Antisemitism at the University of Minnesota

Minnesota Jews and Antisemitism from 1920-1948

Jews arrived in the Twin Cities and other regions of Minnesota as a result of immigration from German lands and Eastern Europe from the mid-19th century to the closing of Eastern European immigration in the 1920s. By 1910, the Twin Cities Jewish population had doubled to 13,000 people, reaching a peak of 44,000 people in 1939.

The “tribal twenties” in America were marked by racism, antisemitism, and anti-Catholicism. The Depression era of the 1930s further magnified discrimination. During that difficult decade, virulent antisemitism was advanced by the Ku Klux Klan, beginning in the 1920s, and a variety of other popular fascist organizations with a strong following in Minnesota.An excellent analysis of the KKK is found in Linda Gordon, The Second Coming of the KKK: The Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s and the American Political Tradition (New York: Norton Publisher, 2017).

In the 1930s, with the nation in the midst of the Depression, extremist movements flourished, particularly in the Midwest and Minnesota. The United States was awash in organizations whose platforms rested on anti-communism and antisemitism and reflected the growing successes of Nazism and fascism in Europe. Scholars understand the 1930s as a period of unprecedented antisemitism in the nation’s history. On the eve of the United States entering WWII and throughout the war’s duration, the attacks only increased. Demagogic leaders blamed Jews for economic failures, for undue influence over political leaders (especially Franklin Delano Roosevelt), for capitalism, for the Bolshevik triumph in Russia, and for the failures of the New Deal. Many claimed that the nation was under the control of a handful of Jewish men, a list that often included Louis Brandeis (1856-1941), Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, Felix Frankfurter (1882-1965), Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, and Henry Morgenthau (1891-1967), Secretary of the Treasury to Franklin Delano Roosevelt, among others.Leonard Dinnerstein, Anti-Semitism in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 109; Michael Gerald Rapp, An Historic Overview of Antisemitism in Minnesota, 1920-1960 with Particular Emphasis on Minneapolis and St. Paul (PhD dissertation, University of Minnesota, 1977), 59-83.

Tens of thousands of Americans found theories of Jewish conspiracies, power, and manipulation entirely convincing. They joined organizations, listened to radio broadcasts attacking Jews, and distributed leaflets “proving” these conspiracies. Many churches were led by men who preached these ideas from their pulpits on Sundays.

In Minnesota, Republicans, leaders of big business, churches, and right-wing organizations created disturbing alliances. Among the most prominent fascist, pro-Nazi groups were the German American Bund, the Silver Shirts (Silver Legion), and the Christian Nation. Three smaller organizations were headquartered in Minnesota in the mid-1930s, some only briefly. They were the Christian Vigilantes of Minneapolis, the Pro-Christian American Society, and the White Shirts in Virginia, Minnesota. Each combined an anti-Farmer-Labor, anti-union perspective with Christianity and antisemitism.For a discussion of these groups in Minneapolis in the 1930s see Samuel G. Freedman, Into the Bright Sunshine: Young Hubert Humphrey and the Fight for Civil Rights (New York: Oxford Press, 2024), 108-133.

The Silver Shirts organization was founded by William Dudley Pelley (1890-1965). His organization grew and contracted throughout the 1930s, with a solid base of supporters in 1936 in Minneapolis. The Silver Shirts welcomed any person over 18 who was not Jewish or African American. Members were required to read, in addition to Pelley’s writing, the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a fabricated tract that originated in Russia and became one of the most important weapons of antisemitism in the 20th century. It posited the existence of a Jewish world-wide conspiracy aimed to control the world and originated ideas of secret cabals and Jewish plans to enact world domination. It continues to animate 21st-century white supremacists, Christian nationalists, and antisemites all over the world.The fullest discussion of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion may be found in Steven J. Zipperstein, Pogrom: Kishinev and the Tilt of History (New York: Liverwright Publishing, 2018). John Higham discusses how the Protocols came to the United States and the role it played in anti-radical nativism in the 1920s in John Higham, Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism 1860-1925 (New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1983). Henry Ford had the Protocols translated and published in the Dearborn Independent, his newspaper. He then published the serialized translation as a book. He claimed that Jews weakened the nation through jazz, communism banking, and unionism, among other accusations. See Neil Baldwin, Henry Ford and the Jews: The Mass Production of Hate (New York: Public Affairs Press, 2001).

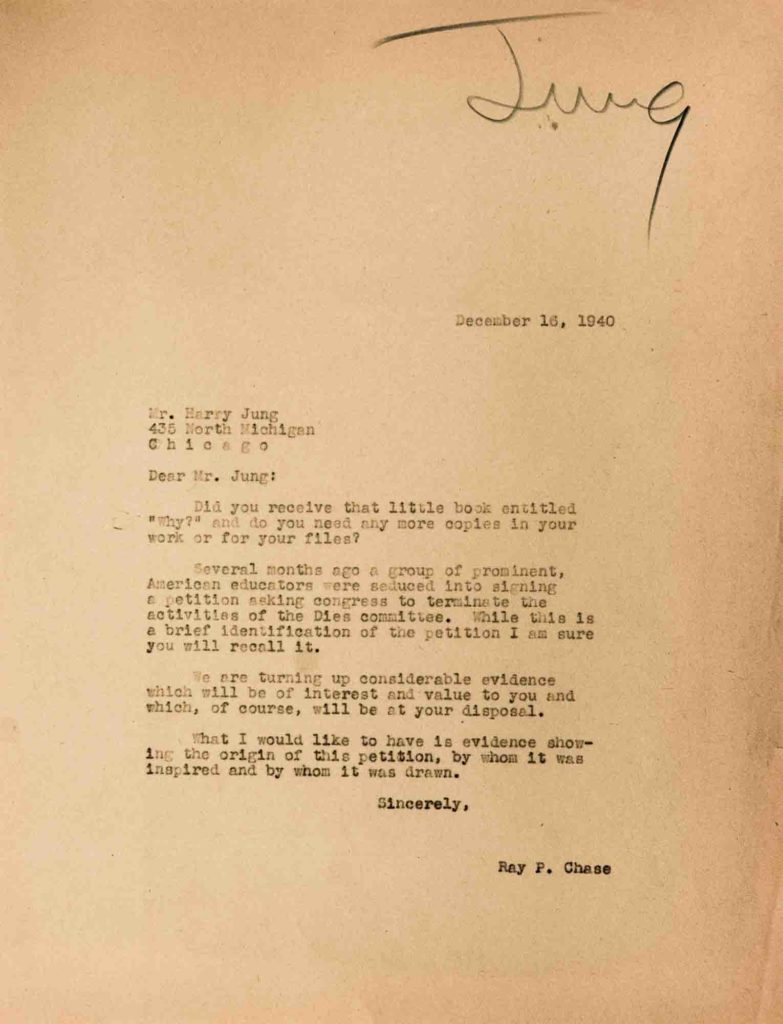

The American Vigilant Intelligence Federation was another antisemitic and pro-Nazi organization that distributed newspapers and pro-Nazi and anti-New Deal propaganda. It drew funding for its publications from both Nazi Germany and Americans who were Nazis, as well as anti-Communists. Not only did its founder, Harry A. Jung, have an active following in the Midwest, but Ray Chase, a close ally of Dean of Student Affairs Edward Nicholson, avidly pursued a relationship with him that involved trading “information” that was used to attack their shared enemies. That relationship is discussed in the essay for this website Political Surveillance of the University.This link takes you to an article about the American Vigilante Intelligence Federation from the archive of the Jewish Telegraphic Agency published in 1934.

The followers of this nativist, antisemitic, fascist organization were first exposed in the Minneapolis Journal in a five-part series by Arnold Eric Sevareid in September of 1936 which he wrote shortly after graduating from the University of Minnesota. Pelley’s battle cry was “Down with the Reds and out with the Jews.” William Millikan, A Union Against Unions: The Minneapolis Citizens Alliance and Its Fight Against Organized Labor, 1903-1947 (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2001), 336-337; Sarah Atwood, “’This List Not Complete’: Minnesota’s Jewish Resistance to the Silver Legion of America, 1936–1940,” Minnesota History 66, no. 8 (Winter 2019): 145-150; Joe Allen, “It Can’t Happen Here: Confronting the Fascist Threat in America in the 1930s,” International Socialist Review 85 (September 2012), https://isreview.org/issue/85/it-cant-happen-here; Eric Sevareid, Not So Wild a Dream (First published 1946; reprint Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1995), 69-71. Sevareid’s articles from the Minneapolis Journal include “New Silver Shirt Clan With Incredible Credo,” Sept. 11, 1936; “Silvershirts Meet Secretly Here But Come Out Openly in Pacific Coast Drive,” Sept. 12, 1936; “Silvershirts Hoard Food In Readiness for Siege Foretold by Pyramids,” Sept. 13, 1936; “Silver Shirts Here Elevate Maurice Rose To Status Of International Banker,” Sept. 14, 1936; “Silver Shirts Say Quarters Are Bought by Morgenthau in Russia at 5 Cents Each”, Sept. 15, 1936; “Silvershirts’ Dire Prophecy Falls Flat; World Goes On With A Chuckle Over Plot,” Sept. 16, 1936.

If these groups were only marginally successful in the Twin Cities, that was not the case for the followers of Father Charles Coughlin (1891-1979). He established a parish in Detroit in the 1920s and began radio broadcasts in 1926. He began to fuse politics with religious services by the late 1920s and had a large following by the stock market crash in 1929. Father Coughlin began as an anti-communist crusader in 1930, first as a supporter of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal and then as the New Deal’s ardent critic beginning in 1935. His audience reached tens of millions as his broadcasts grew increasingly antisemitic with the rise of National Socialism and fascism in Europe. He supported violence against Jews in Germany and elsewhere because of “Jewish persecution of Christians” and Communist theft of Christian resources, all blamed on Jews. Coughlin grew more isolationist and insisted that the United States’ entry into WWII after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941 was the work of Jews. Ultimately, he was denied use of the United States mail or the airwaves because he was deemed a threat to the nation. His Archbishop demanded he give up all political activity or face defrocking.United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Holocaust Encyclopedia, s.v. “Charles E. Coughlin,”accessed July 22, 2019, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/charles-e-coughlin; Alan Brinkley, Voices of Protest: Huey Long, Father Coughlin and the Great Depression (New York: Vintage Books 1983); Leonard Dinnerstein, Anti-Semitism in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 105-149.

