Political Surveillance of the University

The first American student political movement developed on college and university campuses throughout the United States in the 1930s, including at the University of Minnesota. Robert Cohen, When the Old Left Was Young: Student Radicals and America’s First Mass Student Movement 1929-1941 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993).

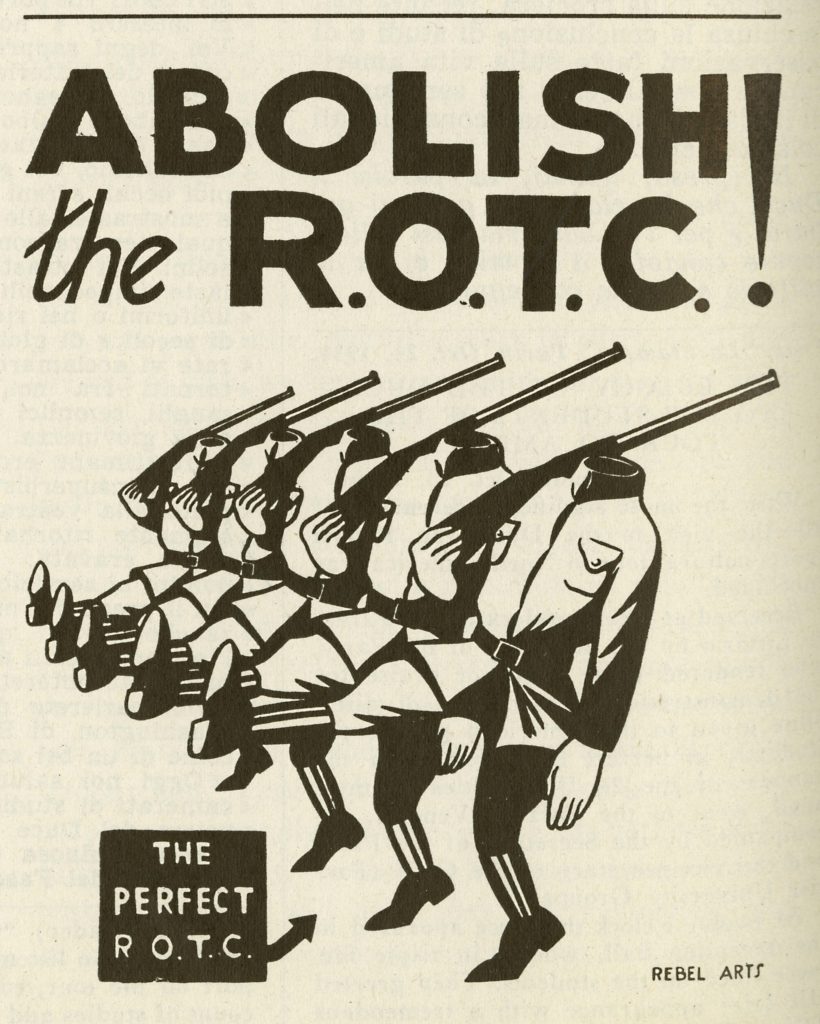

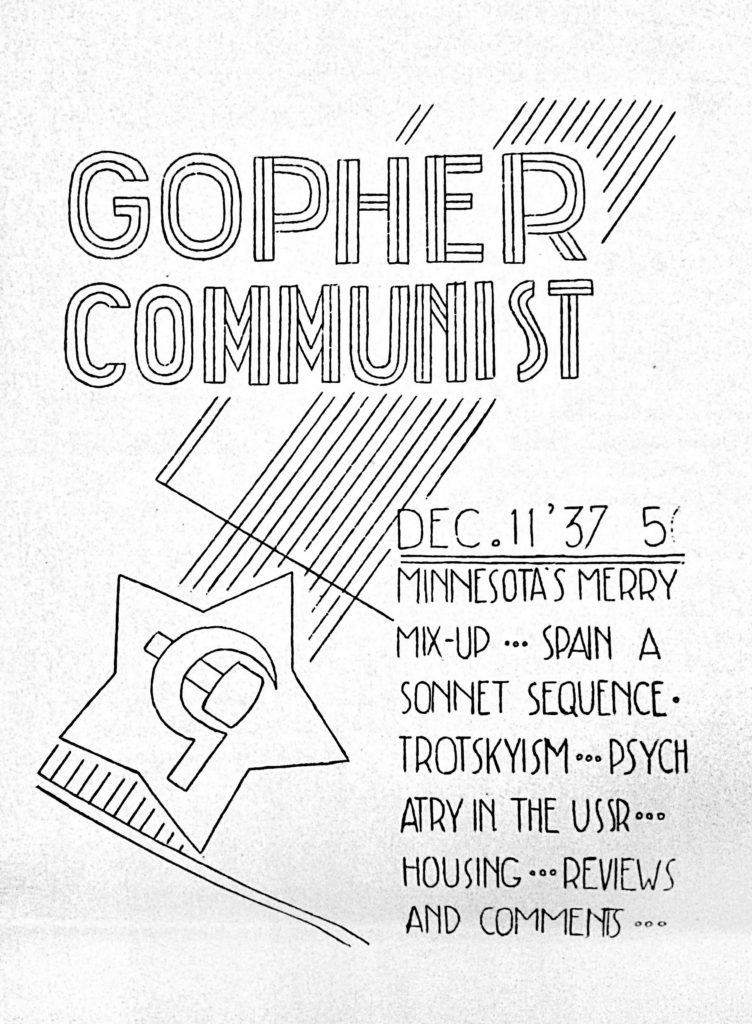

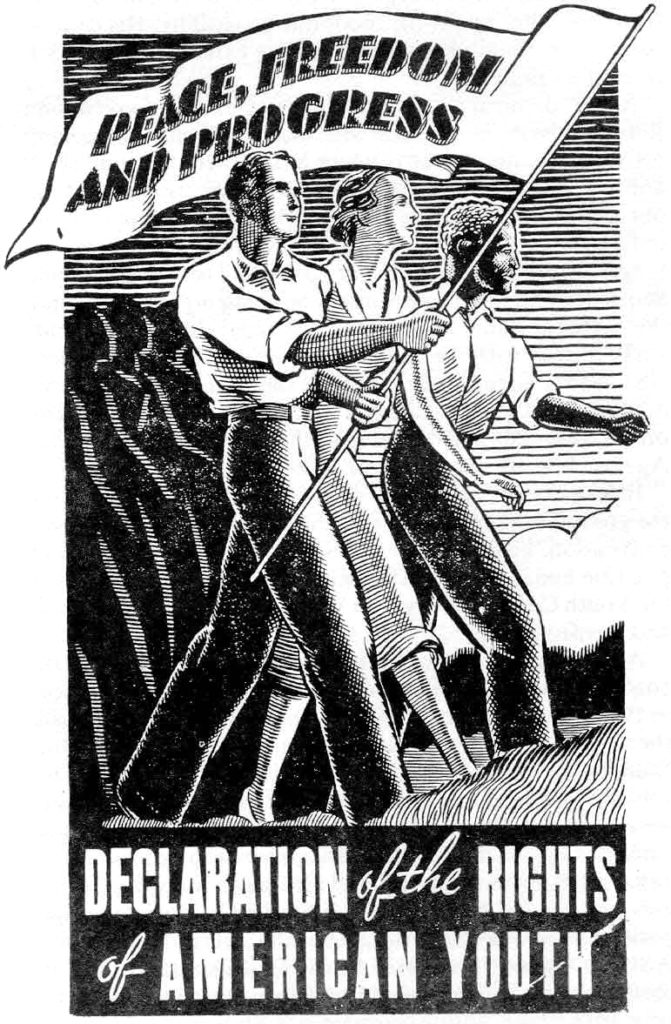

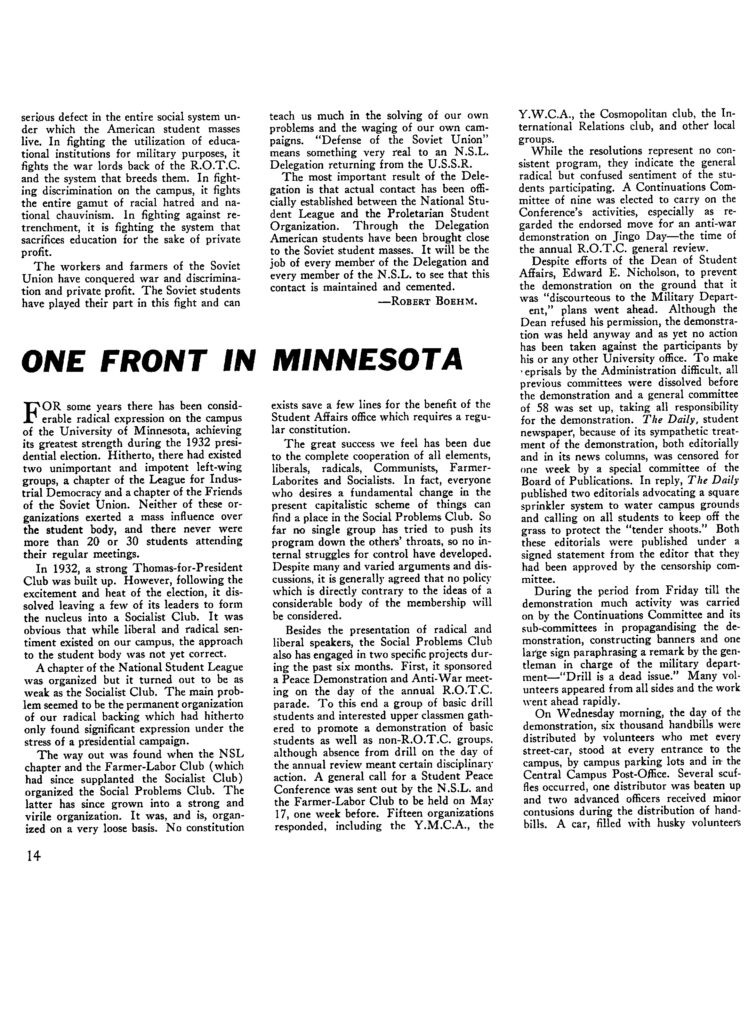

Activists took up the struggles to oppose entering a war in Europe, to stop mandatory on-campus student military drills, and to strengthen student rights. African American students led the efforts to integrate student housing and fight for the rights of African Americans on the campus. Students embraced a great diversity of politically progressive opinions at the University of Minnesota, which included visions inspired by communism, socialism, liberalism, labor rights, and the visions of the Farmer-Labor Party. Students at the University of Minnesota and elsewhere worked for civil rights on and off campus.

President Lotus Coffman, Dean of Student Affairs Edward Nicholson, and a small number of University of Minnesota Regents were personally opposed to left-wing politics and began to question why there were radicals on the campus. They treated a student movement and student political debates as problems to be contained rather than as a normal part of either American or campus life. At the same time, some politicians, legislators, and citizens attacked the University of Minnesota as a campus that harbored anti-American Communists, vastly exaggerating or inventing the number of faculty or students who identified as communists for their own political purposes.

Republican Politician and Dean of Student Affairs Create Campus Political Surveillance

Ray P. Chase (1880–1948), a Republican operative, aggressively advanced the idea that Communists had too much power at the University of Minnesota and in Minneapolis. During the mid to late 1930s he made those accusations foundational to the campaigns of Republican candidates for political office.

