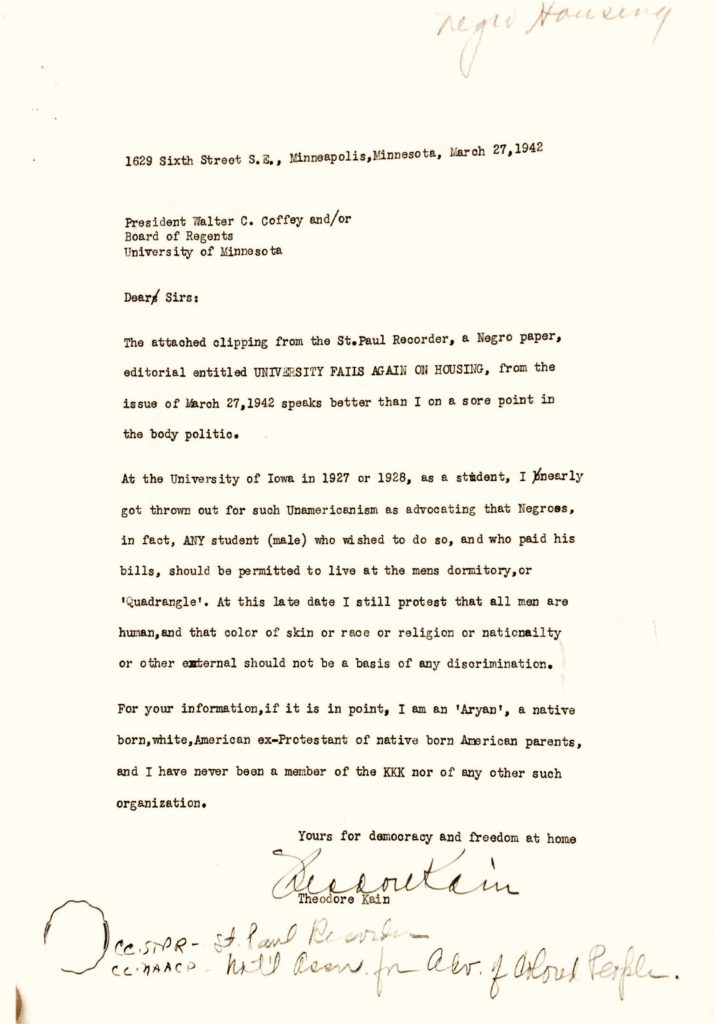

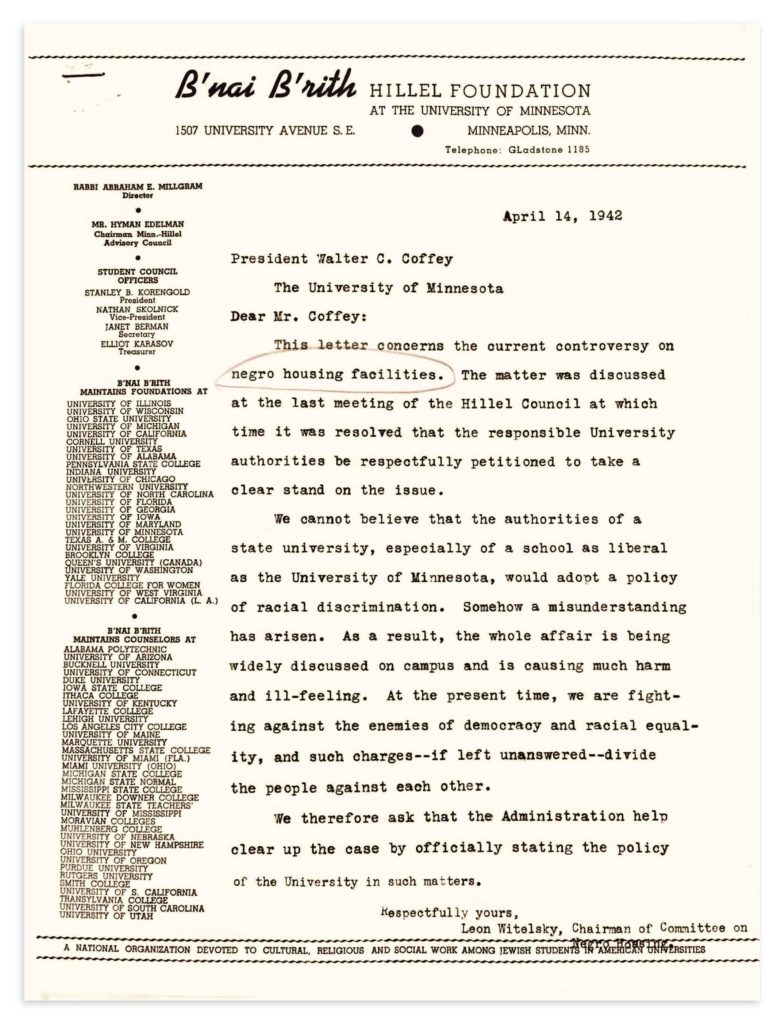

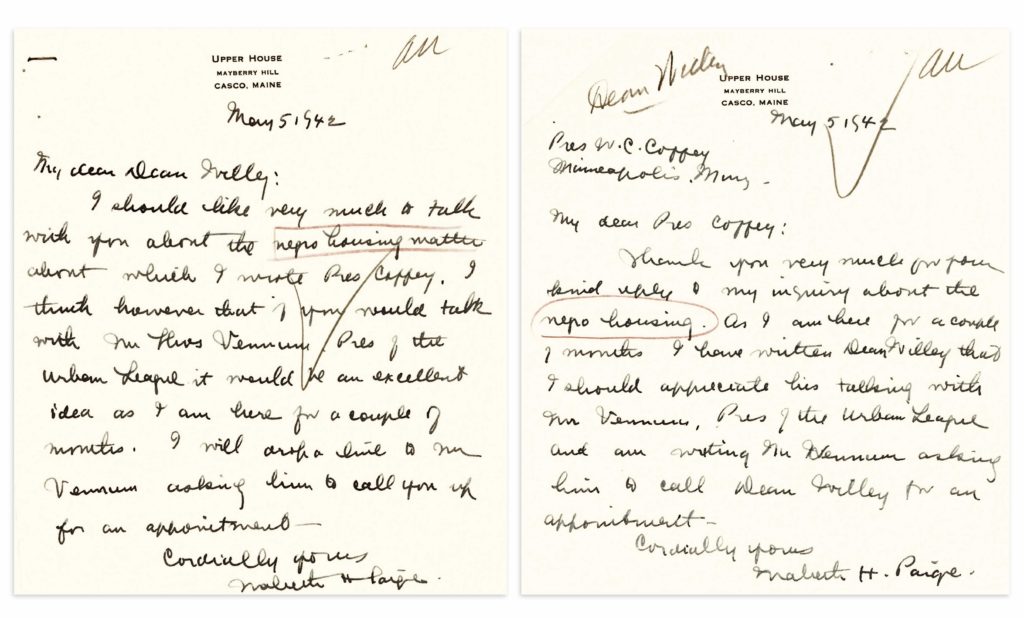

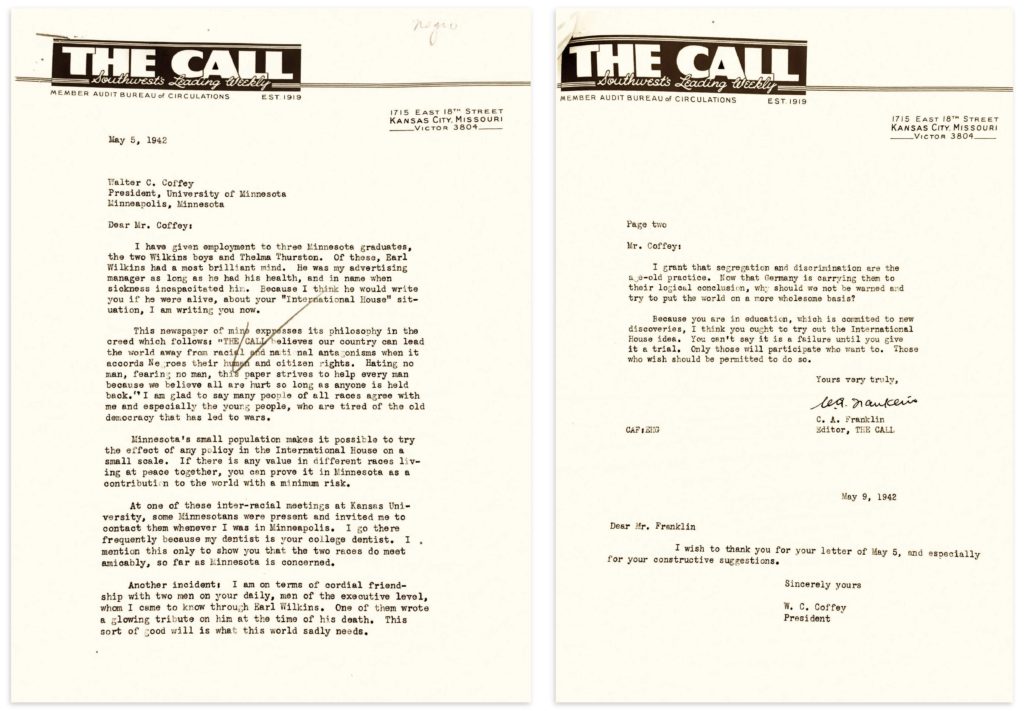

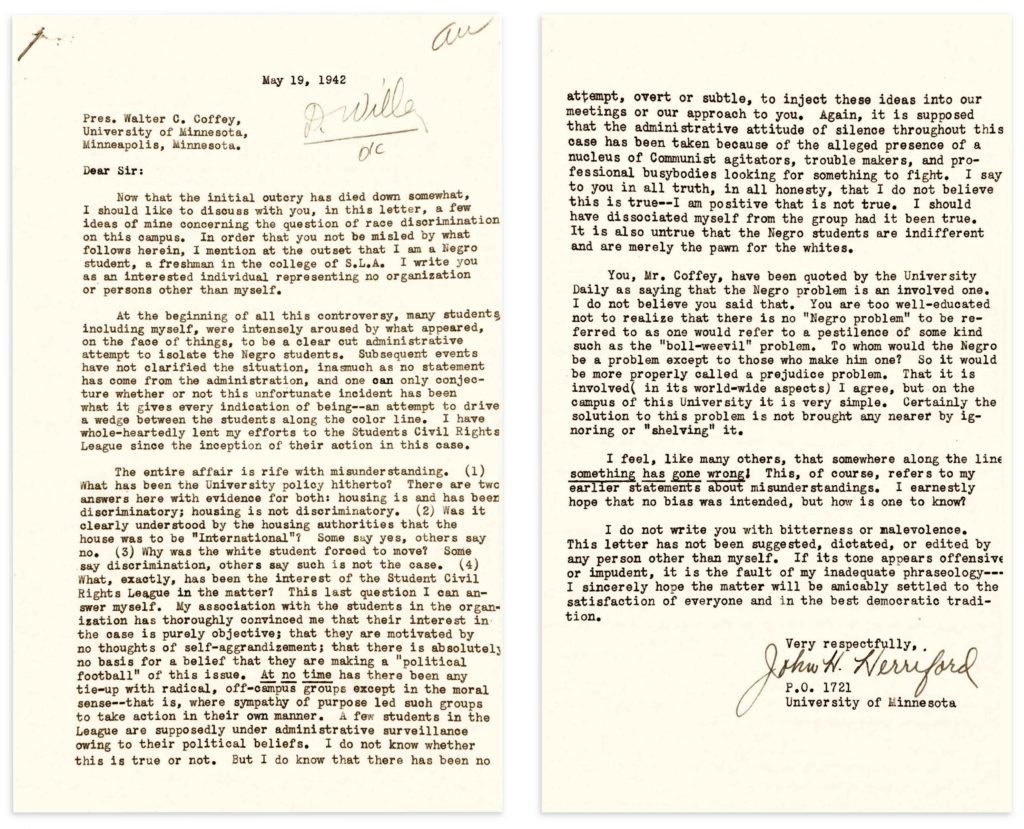

Letters, post cards, and petitions from the Twin Cities and nationally poured into the University to condemn segregated housing. The letter writing campaign revealed that activists on and off campus were effectively mobilizing a variety of allies. These letters were addressed to President Coffey and took a variety of approaches to the problem of segregated housing.