Father Coughlin called on his followers to create small cells of like-minded people and encourage members to recruit other such groups. Ultimately, he believed he would mobilize these people to rise up together and follow him. His call to organize cells was successful in Minneapolis, where these groups were known as the Christian Front. They flourished from 1939 to early 1941. In October of 1939 they held a rally attended by nearly 3,000 Minnesotans. Like William Pelley and Henry Ford, Coughlin also embraced the Protocols of the Elders of Zion and published it in 1938 in his publication Social Justice, even after Ford had disavowed it.Steven J. Keillor, Hjalmar Petersen of Minnesota: The Politics of Provincial Independence (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1987) 153, 154, 163, 298 n146. There were many other organizations in the Twin Cities, including additional churches, committed to isolationism and antisemitism.This is discussed in Michael Gerald Rapp, An Historic Overview of Antisemitism in Minnesota, 1920-1960 with Particular Emphasis on Minneapolis and St. Paul (PhD dissertation, University of Minnesota, 1977).

In this deeply unsettling period, the majority of Jews in Minneapolis and St. Paul worked in blue collar jobs. There were, however, Jewish professionals—doctors and lawyers—and they were excluded from law firms and from practicing medicine in hospitals. Their exclusion led them to open law firms where Jews could practice, and to building Mount Sinai Hospital in 1951, a non-sectarian, private hospital. Jews faced widespread discrimination in employment.Laura Weber, “Gentiles Preferred: Minneapolis Jews and Employment,” Minnesota History 51, no. 5 (Spring 1991): 167-182.

Historically, deep bonds of association were a part of Jewish life and intensified in the face of virulent antisemitism. Synagogues, educational institutions, philanthropic and social organizations, as well as Zionist groups were all part of Jewish life in the Twin Cities and in other areas of the state throughout the interwar period and beyond it. Minnesota Jews were very active in political life in this period, often associated with Farmer-Labor and ultimately the Democratic Farmer-Labor Party, as well as the Republican Party. One of the most important organizations that developed in this period was the Anti-Defamation Council, which would become the Jewish Community Relations Council. Its leadership carefully monitored all the activities of the many hate groups of the 1930s and made public their attacks on Jews as attacks on America.Hyman Berman and Linda Mack Schloff, Jews in Minnesota (St Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2002), 12-52; Sarah Atwood, “’This List Not Complete’: Minnesota’s Jewish Resistance to the Silver Legion of America, 1936–1940, Minnesota History 66, no. 8 (Winter 2019): 143; Michael Gerald Rapp, An Historic Overview of Antisemitism in Minnesota, 1920-1960 with Particular Emphasis on Minneapolis and St. Paul (PhD dissertation, University of Minnesota, 1977).

Jews, particularly in Minneapolis, were shut out of civic life and social organizations. Discrimination in employment and housing was legal and accepted. Jews in the Twin Cities were restricted from buying homes and property in many parts of the cities, and few northern Minnesota resorts welcomed them.

As discrimination was outlawed beginning in the 1940s, opportunities for Jews increased and antisemitism decreased–although never entirely disappeared–until its resurgence as a result of the rise of white and Christian nationalism and neo-Nazism in the first decades of the 21st century.

Jewish Students at the University of Minnesota

Jewish students had been attending the University for many decades by the 1930s. They came from the Twin Cities, from the smaller towns and cities of Minnesota, and also from out of state. Because of pervasive antisemitism, Jews were viewed as different from other white students for many reasons. They were not Christian, many of them were urban, and some supported left-wing causes, particularly in the 1930s. Many Jews from the northeast were active in the labor movement, the fight for racial integration, and human rights. They were the objects of antisemitic stereotypes that portrayed Jews as misers, unscrupulous in business, and immoral.

Jewish students were treated by University of Minnesota administrators and many of their peers as “different,” “inferior,” or even “dangerous.” Nevertheless, Jewish students were admitted to most of the University’s colleges, including its professional schools, although there were rigid quotas to keep their numbers to a minimum, and medical internships were sometimes made “proportional” to the number of Jews in the state. The nation’s quota system that began in the late 1910s dramatically limited the number of Jewish students who could attend private colleges and many professional schools, which made public universities and colleges a haven for them.For a discussion of quotas in higher education against Jewish students see Jerome Karabel, The Chosen: The Hidden History of Admission and Exclusion at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton (New York: Harper, 2006); Dan A. Oren, Joining the Club: A History of Jews and Yale (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986); James Axtell, The Making of Princeton University: From Woodrow Wilson to the Present (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006); Roger L. Geiger, The History of American Higher Education: Learning and Culture from the Founding to WWII (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016); Harold Weschler, The Qualified Student: A History of Selective College Admission in America (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1977).

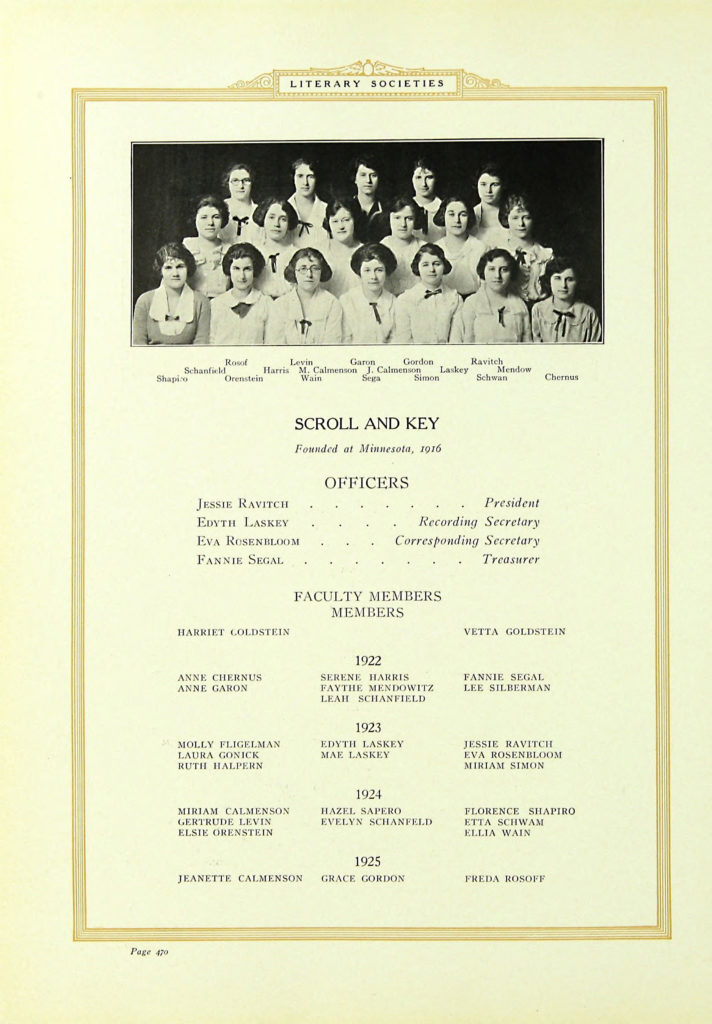

The undergraduate world of the University of Minnesota was built on social fraternities, sororities, and many interest groups that were rigidly separated by religion, race, and gender. The Minnesota Daily, honor societies, some clubs, and political organizations did include Jews, but virtually no African Americans. In this world of parallel organizations, students from marginalized groups often found a sense of security and community by establishing their own separate groups, not the least because they were barred from all others. The Menorah Society, founded for faculty and students in 1903, and then Hillel, founded in 1923, were both national movements to enable Jewish students to connect with one another.

The University of Minnesota had Jewish and African American social fraternities and sororities because both groups were barred from entering what was known as the Greek letter system. Jews also created their own pre-professional organizations for the same reason. The University had chapters of a Jewish engineering fraternity, Sigma Alpha Sigma; dentistry, Alpha Omega; medicine, Phi Delta Epsilon; and pharmacy, Alpha Beta Phi.

This parallel structure reflected the larger society in which Jews and African Americans created their own philanthropic, religious, professional, political, and social organizations because their membership was barred by organizations in the majority culture. But separation also limited opportunities and access to all of University life. At the University, Jews were treated like “white” students in many parts of campus life. But they were categorized as “different” for others.

When students, parents, or members of the Jewish community complained about their exclusion to administrators, their concerns were blamed on employers, householders who ran boarding houses, or students’ intolerance. Jewish students, like African American students, were called to task for having the wrong expectations. Because many of them embraced the same prejudices toward Jews, University administrators rarely took a stand or used their leverage to change policies related to Jewish or African American students until well into the 1950s, and most often not until decades after that.