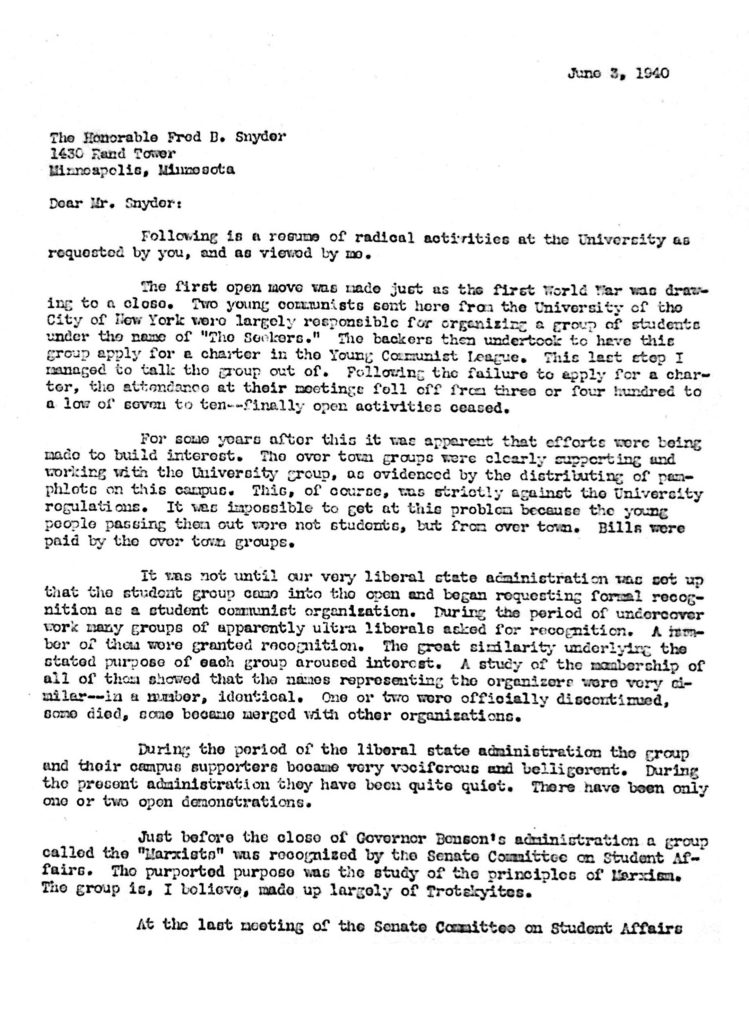

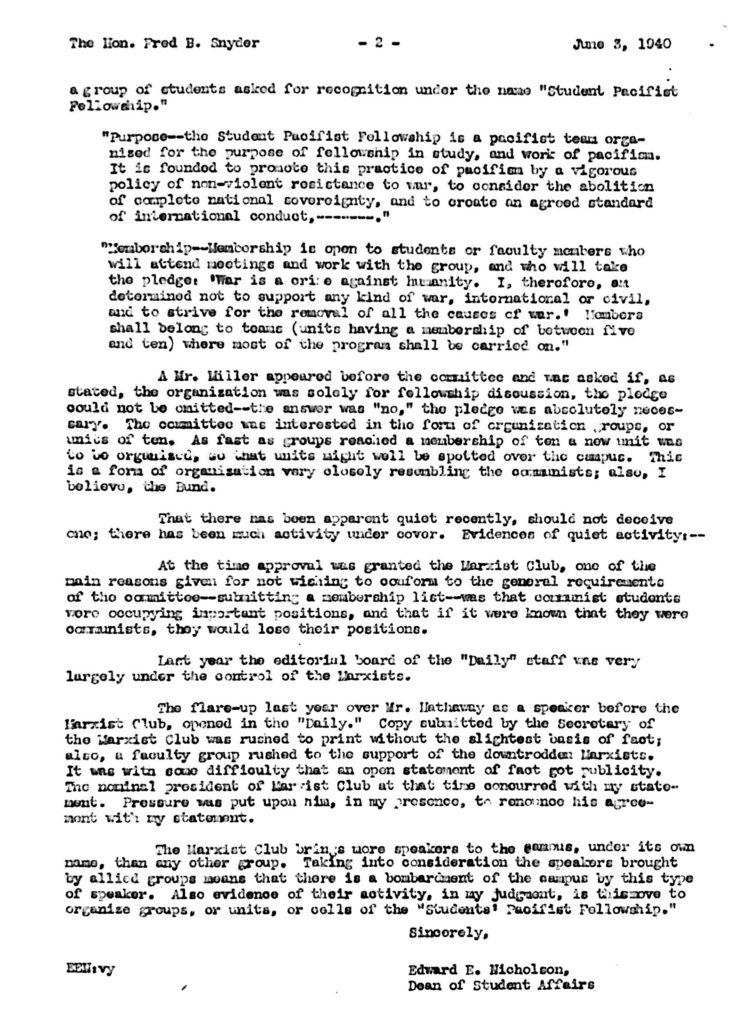

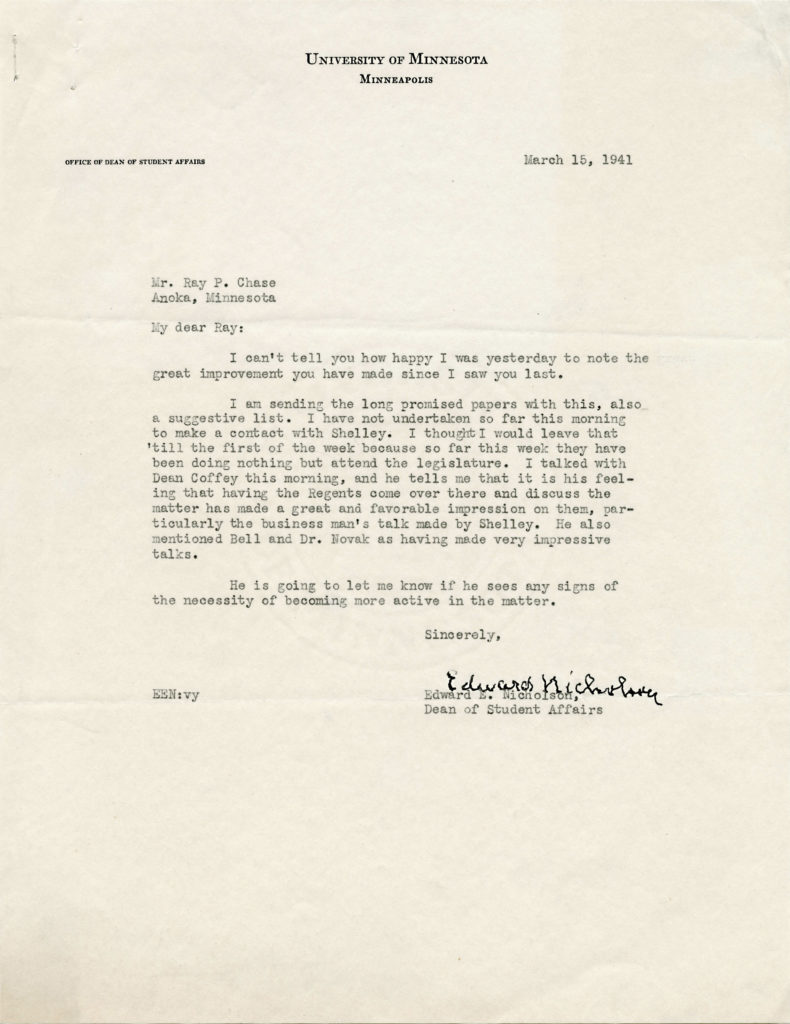

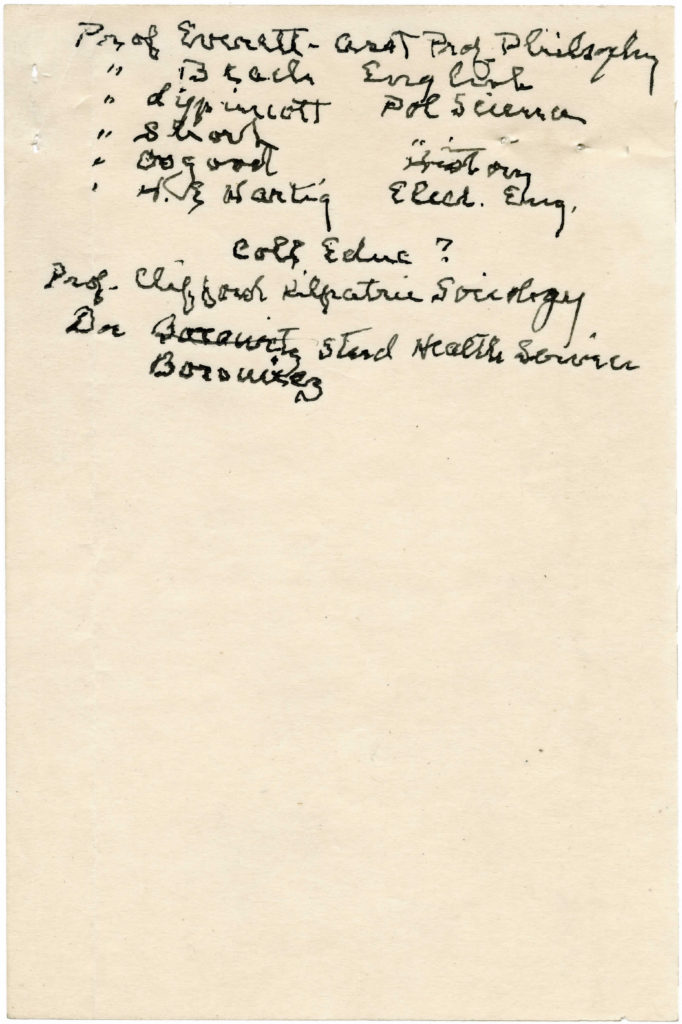

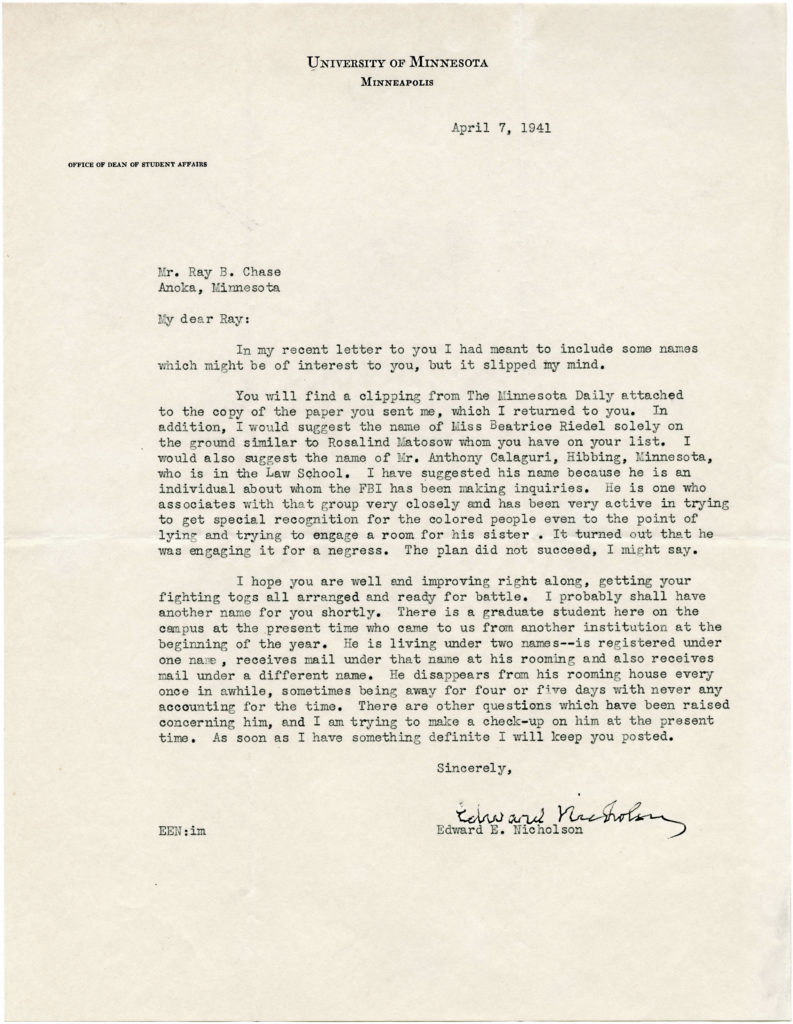

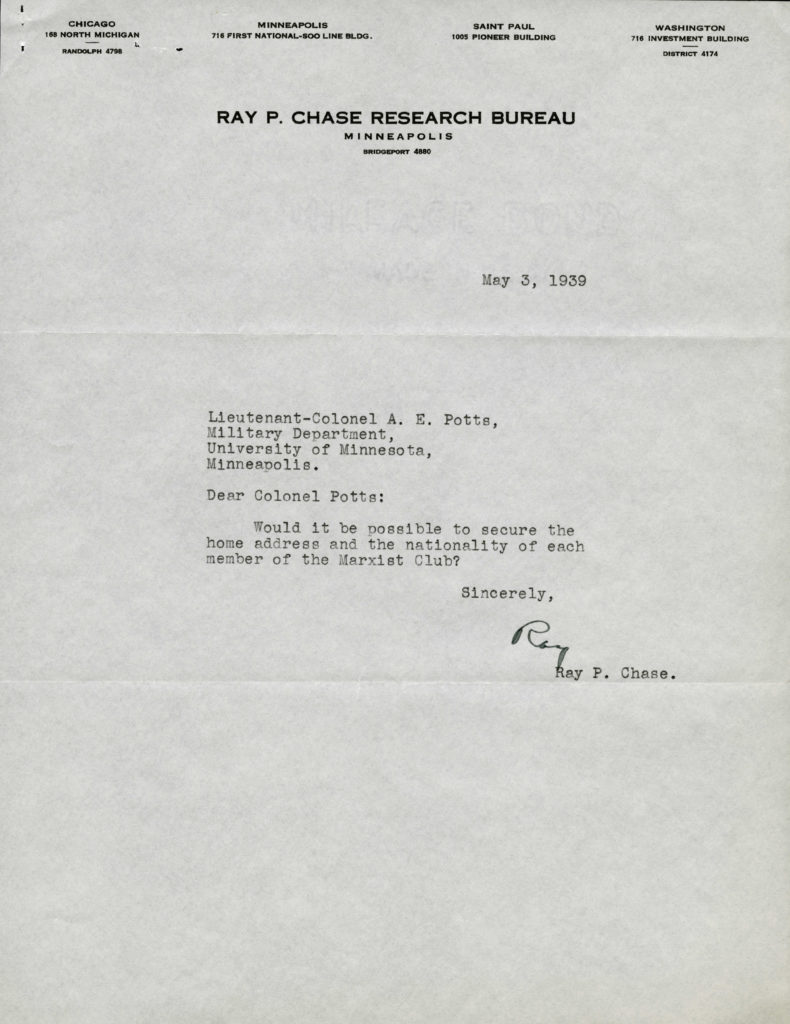

Ray Chase could not have accomplished this task without a close working relationship with Dean Edward E. Nicholson (1873–1949), who held the position of Dean of Student Affairs at the University of Minnesota from 1919 until his retirement in 1941. Dean Nicholson provided Chase not only with the names of faculty and student activists, but their on-campus activities and the political organizations they joined and led, as well as his reflections on radicalism on the campus. His lists and abstracts of University Senate meetings about student petitions for recognition of left-wing organizations remain in Chase’s papers, which are housed at the Minnesota Historical Society. Ray Chase’s requests for information about the activities of students and on-campus speakers are there as well, and can be found in the Documents section of this website. Correspondence from no other University of Minnesota official who had access to that information appear in the voluminous papers of Ray Chase, however he did receive spy reports about left-wing student groups from Lieutenant Colonel A. E. Potts, the head of the ROTC on campus

Information about left-wing student activism flowed from Nicholson to members of the Board of Regents and to other administrators beginning in the 1920s, and from Nicholson to Chase, apparently beginning in the 1930s. Nicholson shared this information in order to track “radical” students and a small number of faculty. Nicholson was also sending information about students, at least in the 1920s, to anti-labor organizations that had surveillance units, to be discussed below, and to the FBI.