They came from the Chicago Negro History Study Club, the University of Minnesota Hillel, the Central States Cooperative Movement, the Youth Committee for Democracy (based in New York City), the Minnesota State Federation of Teachers, the Jewish Anti-Defamation Council, Minnesota Representative Mabeth Paige (Republican) who served in the Minnesota House from 1923-1945, and the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. Some letters and petitions compared on-campus segregation to Nazi policies, and others wrote about the importance of “tolerance” and ending prejudice for the future. They all described segregation on-campus as an intolerable and unacceptable practice.

The segregated International House prompted letters to the Minnesota Daily and other Minneapolis newspapers as well as national news coverage. Harold Field, an alumnus of the University of Minnesota, wrote with outrage to the Daily about the International House as he anticipated being drafted to fight in WWII in the coming days.

President W. C. Coffey Refused to Meet with or Reply to Students or Faculty About the Jim Crow House Until Organized Resistance Finally Succeeded

President Coffey remained silent throughout the weeks and months of protests and also forbade his staff to speak to anyone about the issue. He was invited by the on-campus Civil Rights Committee to meet with its members at the Phyllis Wheatley House, the Settlement House serving African Americans in Minneapolis, on April 24, 1942. The integrated group of student activists had strong ties in the African American community. Seven student groups, including the All-University Council, the Fabian Club, the Student Civil Rights League, the Student Social Workers Association, the Hillel Foundation, the Progressive Party, and the Northrop Club issued another invitation to President Coffey to speak at a meeting on May 6, 1942 at Coffman Memorial Union. He refused to attend either meeting.