The Case of Coffman Union: Unwanted Jewish Students

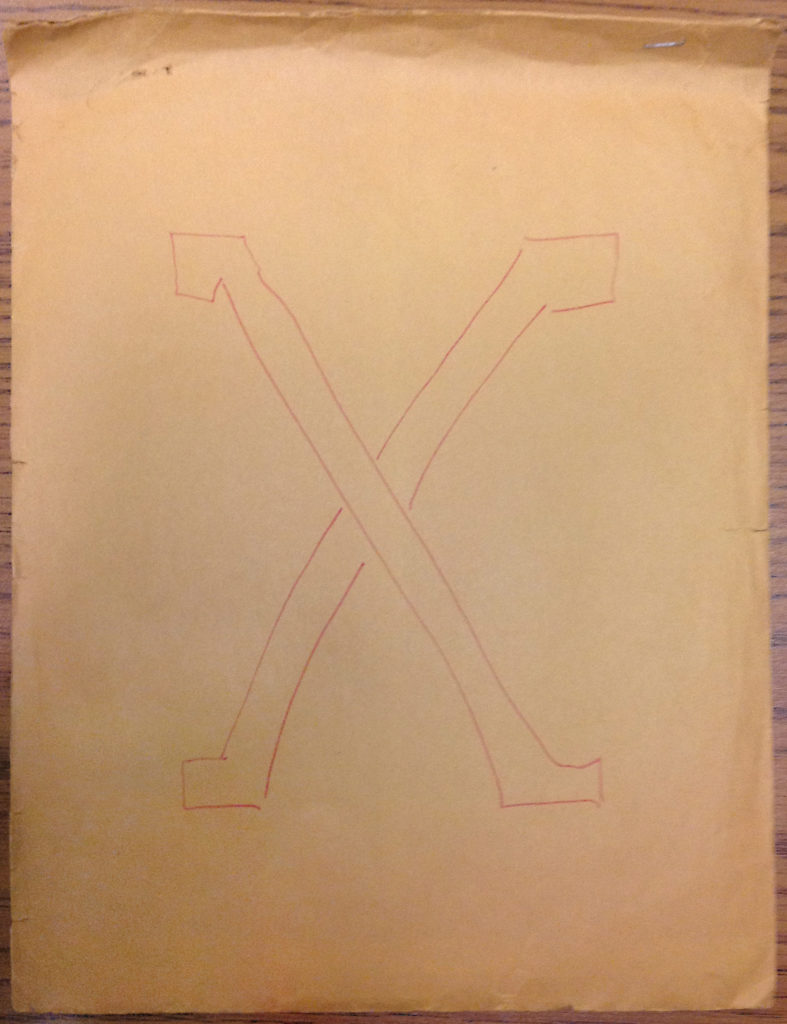

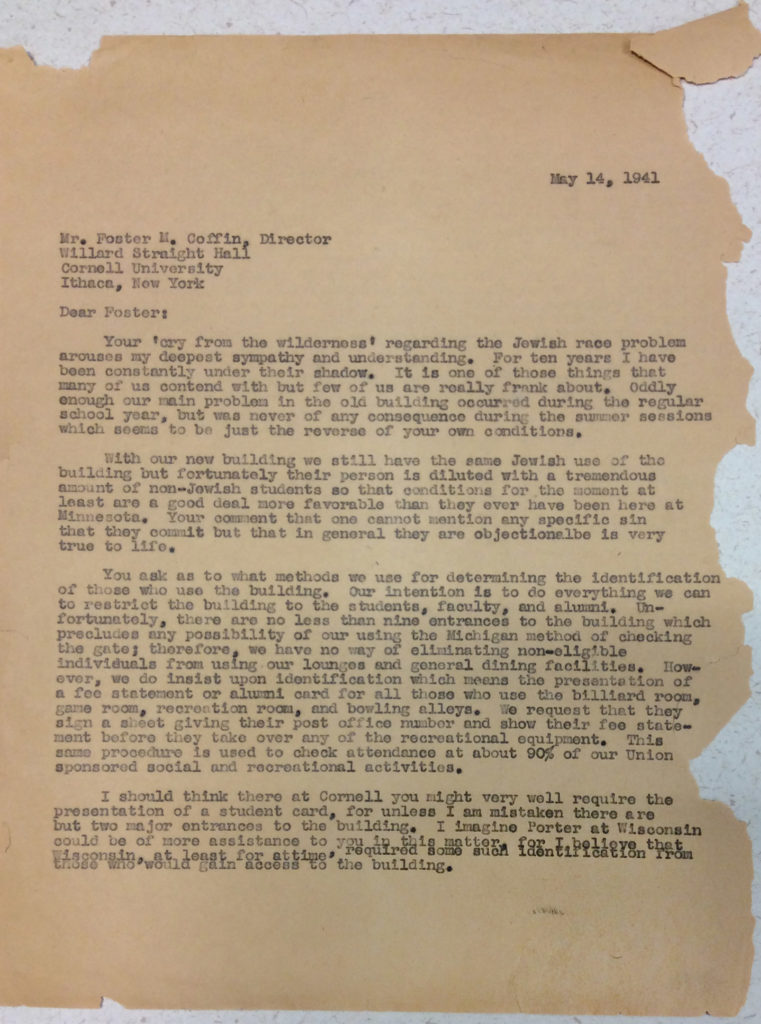

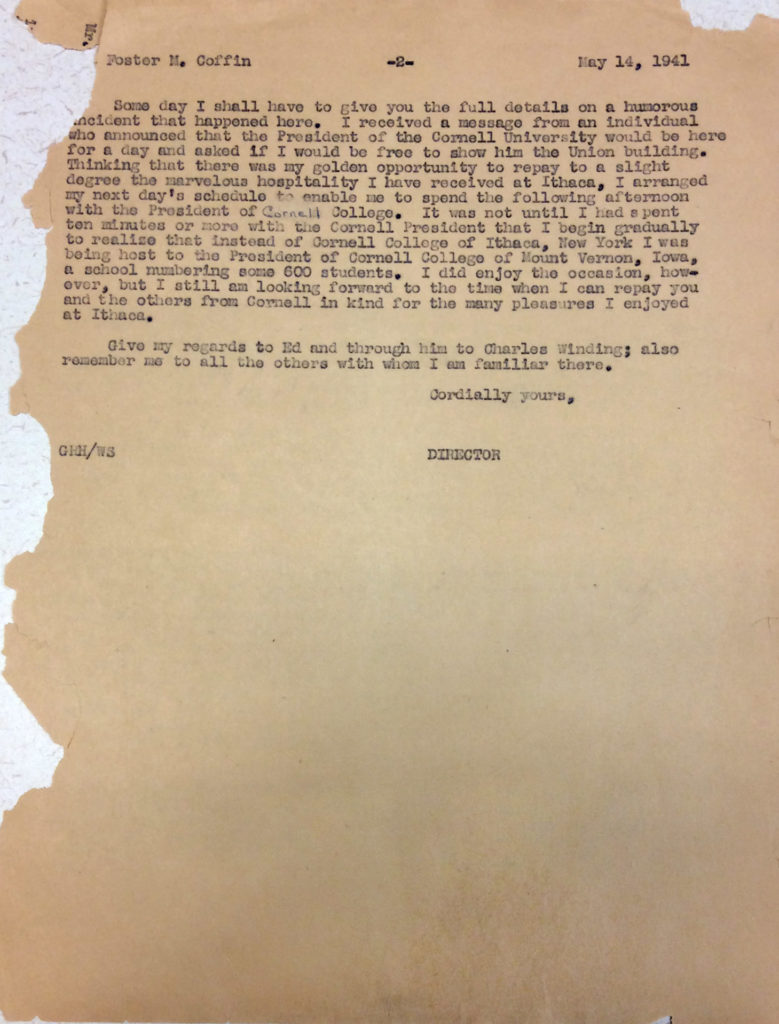

One of the most disturbing expressions of campus antisemitism in this era is visible in a correspondence between the directors of the University of Minnesota’s Student Union and Cornell University’s Union. In the year 2000, the letters were discovered in Coffman Union, hidden within a folder marked “X” in a long-forgotten file cabinet. G. R. Higgins, director of the newly built University of Minnesota Student Union (which would subsequently be named for Lotus Coffman) wrote in 1941 to Cornell University’s student union director Foster Coffin to complain about the “Jewish use of the building.” He remarked about Jewish students that “their person is diluted with a tremendous amount of non-Jewish students.” Jews were rendered as alien and repulsive, only tolerable if they were outnumbered by non-Jewish students. They were racialized by reference to blood (diluted). The director could not find them “committing a specific sin,” but felt burdened by their mere presence. This exchange took place in 1941 when the Nazi ideology focused on racial genocide against Jews was firmly in place. The language of the letter is disturbingly close to that used by the Nazis.This case and others are discussed in Riv-Ellen Prell, “Antisemitism without Quotas at the University of Minnesota in the 1930s and 1940s: Anticommunist Politics, the Surveillance of Jewish Students, and American Antisemitism,” American Jewish History 105, nos. 1/2 (January/April 2021): 157-188.

The Case of Jewish Students and Housing: “Too Many Jews”

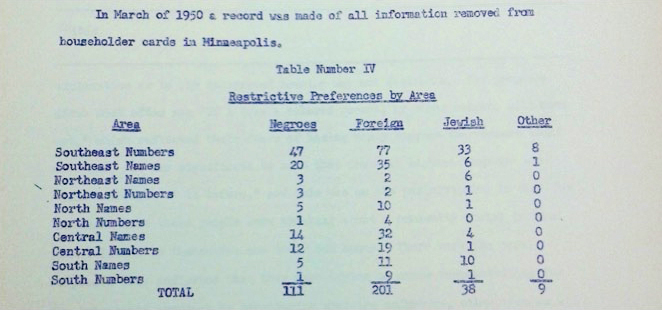

From the 1920s to the 1950s, boarding houses offered rooms and meals to students throughout Minneapolis neighborhoods. Until well into the 1950s, “householders” who ran these homes had the right to reject Jewish, African American, and foreign students. The University, only under pressure from student members of the NAACP in the 1950s, stopped giving householders “preference cards,” which allowed them to refuse boarders on the basis of race, religion, nationality, or ability.