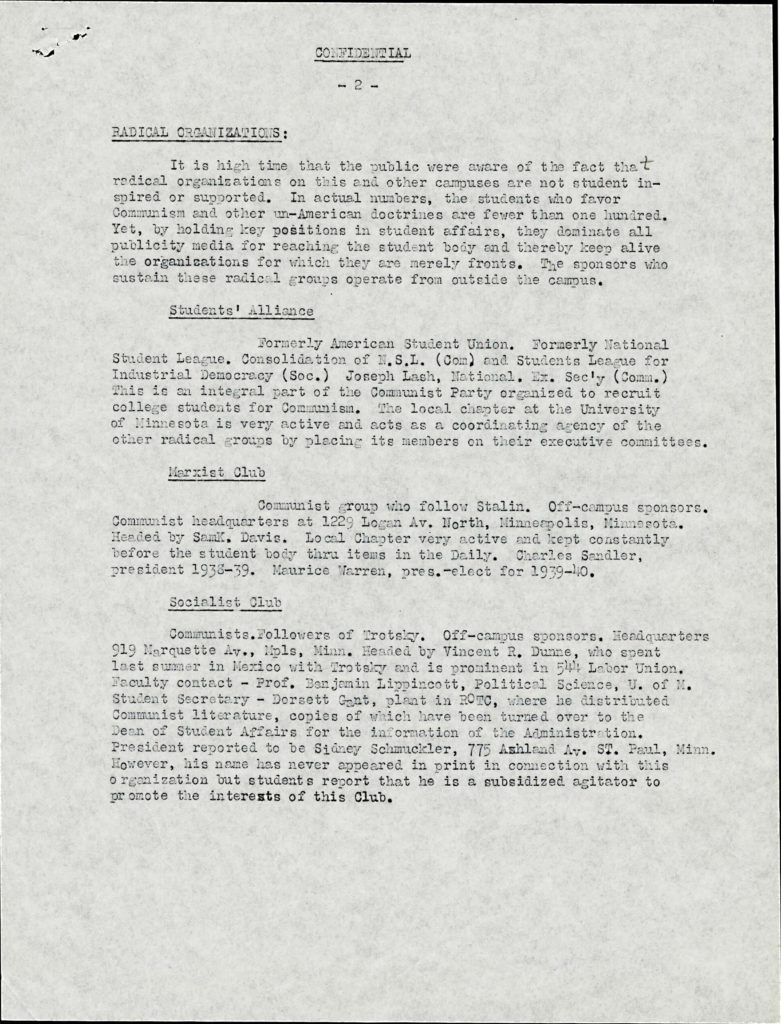

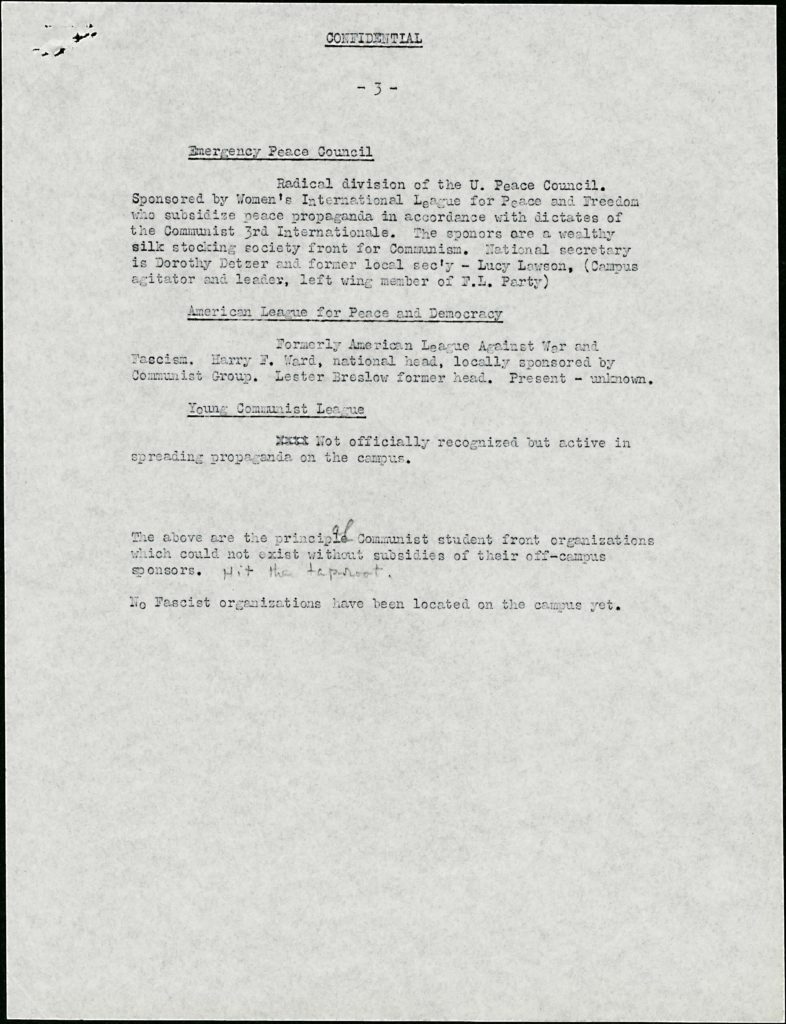

Together, Ray Chase, through his Ray P. Chase Research Institute, Dean Edward Nicholson, and others contributed to making the University of Minnesota a political surveillance campus, where the monitoring of student political activity became the norm. At their behest, left-wing political clubs were infiltrated by students or people who appeared to be students, who worked for administrators, and whose notes were ultimately sent to Chase. Students were queried about their political beliefs at meetings of the University Senate on Student Affairs Committee if they wanted to create organizations, and that information was passed on to Chase as well. On-campus political rallies were monitored, and information about them was sent to University administrators, including President Coffman, and eventually Chase.

Surveillance information became an invaluable commodity to be used by Chase to influence and affect Minnesota elections. Nicholson was an avid supporter of this work. Chase used every technique available to him to paint his opponents with a “red” (a term applied to Communists) paint brush, including innuendo, outright deception, racism, and antisemitism. Chase and Nicholson also collaborated on influencing the choice of regents, which is discussed in the essay for this website “Regent George Leonard and the Political Fight Over Selecting Regents,” and the interactive feature “How Leaders of the University of Minnesota Used and Abused Power”.

The rise of extensive surveillance in the United States grew out of political changes that began with the nation’s entry into WWI. The expansion of espionage developed in tandem with a successful movement of organized labor and the Russian Revolution and expanded during the Great Depression as industries sought to control their workforce. As early as the 1920s, and throughout the 1930s and the 1940s, university administrators used surveillance not only to monitor but to punish student activists. Charges of disloyalty were leveled at faculty and students at universities throughout the United States, including the University of Minnesota. Because the student movement was committed to ameliorating economic inequality and thus supported unionization as well as equality for Black Americans, the rights of all students to an education, and fairly paid labor, they were caught in the webs of surveillance that were woven together on and off campus by administrators and leaders of conservative and pro big business groups.

Ray Chase and Edward Nicholson’s Shared Political Agenda

Ray Chase, past State Auditor and Congressperson, and Edward Nicholson, long-time Dean of Student Affairs, seem an unlikely pair to be active together in Minnesota and University politics. Nevertheless, the ten existing letters that they exchanged between 1936 and 1941 reveal two men who avidly collaborated on political matters. Every letter from Chase asked for information from Nicholson on political matters related to the University of Minnesota. Most letters from Nicholson provided information and some asked for help in addressing political matters, particularly around influencing the choice of University of Minnesota Regents. These ten letters may be found in the Documents section of this website and are described with more context below and in the essay entitled “Regent George Leonard and the Political Fight Over Selecting Regents.”

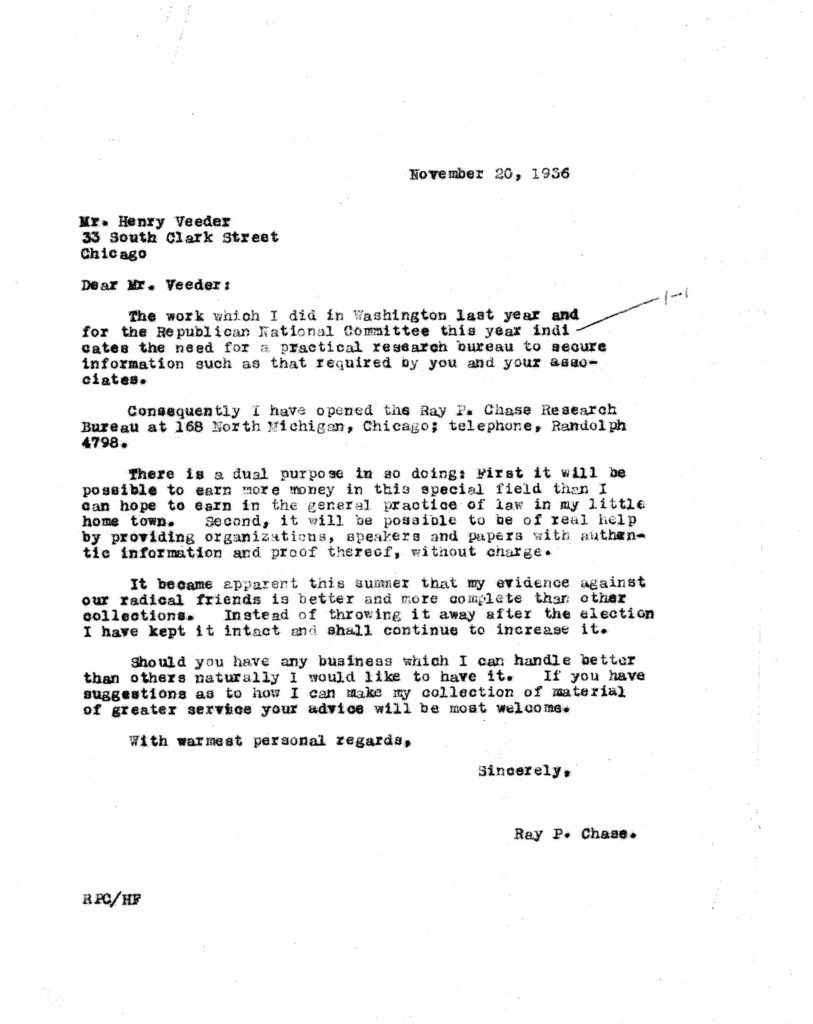

The first letter in the Chase files to Nicholson, written shortly after Franklin D. Roosevelt’s unprecedented victory over his Republican rival Alf Landon, reveals that Ray Chase was opening a business to provide information (what he loosely called “facts”) to clients, an activity he had undertaken during the 1936 election on behalf of Republican candidates in Washington D.C. and elsewhere. He intended for his business of providing information to shape political campaigns. He also promised to inform the University of Minnesota about the large number of “dangerous” students, faculty, workers, and administrators.