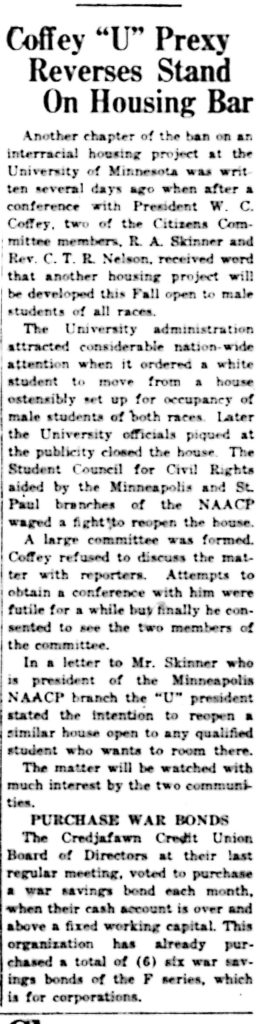

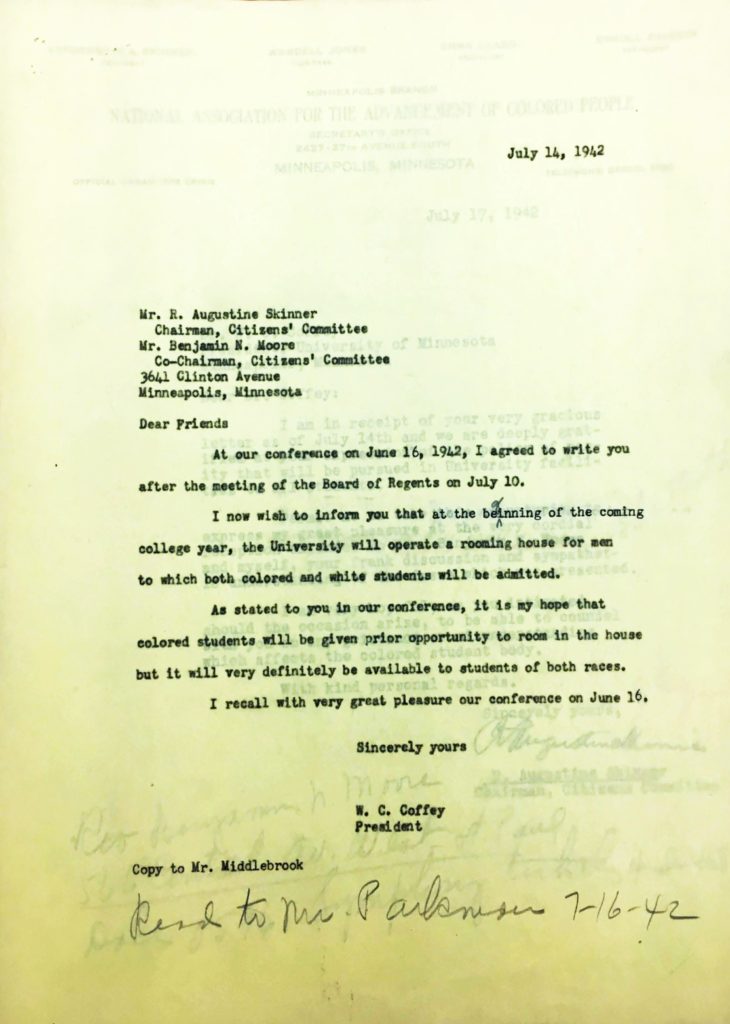

It was not until the summer of 1942, and only after continued pressure from the NAACP and its allies, that President Coffey relented. He met with two representatives of the Committee of Six and assured them that the University of Minnesota would end segregated housing. The two Minnesota Daily articles below chart the President’s refusal to meet with students about University segregated student housing.

The small size of the African American community in the Twin Cities had consistently made political effectiveness challenging. In the 1930s, however, a new generation of leadership emerged from the labor movement that gave rise to a different and more effective type of political activism. African American activists such as Nellie Stone Johnson, Cecil Newman, and Anthony Cassius built on their union work with the Pullman Porters and hospitality industry to create a strong political movement for African American rights grounded in their own independent organizations. Alliances with the Farmer-Labor and Democratic-Farmer-Labor Parties were important to realizing a broader national commitment to civil rights. During the struggle for racial integration in housing at the University of Minnesota in 1942, this growing strength was already apparent.Jennifer Delton, “Labor, Politics, and African Identity in Minneapolis, 1930-1950,” Minnesota History 57, no. 8 (Winter 2001-2002): 419-434.

The University Betrayed Its Commitment to the Principle of Integrated Student Housing

President Coffey promised R. A. Skinner and Rev. C. T. R. Nelson, leaders of the Committee of Six, (also called the Citizens’ Committee) that the University would integrate the International House.