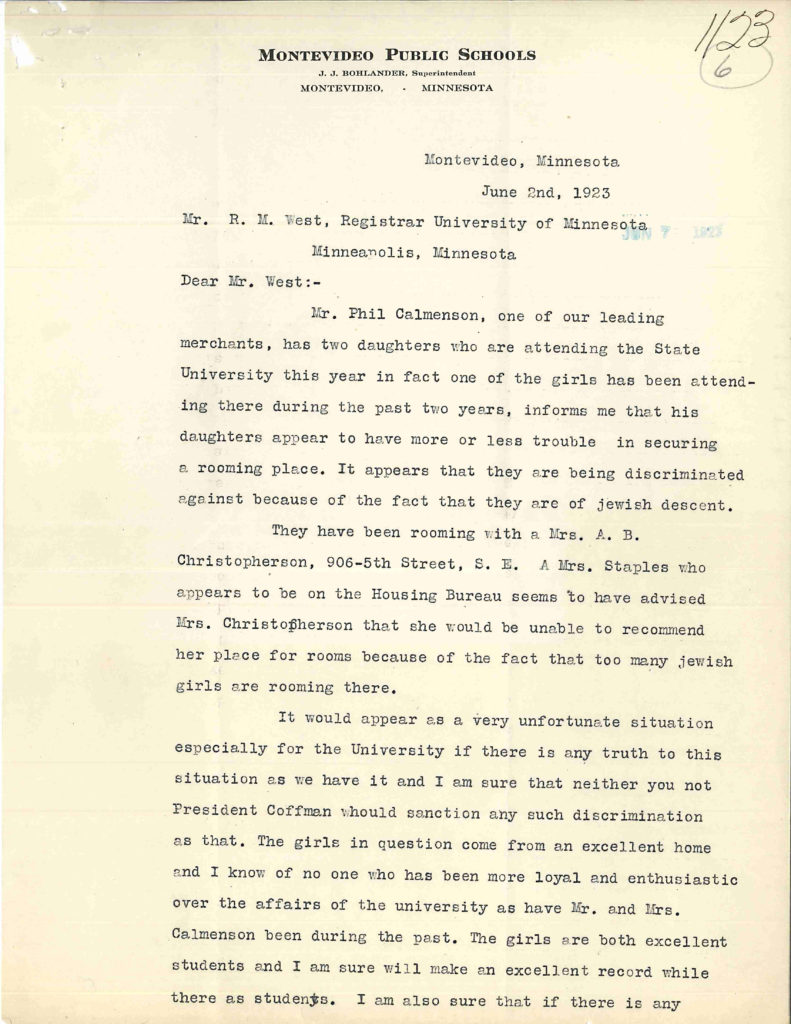

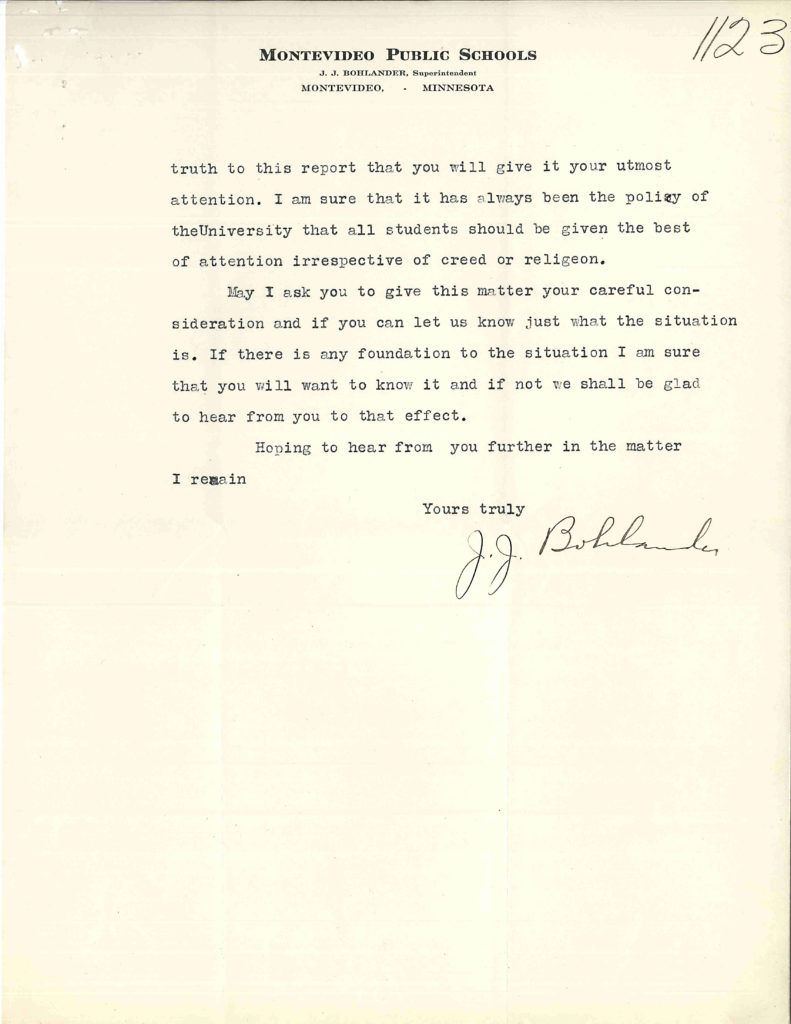

The Calmenson Sisters Could Not Find Housing

In 1923, Miriam and Jeanette Calmenson, the daughters of Phil Calmenson of Montevideo, were excluded from a boarding house near campus because, they were told, they were “of Jewish descent.” Mr. Calmenson felt the need to turn to his local School Superintendent Mr. J. J. Bohlander for help in addressing the problem. He appeared to believe he could not be effective if he contacted the University himself.

Boarding houses were given “rankings” by the University of Minnesota, and Mrs. A.B. Christopherson who ran the one where the Calmensons were roomers worried about her standing. The presence of “too many Jewish girls,” she explained, lowered the ranking, imperilled her ability to succeed financially, and thus justified why they should be excluded. The Director of the Housing Bureau Mary Staples claimed she never said “Jews downgraded a house.” She met with one of the Calmenson sisters and the woman who ran the house but “it did not succeed in clearing it up.”

The Case of Jewish Students Being Invited to “Consider” Leaving the Dental Hygiene Program “For Your Own Good”

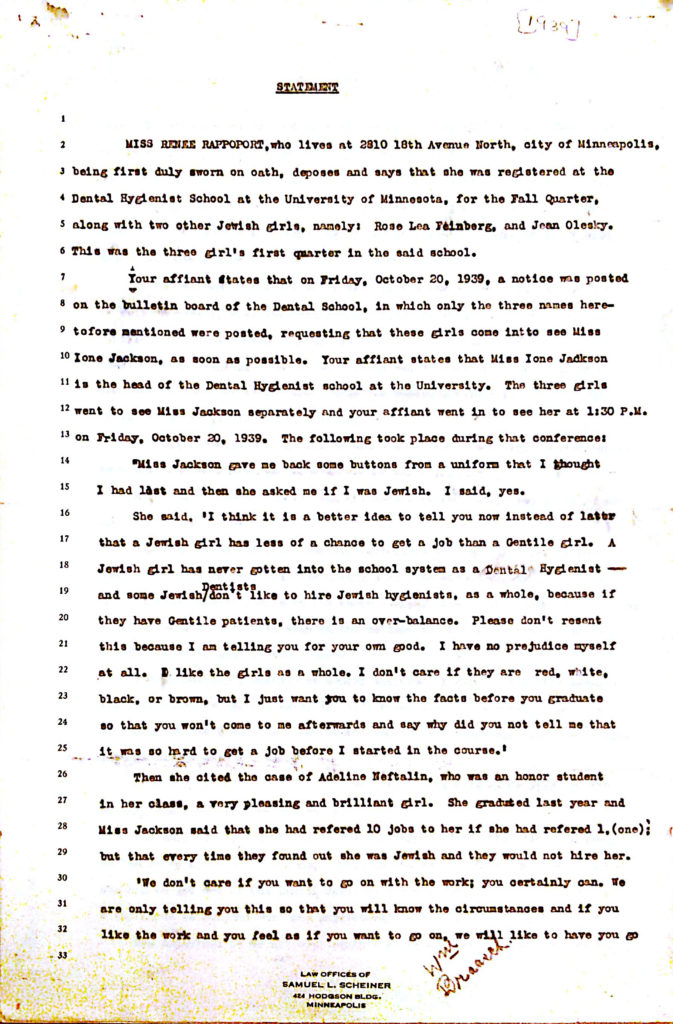

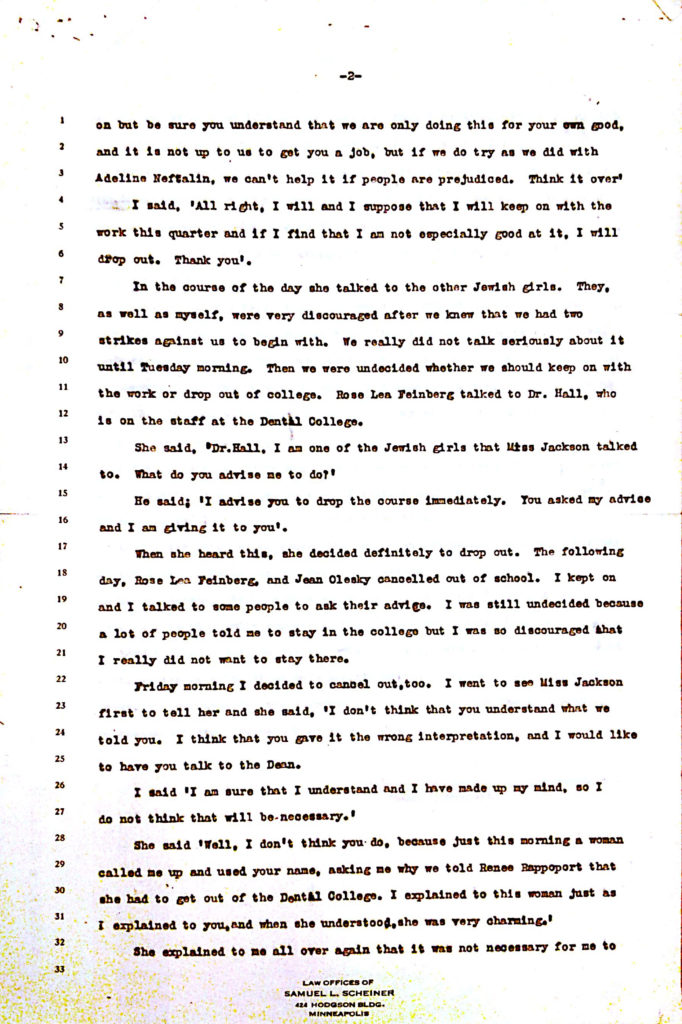

Jews had limited work opportunities in Minnesota because employers had the right by law to exclude applicants on the basis of race, religion, or gender. There is no record that the University made any effort to challenge racism and antisemitism—to urge, for example, dentists to hire Jewish hygienists. Instead, administrators simply warned students about these realities and advised them to consider giving up their studies. That was the case with three young women who were contacted in the fall of 1939 by Ione Jackson, head of the Dental Hygiene Program in the Dental School, and asked to consider leaving the program to which they had been admitted and had already paid tuition. She invited Renee Rappoport, Rose Olesky, and Rosa Lee Feinberg to consider withdrawing after a month in classes on the basis that no dentist would hire a Jewish hygienist.