That first letter suggests that Chase and Nicholson had worked together for some time. Chase wrapped his announcement of his new business not only in pleasantries, but he acknowledged that Dean Nicholson did favors for him that he was anxious to reciprocate. He also requested that any information or “facts” be sent to him at his Chicago office. The letter assumed that Edward Nicholson knew just what sort of “facts” and “information” Chase sought.

What these letters unquestionably reveal is a connection between two men who not only shared a particular political agenda that Ray Chase termed “Conservative”–which more accurately would be called reactionary–but also a quid pro quo relationship in which information was exchanged for political influence and favors. Chase’s request for facts included, over time, recordings of speeches by “radical” students, information about faculty and students with left-wing political perspectives, and lists of speakers and fees paid to them. He also suggested speakers that he wanted invited to campus. This information was valuable because in the 1930s in Minnesota information about labor and political activism was central to the work of big business. Both Ray Chase and especially Edward Nicholson were part of that world. Other people on the campus of the University of Minnesota provided information to Chase that he requested, but none had a documented relationship of exchange of information for influence that he shared with Nicholson.

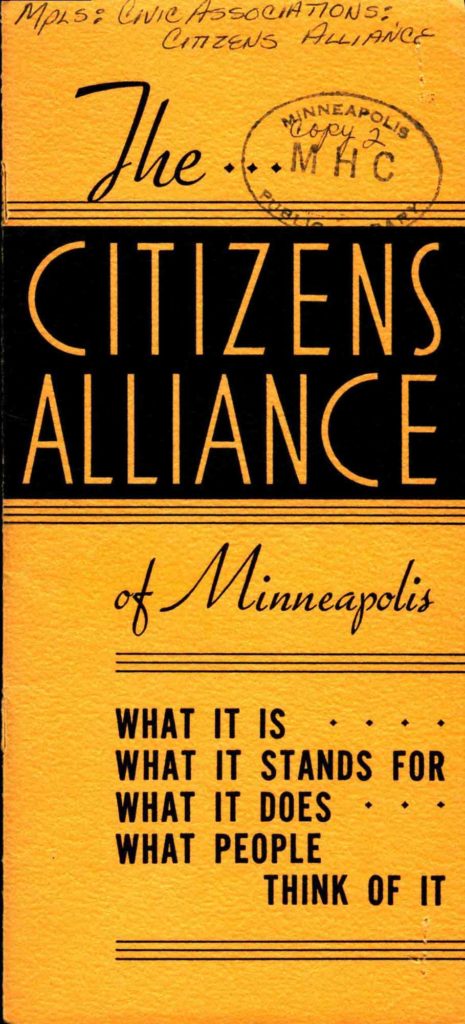

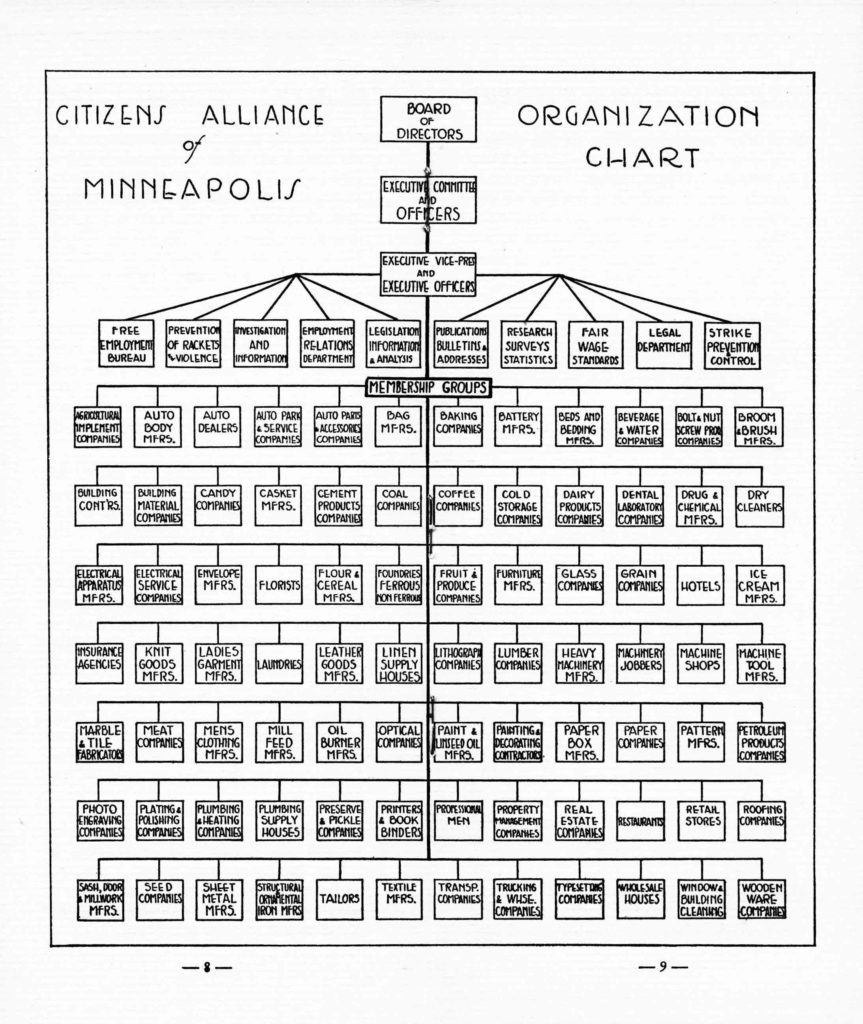

In the first decade of the 20th century, tight-knit organizations of employers in Minneapolis and St. Paul were a critical feature of political, economic, and business life. They offered the most powerful opposition to workers’ movements trying to form unions. These employer organizations were created by the leaders of the most powerful industries in the Twin Cities, including grain, milling, banking, furniture manufacturing, iron works, printing, and small businesses as well. Around WWI, as labor protested working conditions, the employers’ groups created the Citizen’s Alliance (CA) of Minneapolis that aggressively blocked labor activism. The Citizens Alliance encouraged all businesses large and small to join, but the organization was controlled by a small board made up of the leaders of the largest industries. Alongside it, the same powerful leaders of industry created the Minneapolis Civic and Commercial Association (CCA) that took on the work of defeating unions using surveillance and the employment of paramilitary units that crushed efforts to protest. Avowedly anti-Communist, the Citizens Alliance painted all of their enemies as Communists. Some in the labor movement were Communists, but the vast majority were not. The Citizens Alliance was followed by another organization with the same cast of characters called Allied Industries. William Millikan documents their activities and the central place of surveillance in every branch and iteration of these organizations. As Millikan demonstrates in his award-winning research, efforts to curtail the power of unions involved the courts, the legislature, the National Guard, an independent surveillance system, banking, and “educational” efforts to encourage “law and order.”William Millikan, The Minneapolis Citizens Alliance and Its Fight Against Organized Labor, 1903-1947 (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2001); Lois Quom and Peter J. Rachleff, “Keeping Minneapolis an Open Shop Town: The Citizens Alliance in the 1930s,” Minnesota History 50, no. 3 (Fall 1986): 105-117.