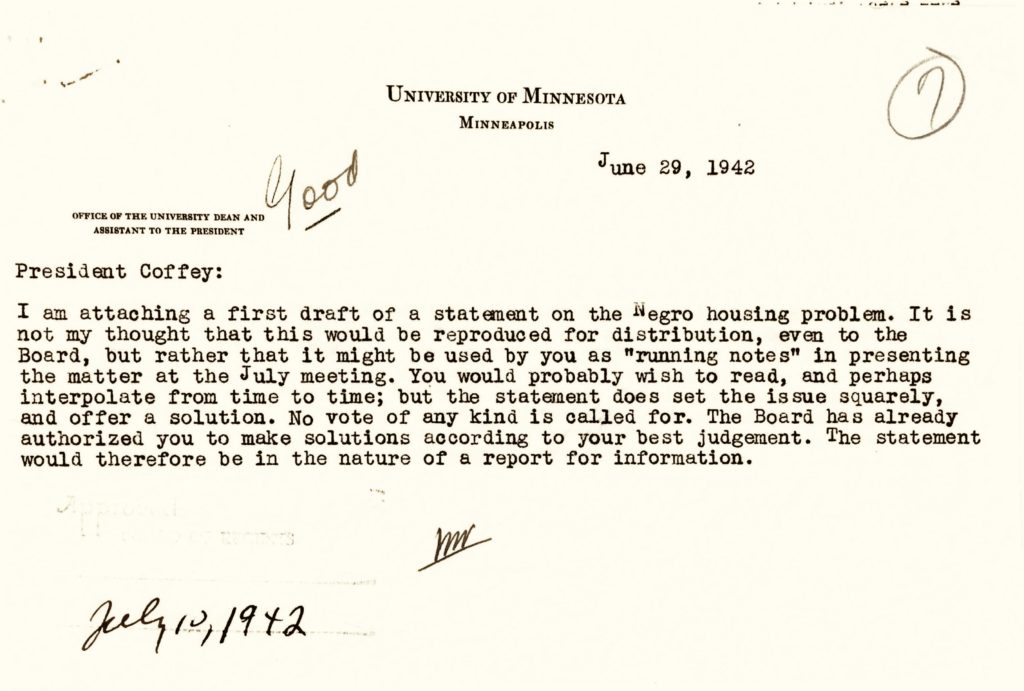

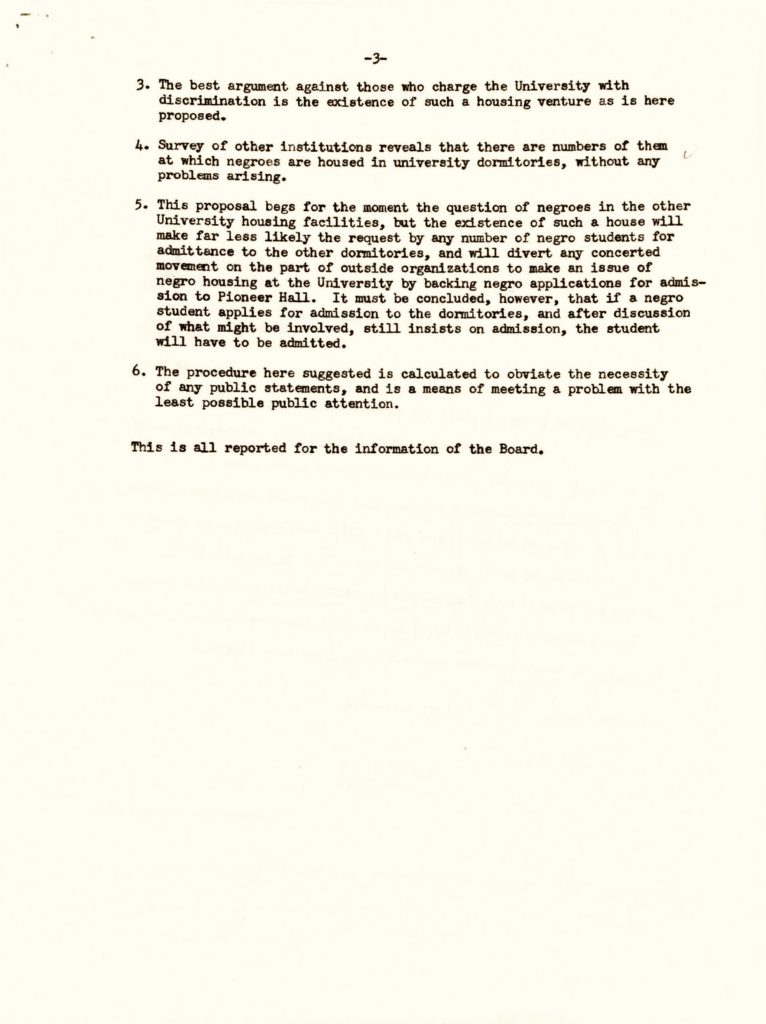

However, at the same time Skinner and Nelson received these assurances the president’s staff had been hard at work a few weeks earlier proposing ways to undermine the integration of all other student housing. The staff and President Coffey were particularly committed to avoiding making any public statement that either supported integrated housing or denied the University’s commitment to it. Coffey’s assistant Dean Malcolm Willey wrote an office memorandum about the future of student housing. He met with five other administrators to put the plan into action. Their goal was to maintain, as much as it was possible, Pioneer Hall as an exclusively white male residence hall.