Renee Rappoport gave a statement at a deposition to Samuel Scheiner about what transpired. Scheiner was Executive Director of the newly formed Minnesota Jewish Council (later renamed Jewish Community Relations Council), which emerged in 1937 and changed in 1938 to combat increasingly aggressive antisemitism in Minnesota. The organization viewed Miss Jackson’s “helpful” suggestion as part of a pattern of discrimination against Jews.Samuel L. Scheiner was a Jewish attorney who headed the first independent, statewide Jewish community relations agency in the United States to organize against antisemitism in Minnesota from 1938 until his retirement in 1974. He was a graduate of the University of Minnesota Law School. In 1938, Jewish leaders in the Twin Cities and Duluth formed the Anti-Defamation Council of Minnesota in response to a rise in public antisemitism which had been increasing throughout the United States since the 1920s. The 1938 Minnesota Governor’s election tipped the balance, however, when Farmer-Labor candidate Elmer Benson, who had Jewish staff members, was specifically attacked for his Jewish connections. Once formed, the organization investigated the pro-fascist, antisemitic climate in the state. Click here for more information on Scheiner.

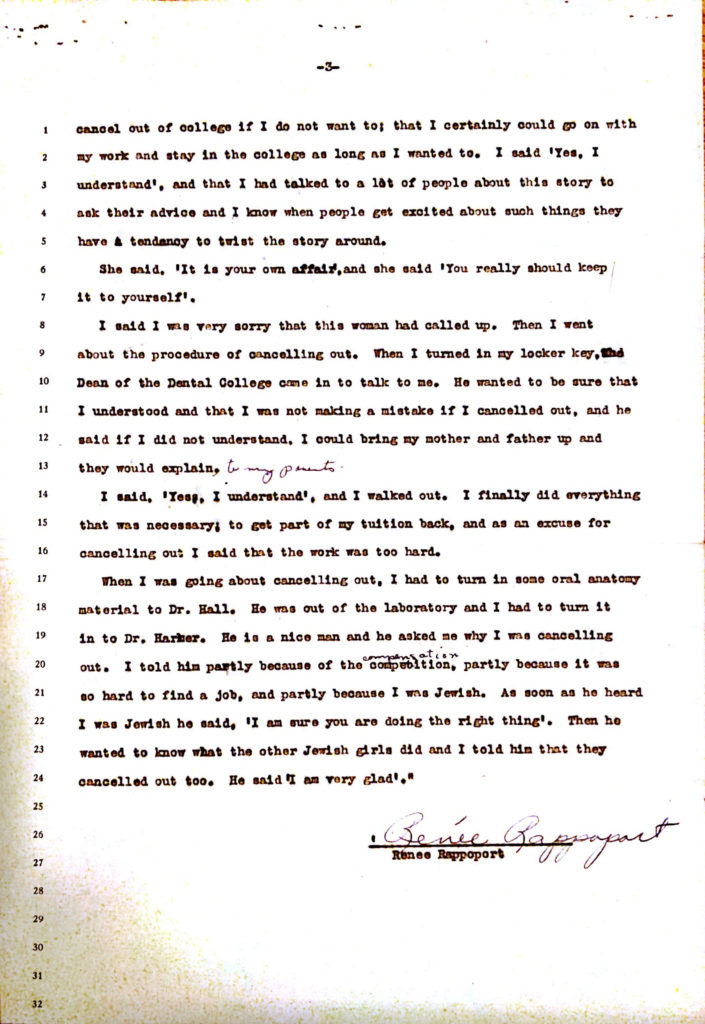

In fact, much of the deposition focused on what happened after Rappoport’s discussion with Miss Jackson. She was castigated for speaking with others in her community. She was advised to “keep it to herself” when she explained that she sought the counsel of many people in her community. She was assured by the Dental School dean that she did not need to leave only after he received a call expressing concern about a Jewish young woman being told to consider leaving a program to which she had just been admitted.

However, when Rappoport spoke to her oral anatomy professor who inquired why she was leaving he told her, “I am sure you are doing the right thing,” when he learned she was Jewish.

These events were deeply disturbing to the newly formed Council, which came into existence in response to the overt antisemitism embraced by the Silver Shirts and other fascist and right-wing groups that were popular in Minnesota. In addition, the 1938 Governor’s race that is detailed in the essay “Political Surveillance of the University” was viewed by the Jewish community and many Farmer-Labor followers as unapologetically antisemitic. The Council was sufficiently disturbed that Scheiner called a special meeting on November 2, 1939 to discuss the matter. Along with Mr. Scheiner, nine leaders of the Jewish community were present, including several physicians on the University’s faculty, business people, and academics. They assigned a group of their members to meet with the families of the girls who were invited to consider leaving the program and formed another committee to meet with Dean of the Dental School William F. Lasby and Miss Ione Jackson.Among those who attended the November 2 meeting were: Arthur Brin, a businessman active in community affairs; Dr. Moses Barron, a clinical Professor of Medicine at the University of Minnesota, where he received a medical degree in 1911, and would become in 1951 Mount Sinai Hospital’s first Chief of Medicine; and Dr. Leo Rigler, who received an MD from the University of Minnesota and became the first Chief of Radiology at the University of Minnesota in 1933 and held the position until 1957. Minutes of Jewish Community Relations Council of Minnesota Special Meeting, November 2, 1939, Box 16, General Discrimination 1939, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, MN.

“It was suggested that this committee attempt to straighten out Miss Jackson in her cold-blooded and blunt attack on matters of this kind. The group felt that these talks should be had with the prospective students prior to their spending a month in the school, for they lose part of their tuition and it is very undesirable as far as the students are concerned.”Minutes of Jewish Community Relations Council of Minnesota Special Meeting, November 2, 1939, Box 16, General Discrimination 1939, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, MN.

Arthur Brin stated that another committee “ought to call on President Guy Stanton Ford.” He was invited to appoint the members of that committee. Brin noted that this encounter with Ione Jackson was “only one of many incidents throughout the entire University.”Minutes of Jewish Community Relations Council of Minnesota Special Meeting, November 2, 1939, Box 16, General Discrimination 1939, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, MN.

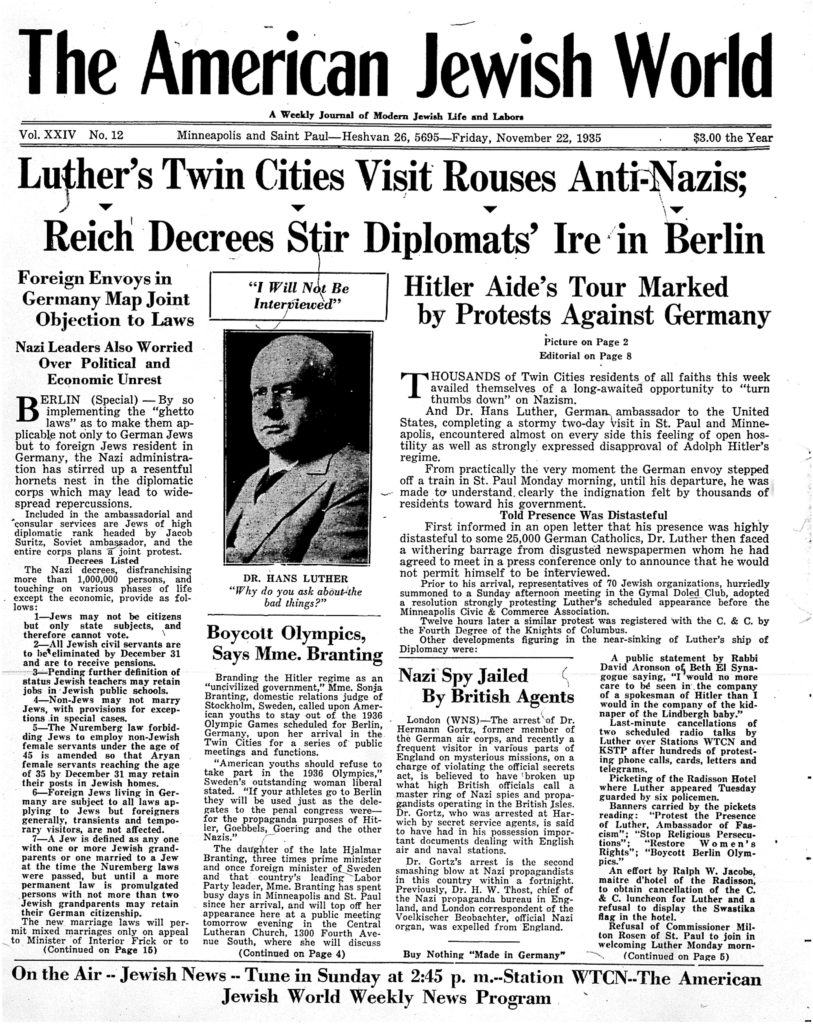

On November 3, 1939, The American Jewish World featured an editorial entitled “The Duty of the University.” Rabbi David Aronson referred to a three-day institute held at the University that raised the question of whether educational institutions “owe any implied duty to assist those they have trained” who cannot find employment. Rabbi Aronson wrote in his editorial what the Institute did not choose to explore. He raised the question of the University’s responsibility to address and not ignore “the question of discrimination practiced by many employers…because of their religious affiliation or antecedents.” He wrote,

[T]he educational institutions are decidedly remiss in their duties if they make no concerted effort to reduce such discrimination in the minds of those who contact the university in regard to employing its graduates… If the Dental School, for example, would not only teach its students the mechanics of dentistry but would imbue them with the true scientific spirit, the dentists employing a dental hygienist would look for the person who was best trained in the profession without the irrelevant references to the applicant’s religious affiliation.David Aronson, “The Duty of the University,” American Jewish World, November 3, 1939, https://umedia.lib.umn.edu/item/p16022coll529:68328. The same issue also featured an article about the young women leaving the program titled “4 Dental Hygiene Students Quit U, Bare Job Prejudice.”

The editorial also raised these issues about the law school.

The dental hygiene case underlines the complexity of life for Jews in Minnesota in general and the University of Minnesota in particular in the 1930s, during a highpoint of antisemitism in the state and the nation. Why were leaders of the Jewish community concerned by what the University did when the problem appeared to be outside of the institution? Distinguished Jewish faculty members of the School of Medicine and Jewish business leaders who attended the November meeting wanted the University to stand up against antisemitism in employment, just as African Americans called on the University to stand against racism. They wanted Jews to have employment opportunities.