The Citizens Alliance leadership created a system of interlocking organizations that included, for example, an employment bureau during the Depression that required those applying for jobs to agree not to join unions. They built vocational schools that taught students the superiority of employers and the importance of loyalty to them. They built a direct relationship with the National Guard and had ties to the grand jury system. They had their own system of spying on unions and those they deemed Communists. The Citizens Alliance had strong allies in police enforcement, the courts, and among Republican politicians. They worked with the largest banks, which denied loans to businesses that were willing to employ unionized workers. Every business that joined the Citizens Alliance was required to take a pledge to refuse to employ unionized workers.William Millikan, The Minneapolis Citizens Alliance and Its Fight Against Organized Labor, 1903-1947 (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2001); Lois Quom and Peter J. Rachleff, “Keeping Minneapolis an Open Shop Town: The Citizens Alliance in the 1930s,” Minnesota History 50, no.3 (Fall 1986): 105-117.

The Citizens Alliance formed a Law and Order League following an intense period of labor activism in Minneapolis in 1934, which was focused on a Teamster strike. Edward Nicholson was one of four directors of the Law and Order League. He joined the leadership around 1935 and served with a General Mills Executive, among others. In addition to its opposition to unions, the League fostered a reverence for “law and order,” ideas contested by the student activists who frequently challenged the Dean of Student Affairs at the University of Minnesota.William Millikan, A Union Against Unions: The Minneapolis Citizens Alliance and Its Fight Against Organized Labor, 1903-1947 (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2001), 325-326.

During this period, Ray Chase no longer held political office and was working with Republicans and big business to defeat not only Farmer-Labor Party candidates, but the commitments of the New Deal, and the rights of farmers and workers. Chase gathered and provided information to General Mills and other clients. This was one arena of Nicholson and Chase’s political activism.

Edward Nicholson and Ray Chase shared political agendas created by the Citizens Alliance and the interests that they represented. Those interests depended upon an extensive system of informers, spies, and infiltrators developed by the Citizens Alliance and its many branches and organizations. The Citizens Alliance created The Special Services under the leadership of Lloyd M. MacAloon in 1929. He focused his surveillance on “radicals and trade unionists” and the Communist Party. The organization employed “investigators” who infiltrated every labor union organization in the city, even joining the ranks of union leadership. These spies provided information about union membership, finances, and plans to organize shops, all invaluable to the anti-union forces of the Citizens Alliance. MacAloon also kept copious files on “progressive thinkers,” college professors, lawyers, and anyone who might be viewed as “liberal” or might question business. His files gave basic information about individuals, linked them to others with these attitudes, and documented their personal histories. The Law and Order League that Nicholson helped to lead devoted two-thirds of its budget to intelligence gathering. This surveillance work was focused on the Farmer-Labor Party, “socially minded and progressive movements,” and others termed “enemies of society.”William Millikan, A Union Against Unions: The Minneapolis Citizens Alliance and Its Fight Against Organized Labor, 1903-1947 (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2001), 223-224.

Chase and Nicholson’s quid-pro-quo relationship was fully aligned with the work of the Citizens Alliance. They viewed those students and faculty members as most dangerous to the University of Minnesota who were activists who aligned with the Farmer-Labor Party, were pro-union, or were critical of capitalism and opposed war–in short, the entire national student movement of the 1930s. Dean Nicholson and Ray Chase made common cause in their rejection of these ideas and activism, and they pursued the politics of law and order that deemed various groups “enemies of society”–from certain students and faculty to Farmer-Labor appointees to the Board of Regents.

Ray P. Chase and His Campaign Against the University of Minnesota

Ray Chase was born in Anoka, Minnesota and graduated from the University of Minnesota in 1903. He received a law degree from William Mitchell Law School in 1919. He served as a municipal judge of Anoka, Minnesota from 1911 to 1916 and as deputy State auditor and land commissioner of Minnesota from 1916 through 1920. Chase was State Auditor from 1920 to 1931 and a member of the United States House of Representatives from 1933 to 1935. He failed in his bid for reelection to the House of Representatives as well as to become Governor of the State of Minnesota, losing to Farmer-Laborite Floyd B. Olson in 1930. He was a popular and highly praised figure among conservatives and extremists with strong ties to a number of right-wing organizations that were popular in Minnesota in the 1930s. He was opposed to taxation and remained a right-wing figure in Republican politics.Hyman Berman, “Political, Antisemitism in Minnesota During the Great Depression,” Jewish Social Studies 38, no. 3/4, (Summer/Autumn 1976): 257. Chase is also discussed in Dorothy Dorsey Hatle, The Ku Klux Klan in Minnesota (Charleston, South Carolina: History Press, 2013), 65-67, 70-71, 152-153.

The Supreme Court of Minnesota, in “State Ex Rel. University of Minnesota and Others v. Ray P. Chase,” found for the University of Minnesota in its 1928 ruling. The decision stated that the rights of the Regents could not be transferred to “any other board, commission, or office.” This decision gave the University of Minnesota and its Board of Regents a special legal status of “constitutional autonomy,” which made it a separate entity rather than an agency of government. Nevertheless, Ray Chase continued to intervene in the affairs of the University throughout the 1930s and early 1940s, although his focus was on political activism on the campus and a relentless hunt to reveal those he labeled Communists.State ex Rel. University of Minnesota v. Chase, 175 Minn. 259, 220 N.W. 951 (Supreme Court of Minnesota, Jul7 27, 1928), casetext, https://casetext.com/case/state-ex-rel-university-of-minnesota-v-chase.