Willey’s plan required newly appointed Dean of Student Affairs Edmund Williamson to meet individually with every African American student who applied to live in Pioneer Hall in the fall of 1942 to counsel him to move into the International House, which was now renamed the Washington Avenue Student House. If the student insisted on living in Pioneer Hall, then Dean Williams would advise him of the rules he would be required to live by. This condescending admonition suggested that African American students were less willing to follow rules than white students.

However, the memo revealed that Dean Willey also advised the president that African American students could no longer be “kept out” of a dormitory. This reluctant conclusion suggested both how deeply the administration clung to the importance of segregation and the lack of legal or moral support for it by 1942. Administrators actively feared publicly endorsing integrated housing, and memos reveal their ongoing anxiety about African American and white students socializing together in dormitories more than a decade after President Coffman’s racist declaration that segregation was “healthy” for white and “Negro” students.

Into the Post War Years

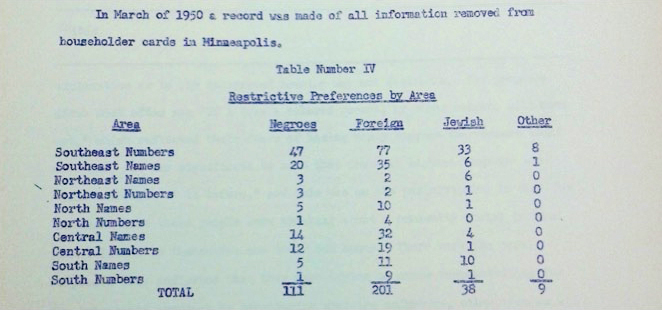

By 1942, the University of Minnesota was one of the last Big Ten schools to still have segregated housing. While campus housing was at last integrated (in principle), boarding houses approved by the University continued to discriminate against Jews and African Americans. During the war years, householders could also refuse foreign and Japanese American students. A University of Minnesota oral history project included an interview with Professor David Cooperman (1927–1998) of the Department of Sociology, who was also a founding faculty member of the University’s Center for Jewish Studies. Cooperman was a graduate student and teaching assistant at the University in the 1950s and a member of the on-campus Student NAACP.

Cooperman recalled that in 1948 or 1949 student activists demanded that the University reject boarding house segregation. He recounted, “Black students discovered that Dean Williamson’s housing office was noting on cards any communication from a landlord: ‘No Negroes accepted in this house.’ We went to Dean Williamson and said, ‘This is discrimination.'” Cooperman recalled Dean Williamson’s response to the students in his office when he boomed, “You’re absolutely stupid! This isn’t discrimination, and so long as I’m Dean of Students, we’re going to make these notations.” Professor Cooperman explained that the Student NAACP appealed directly to President James Lewis Morrill (1891–1979), President of the University of Minnesota from 1945 to 1960, who stopped the policy. Cooperman added that Dean Williamson became an advocate in favor of the rights of students from marginalized groups in just the next few years.David Cooperman, interview by Clarke A. Chambers, July 30, 1984, Digital Conservancy of the University of Minnesota Libraries, 28-29, https://conservancy.umn.edu/handle/11299/47858.

Yet, one other presidential directive to integrate student housing was foiled because the policy did not change until 1954, when exclusion of African Americans, Jews, and Asian Americans was finally stopped by the University Senate.

Conclusion

The history of the University of Minnesota’s policies on the exclusion of students from University housing by race and religion is a story of the persistence of racism and antisemitism, enforced by administrators who often ignored directives of presidents of the institution. The hundreds of documents and newspaper reports included in this website’s digital archive still provide an incomplete story, not only of the persistence of a racial hierarchy, but of the indignities and pain suffered by generations of students. The fight at the University of Minnesota to open the housing doors to all students came later than to most private and public universities in the north and remains a legacy of both racism and the courageous activism of students and their allies to fight it.