Their deep concerns about the University’s actions in 1939 also need to be set in a global context. As they were fighting home-front antisemitism, Minnesota Jews, like Jews throughout the United States, were closely following Hitler’s rise to power and the vulnerability of European Jews. Antisemitism was a constant for Jews everywhere at this point in history.

Neither the administration of the University nor of the School of Dentistry wanted to be perceived as prejudiced against Jews. Indeed, Dean and Assistant to the President Malcolm Willey informed President Guy Stanton Ford that he had heard rumors that three students were “objects of anti-Jewish discrimination.” Willey further noted that a “downtown lawyer” had been consulted, and “members of the staff (Rigler, Barron, Marget and Cooper) have some knowledge of the situation.” His follow-up memo stated: “It is my understanding that the groups first concerned in protesting now understand the helpful and wholly unprejudiced attitude of Miss Jackson and are satisfied.”Malcolm Willey to Guy Stanton Ford, Confidential Office Memorandum, November 7, 1939, Office of the President, Box 16, Jews 1923-1939, University of Minnesota Archives.

The concerns of the Minnesota Jewish families and leaders who were involved in this case were not “satisfied.” The University was concerned about being perceived as antisemitic, not about whether it was. Willey chose to misread a Jewish communal response that was in no way grateful to Jackson, the School of Dentistry, or the University of Minnesota.

These sources suggest that the “choices” given to Jewish women students—to stay or to leave dental hygiene—really were not choices at all. Although told that she was given a choice to stay or to leave, Renee Rappoport, like the other students, left because she felt that she had no real choice. These students were admitted to a program at the University of Minnesota, as they were to discover, that led to no employment.

What did the University do to fight antisemitism and racism in the preparation of lawyers, doctors, and dentists? If asked, the University blamed the professionals for their attitudes. Similarly, if asked, the professionals blamed their clients and patients for their inability to hire Jews or African Americans. Yet again, no one appeared to be held accountable for the fact that Jewish women would not be hired. Nevertheless the School of Dentistry continued to admit Jewish women. Upon learning that they were Jewish, administrators then counseled them to “choose” whether or not they wanted to continue their studies, knowing they would not receive a position. The constant shifting of blame for the exclusion of Jewish students dominated life at the University of Minnesota. At the same time, Jewish Minnesotans were grateful to the University that their children could study there, even if professional schools continued to enforce quotas against Jews.Minutes of Jewish Community Relations Council of Minnesota Special Meeting, November 2, 1939, Box 16, General Discrimination 1939, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, MN. Issues of employment and discrimination for Jews in Minneapolis and St. Paul are discussed in Laura Weber, “Gentiles Preferred: Minneapolis Jews and Employment,” Minnesota History 51, no. 5 (Spring 1991): 167-182.

Nazism Arrives at the University of Minnesota with the Third Reich’s Ambassador Hans Luther

In the fall of 1935, the University of Minnesota welcomed the Nazi Ambassador to the United States Hans Luther. Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany in the 1930 election in the midst of economic depression. A politically chaotic time followed with competition for the chancellorship, which Hitler assumed in 1932, and the dissolution of the Reichstag, the democratically elected national assembly. The Nazi platform was based on unifying a German nation that was racially pure. Jews were its enemy.“The Rise of the Nazi Party,” A Teacher’s Guide to the Holocaust, Florida Center for Instructional Technology, updated April 2, 2019, http://fcit.usf.edu/holocaust/TIMELINE/nazirise.HTM.

The United States Congress passed Neutrality Acts just a few months prior to Ambassador Luther’s November visit and again in 1937 which prohibited exporting weapons. Long-standing allies England and France were endangered by fascist nations which included Germany, Italy, and Spain. American neutrality meant that fascism would grow unhindered. Few Americans following WWI wanted to engage in war again. Many Americans supported Adolf Hitler and Nazi policies of racial hierarchy and anti-communism.

Hans Luther was appointed Ambassador to Washington in 1933. In all of his public statements and speeches he insisted that there was no religious discrimination in Nazi Germany, no persecution of dissidents, and “internal matters” in Germany should be of no concern to others.

Hans Luther Visits the Midwest

The University of Minnesota genially hosted Ambassador Luther on November 19, 1935 as part of his tour of midwestern cities and universities intended to counter a national campaign to boycott the Berlin Olympics scheduled for the summer of 1936. Many Americans questioned whether the United States’ participation in the Olympics would appear as an approval of Nazi policies, particularly around race and religion and the Third Reich’s treatment of political dissidents. Luther went to the midwest because of the strong German heritage of its citizens. He expected sympathetic treatment on campus and in community organizations. His first stop in Madison, Wisconsin proved that he had misjudged the popularity of Nazism.

In September 1935, just months before Hans Luther’s campus visit, the newly constituted Nazi Reichstag passed the Nuremberg Laws which stripped all German Jews of their citizenship and outlawed marriage and sexual relationships between Jews and Christians in order to create a “racially pure” Germany.

By the time Luther made his midwest tour, Germany had also:

- Directed a purge of Jewish students from universities and cultural organizations

- Fired Jews from newspapers and civil service positions

- Called on Germans to boycott Jewish shops

- Denied Jews health insurance

- Undertook a massive book burning of volumes authored by Jews and other intellectuals deemed as alien to German purity.For more basic information about the Holocaust see “Introduction to the Holocaust,” Holocaust Encyclopedia, The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, https://www.ushmm.org/m/pdfs/20010322-historyofholocaust.pdf.

Who Welcomed Hans Luther and Who Protested?

The University of Minnesota provided one of the most amiable venues Hans Luther encountered. He was the guest of the Twin Cities’ Civic and Commerce Club, though some of its members objected to his visit, and the German Language Clubs that were popular in the Twin Cities. The University’s German Department hosted the Ambassador for a tea in Shevlin Hall.

Hans Luther was greeted with a mass protest against him and Germany at the University of Wisconsin. That was not the case just a few days later at the University of Minnesota, Rather, only fifty students protested Luther’s visit when they went to the University’s Shevlin Hall with the intention of questioning him about Nazi policies. Luther refused to answer questions from the press or from the students. Dean of Women Anne Blitz held students at bay, refusing to let them join the event, and called campus police to eject a student who would not leave.

Protesters Greeted Luther Off Campus

The Berlin Olympic Boycott

Many students demanded that the United States boycott the 1936 Olympics because of Nazi policies. This was an international movement which initially had strong support in the United States.“The Movement to Boycott the Berlin Olympics of 1936,” Holocaust Encyclopedia, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, accessed on July 27, 2023, https://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10007087.

The University YMCA hosted a gathering of thirty students representing fifteen campus religious and political organizations and fraternities. They approved a petition calling for a boycott and intended to put it to a student vote. Their petition read:

Whereas we believe that the spirit of the Olympic games has been violated by Germany’s discrimination in its choice of athletes to represent her, we ask that the 1936 Olympiad be removed from Germany, or that the United States send no official teams.“Anti-Olympic Move Stirs U of M Campus,“ American Jewish World, November 29, 1935.

The boycott group prepared a letter to all students to invite them to vote for or against the petition to boycott the Berlin Olympics. Their mail was refused by the University’s postmaster. When they stated that they would send first class mail, Mr. Poucher informed them it would not matter. Dean of Student Affairs Edward E. Nicholson supported the decision explaining that the Board of Regents had a policy that mail that lacked “general student interest” would be rejected.“P.O. Rejects Boycott Mail,” Minnesota Daily, November 26, 1935.

In fact, seventeen organizations supported the boycott including social fraternities and sororities, Catholic and Jewish student organizations, the M Club of male athletes who excelled at sports, the students taking girl’s physical education, the Farmer-Labor Club, and the Progressive Club. However, equally important were the groups that opposed the call for boycott. The Minnesota Daily editorialized against it and published letters on both sides. There was tremendous interest in this issue on campus, in the state, nation, and world.

The policy that Nicholson urged on the Board of Regents as part of his campaign to limit student rights and to reject any political matter that he deemed propaganda silenced the opportunity for students to speak out against or debate antisemitism and fascism. In his role as Dean of Student Affairs he was bothered as much by students from Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish organizations creating a democratic vote by students on the urgent question of responding to Nazism as he was by “communism.”

The Link Between Jews and “Reds” at the University of Minnesota

The myth of the “Bolshevik Jew” crossed the Atlantic to the United States after the success of the Russian Revolution in 1917 when the Bolsheviks seized power. That victory gripped the government of the United States in fear during WWI and at the height of the first “Red Scare” from 1919-1920. Attacks on Americans’ civil liberties and their right to dissent fell especially hard on labor activists, political dissidents, and those who fought for civil liberties of all kinds. Jewish immigrants from Russia and Italian immigrants were particularly targeted. The environment of fear and repression was created by politicians, laws, vigilantes, and a newly powerful FBI. It involved unprecedented persecution of Jews and overt antisemitism in the United States.Beverly Gage, Gman: J Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century (New York: Viking Press, 2022); Adam Hochschild, American Midnight:The Great War, A Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (New York: Mariner Books, 2022).

Jews’ involvement in the labor movement and in radical organizations made this immigrant group (together with many other immigrant groups) a constant FBI target, which often led to the deportation of Jews without due process. “Jew” was a racial category in this period, sometimes a political and economic one as well in the United States, but by no means solely or even necessarily a religious one. Anti-immigration debates that dominated this period consistently emphasized Jews as not only a race, but as racial “others” who would undermine and pollute “true Americans.”Leonard Dinnerstein, Anti-Semitism in America (New York: Oxford, 1994) 77-104.

These issues were part of the political landscape of Minneapolis and St. Paul as well. A minority of Russian Jewish immigrants were involved in communist, labor, and left-wing organizations in Minnesota, but they were often all painted with the same red paint brush. Politically conservative groups, leaders, and anti-union forces insisted that any support for workers’ rights amounted to communism.

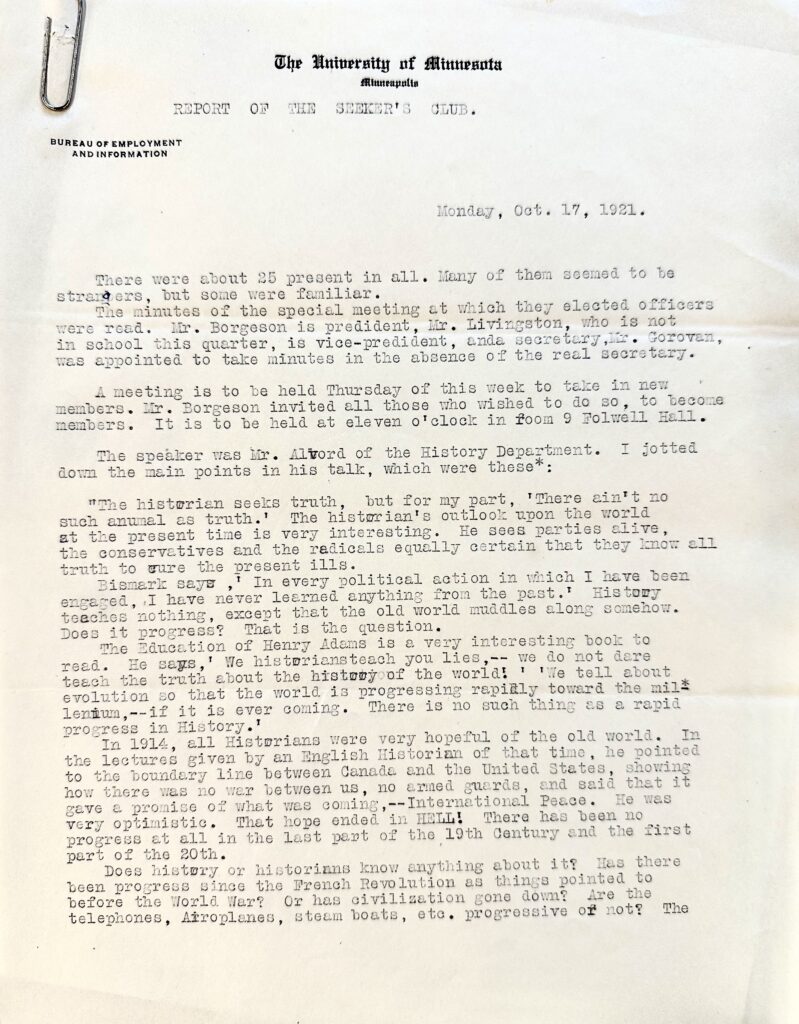

This form of antisemitism landed on the campus of the University of Minnesota when undergraduate students organized the Seekers Club whose purpose was to discuss major political issues of the period such as the American economy and totalitarianism.Robert Cohen examines this early period of the American student movement in his When the Old Left Was Young: Student Radicals and America’s First Mass Student Movement 1929-1941 (Oxford University Press, 1997) 31-32.

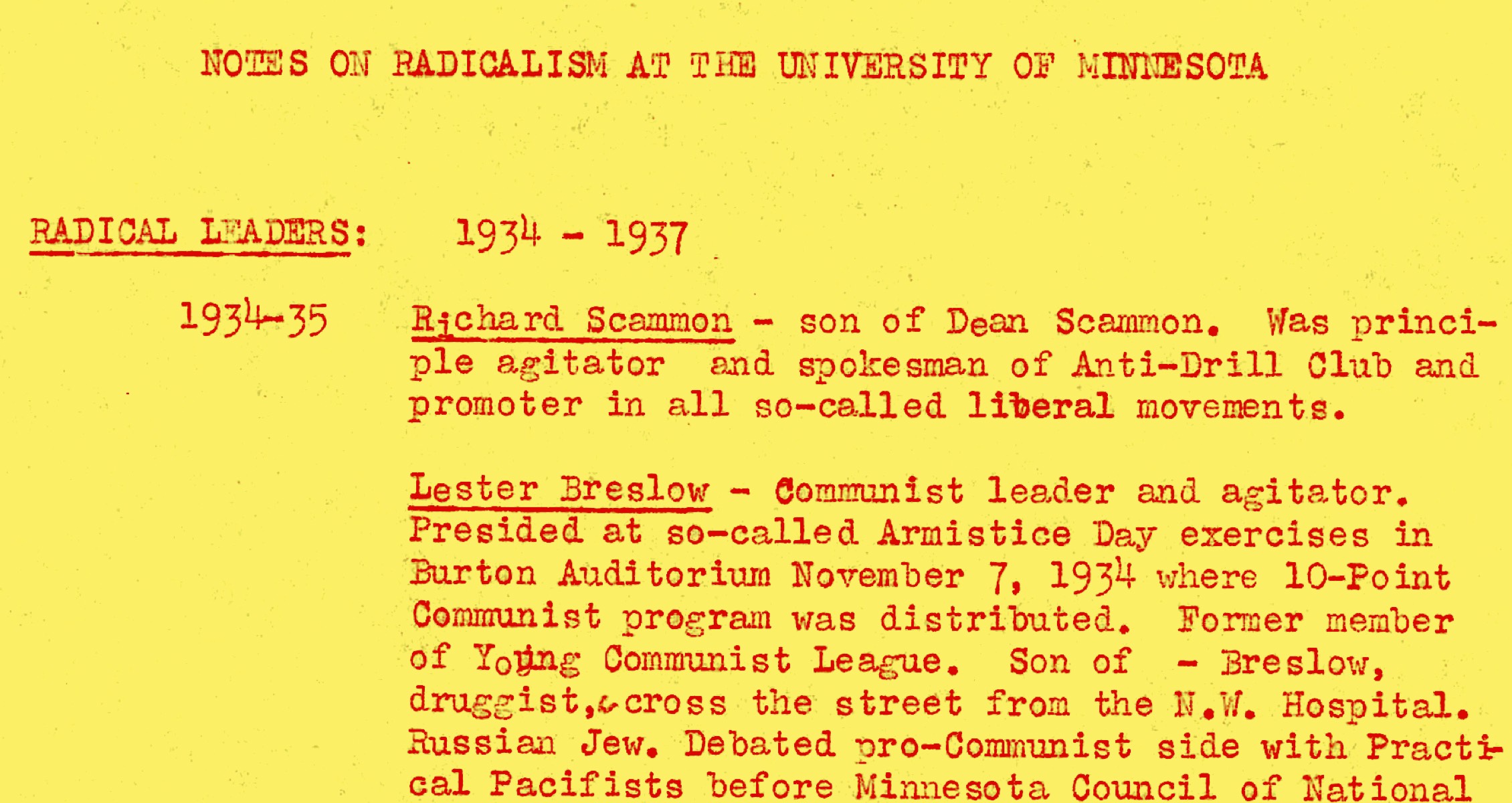

Faculty members frequently delivered the lectures to students at weekly meetings. Groups like the Seekers Club were common on college campuses during this era. In 1920, during the Red Scare, Dean Nicholson granted the organizers permission to create the club that met in Folwell Hall on the campus. In 1920 and early 1921 the club attracted a few hundred members, but the membership dwindled to a few dozen followers during the second year. Dean Nicholson’s suggested in various memos that student radicalism began on the campus with the founding of this group. He described the two students who met with him to gain permission to start the Club as “Jews,” and that they were from New York. His memo noted their identities as a shorthand for their “radical” politics.

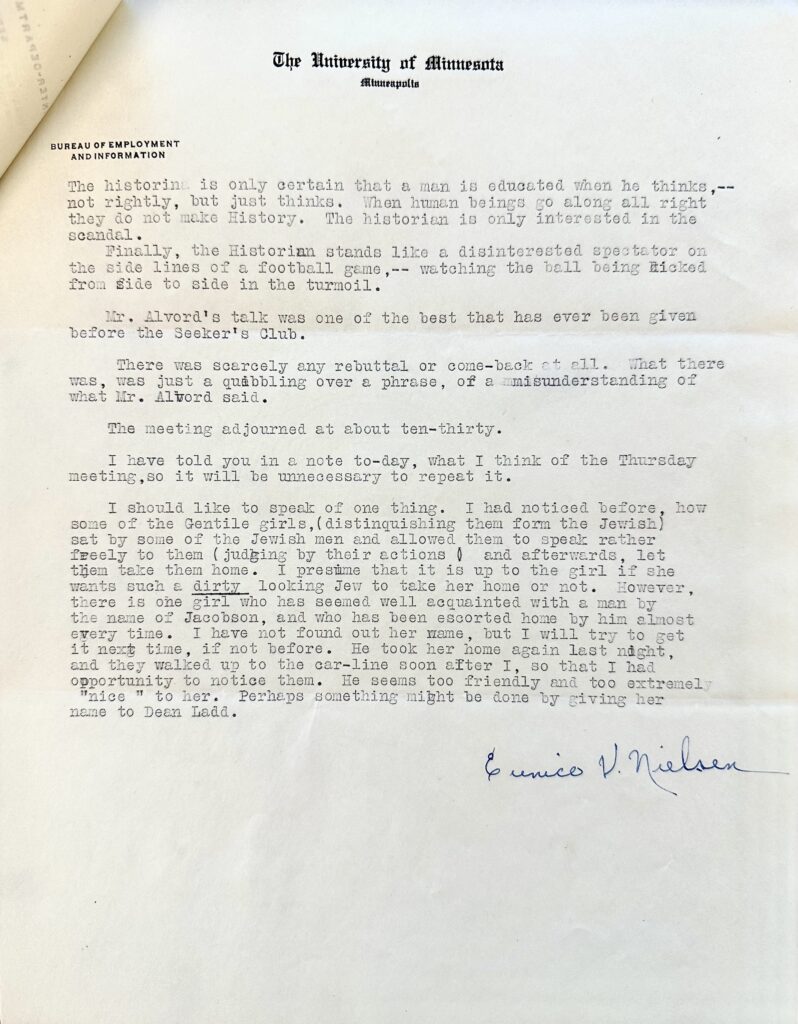

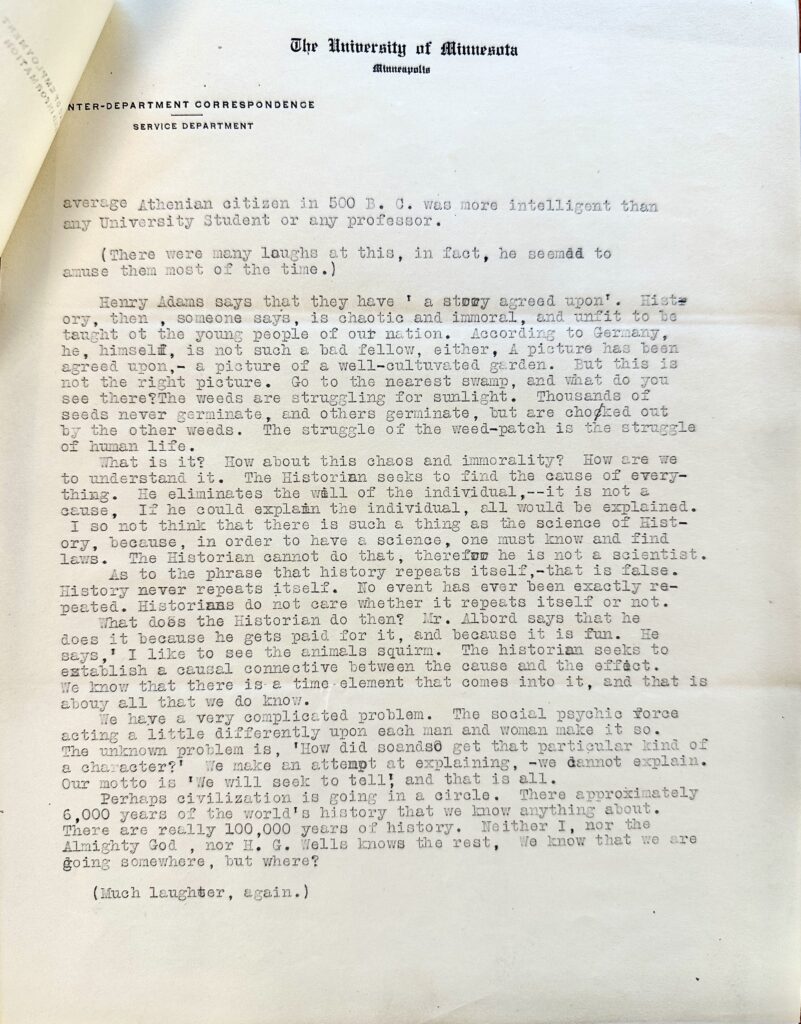

Unbeknownst to the students who started the club or who attended it, they were under regular surveillance. Dean Nicholson received weekly reports about Club meetings that documented who was present and what was discussed. His spies were employees in his office. The reports noted who or how many Jews attended, and labeled some as “Russian Jews,” meaning immigrants. Eunice V. Nielsen, an employee of the Service Department who reported to Dean Nicholson, wrote most of the reports on “inter-office” official stationery. She sent them directly to Dean Nicholson and commented constantly on the presence of Jews in the group. Not only did she count them and name them, but she also commented on their appearances. In one report she caricatured the accent of Bessie Kasherman for paragraphs, explaining that “tone and inflection of the voice plays an extremely important part in giving the meaning of what one is saying.” She never explained what that meaning was.Eunice V. Nielsen to Dean of Student Affairs Edward Nicholson, Report on the Seekers Club, May 9, 1921, Box 14, 1920-1921 Seekers Club, University of Minnesota Archives, Minneapolis, MN.

The following October, Nielsen grew increasingly anxious about the interactions between what she described as “Gentile girls” (not Jewish, she explained) who sat by “Jewish men and allowed them to speak rather freely to them.” She noted that some of those girls let “them” take them home. Miss Nielsen opined that it is up to the girl “if she wants such a dirty [she underlined the word] looking Jew to take her home.” Another girl she observed was waiting at the same time as she was at the “car-line.” A man named “Jacobson” (an obviously Jewish name) “seems too friendly and too extremely ‘nice’ to her.” Nicholson’s spy recommended giving the girl’s name to Dean Ladd (Tessie S. Ladd was acting Dean of Women).Eunice V. Nielsen to Dean of Student Affairs Edward Nicholson, Report on the Seekers Club, October 17, 1921, Box 14, 1920-1921 Seekers Club, University of Minnesota Archives, Minneapolis, MN.

Nielsen explained to Nicholson and his assistant Mr. Poucher in the same report that she could not attend the next meeting where people would sign up to be members. Her mother considered it “too big a risk…since there are such a large number of Jews that are members.” Nielsen suggested academic students or faculty should take over spying.

One of the last spy reports on the Seekers was filed the next month by a man. He concluded: “Attendance: Thirty. Majority Jewish, foreign accents. One colored man.”James P. Patterson to J.C. Poucher, Report on the Seekers Club, November 8, 1921, Box 14, 1920-1921 Seekers Club, University of Minnesota Archives, Minneapolis, MN.

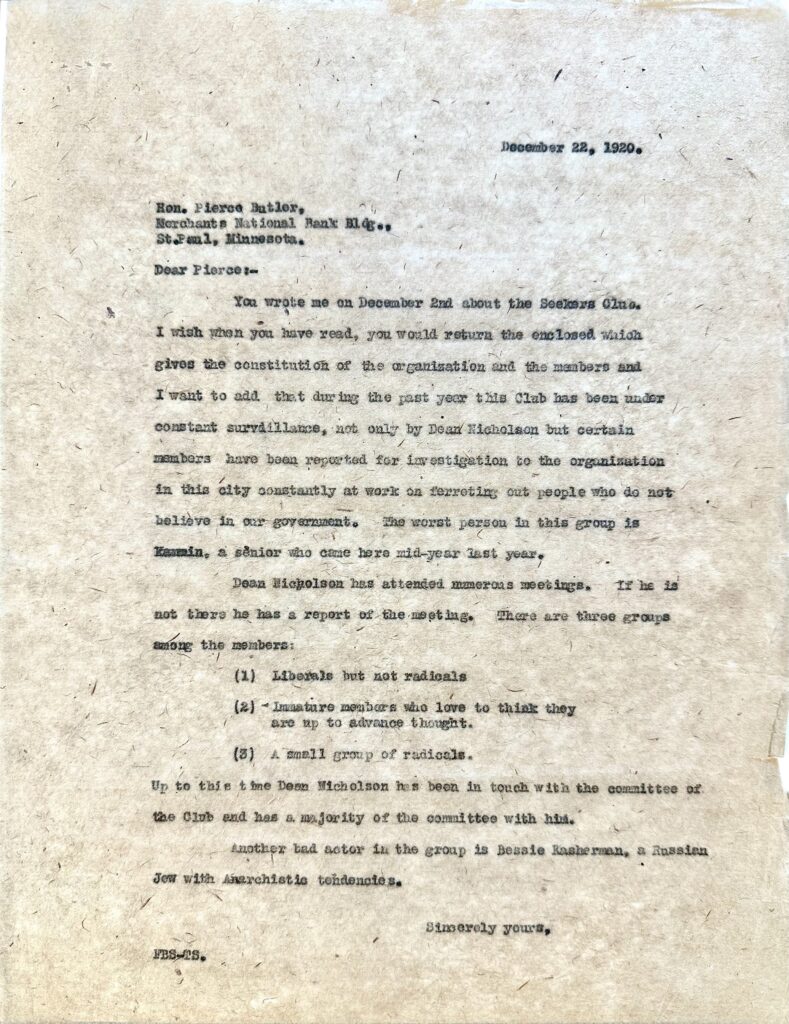

Dean Nicholson valued these weekly reports that obsessively detailed the presence of Jewish students and that, like him, conflated Jewish, Russian Jew, and communist (despite a range of perspectives in the group). The obvious antisemitism of these reports extended to dating habits. Nicholson communicated information about the Seekers Club to people in power. He appeared to be in regular communication about the Seekers Club with Fred B. Snyder, chair of the Board of Regents. Snyder was a Republican politician who served in many political offices and was a founder of the Civic and Commerce Association and active in its many related organizations. In turn, he shared information with Pierce Butler, also a regent, who was soon to become an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court and one of its primary conservatives. Snyder praised Nicholson for putting the group “under constant surveillance.” Snyder named two students as the “worst,” noting that one is “a Russian Jew with anarchistic tendencies.” Nicholson also sent a report on the Seekers Club to President Coffman. The web of surveillance organizations in Minneapolis is discussed in the essay Political Surveillance of the University on this website. Edward Nicholson played a role in these organizations.

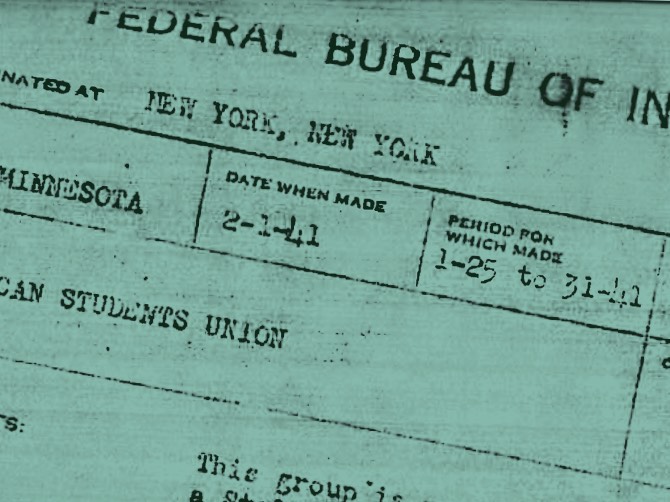

Throughout the 1930s until his retirement in 1941, Edward Nicholson followed the same pattern of spying on student political groups that he had authorized and passing the names of activists to political operatives in the Twin Cities who went on to share their names with other groups that included the FBI and the Citizens Alliance. Many of those activists were Jewish, which was one of the primary reasons these groups were seen as dangerous.

Conclusion

The University of Minnesota was a complicated environment for Jewish students. It afforded them opportunities for higher education, which were far more limited in private colleges, particularly in the Ivy League schools. They were, however, constantly conscious of their Jewishness in matters of housing, social and professional organizations, and social interactions.

In this period of virulent antisemitism in Minnesota, the United States, and Europe, their sense of belonging and opportunity grew far more precarious. In particular, Jewish students involved in left-wing activism were especially targeted on and off the campus for their ideas and their Jewishness.