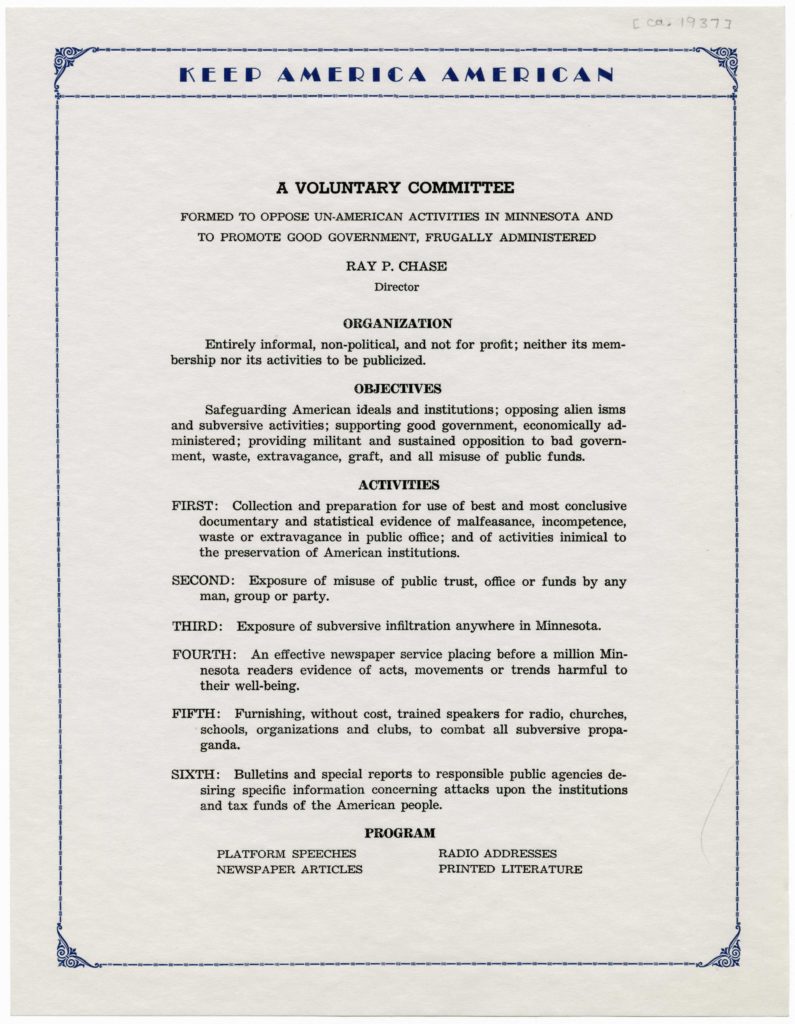

Chase opened the Ray P. Chase Research Institute in Minneapolis, Washington D.C., and Chicago in 1936 following FDR’s reelection, which he had worked against. His institute, which would focus on Minnesota, was devoted to the same type of work he did in his effort to defeat FDR, seeking information, often distorted or untrue, to exert political influence over every aspect of political life. His goal was to collect and keep “valuable information” on those whose ideas he opposed. He found spies, colleagues, and those who shared his political vision to gather information for him. However, he was not bound by facts and frequently invented his opponents’ positions in order to advance his political agenda. Chase gathered information to use in order to smear the Farmer-Labor politicians running against the Republicans he supported.

He devoted himself to a number of overarching themes, including “Keep America American,” and saw enemies of that vision in the Farmer-Labor Party, Jews, and left-wing activists, among others. He and his allies decided who was “Un-American,” “Red,” “Trotskyite,” or “ Communist.” He vowed to eliminate communist activity in higher education, particularly at the University of Minnesota. Chase’s claim to have “documentary evidence” underlines why he needed allies at the University of Minnesota to provide him information that he could twist to make a case for his extreme anti-communism position. He promised more sympathy from the legislature if the University of Minnesota would work with him in attacking “academic freedom,” or the open exchange of ideas.The phrase “Keep America American” was derived from the motto of the American Coalition of Patriotic Societies, founded in 1929 by one of the architects of the movement to limit immigration to the United States, John B. Trevor Sr. Chase’s choice of phrase aligned him with xenophobic, anti-immigrant activists and eugenicists. Yoni Applebaum explores the history of this phrase in “The Trouble with Keeping America ‘American,’” The Atlantic, December 15, 2011, https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2011/12/the-trouble-with-keeping-america-american/249960/. See also Erika Lee, America for Americans: A History of Xenophobia in the United States (New York: Basic Books, 2019), 140.

For Chase, taxation and public-sector jobs, even in the midst of the Depression, “paved the way for communism.” What Chase termed government and University “inefficiency” often meant the use of funds for the common good.

Upon appointment to the role of Dean of Student Affairs, Nicholson exercised unprecedented control over the lives of students because he oversaw student discipline; housing; student activities; the distribution of all information and publications to students; the Student Forum that invited off-campus speakers for lectures and convocations; the publication board that advised the Minnesota Daily, the literary journal, and humor magazine; and the control of many political activities. He created the apparatus in the University Senate Student Affairs Committee that made it possible to monitor and contain the ideas of students whose politics disagreed with what he believed was American. Student members of the committee were appointed by President Coffman. Nicholson appeared to select faculty members. He also refused recognition of some student organizations, including the National Student League, the Student League for Industrial Democracy, the Young Communist League, and the American Student Union (although he eventually approved the ASU). Students who were directly or tangentially associated with these student groups and allied causes (labor rights, racial integration, diversity of thought, racial and religious freedom and rights) became targets for administrative surveillance, as did every other political group he approved.Historian James Gray’s history of the University of Minnesota from 1851 to 1951 discusses Dean Nicholson’s tenure at the University. He praises his “unselfish interest in the welfare of students” and notes the many stresses faced by students due to “war, depression, and changing mores.” He refers tactfully to his “inflexibility,” which he attributes to Nicholson’s “idealism.” He also suggests that there was an irony in his nickname “Dean Nick,” since it evoked his opposite, Saint Nick. Gray lacks any acknowledgment of Nicholson’s right-wing politics. At the same time, he makes clear that Nicholson was viewed as rigid, which is supported by other sources. James Gray, The University of Minnesota 1851–1951 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1951), 349-356.

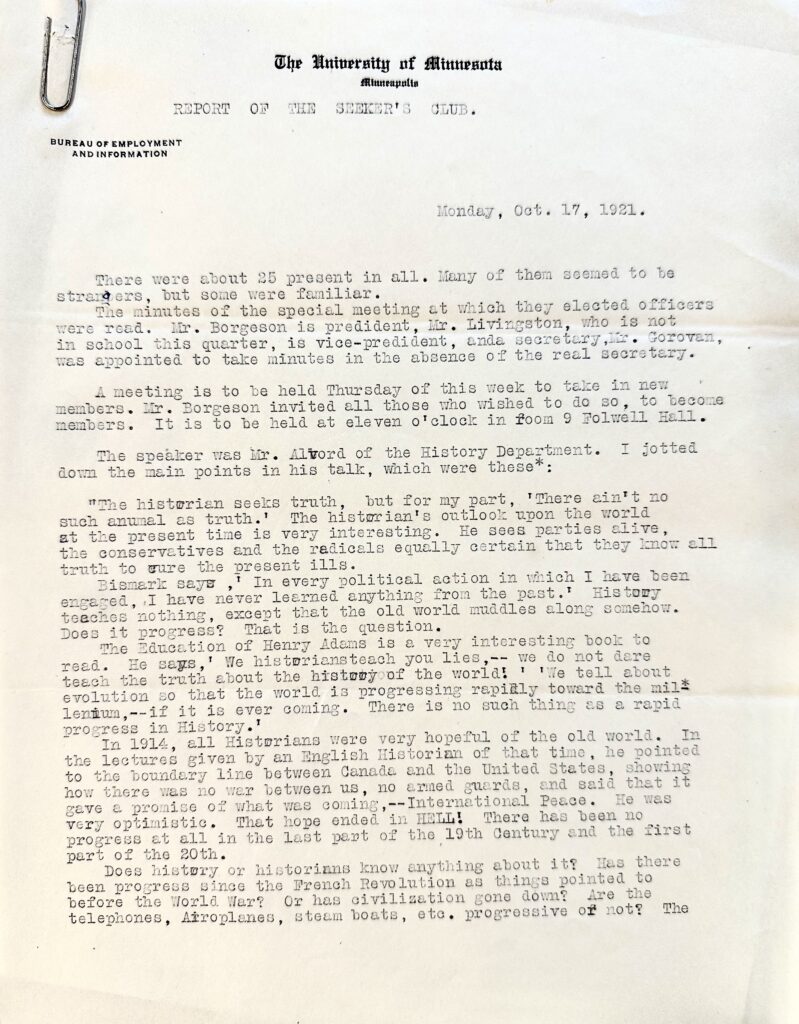

Edward Nicholson’s First Known Surveillance Project: The Seekers 1920-1921

Dean Nicholson identified the beginning of radicalism at the University of Minnesota with the arrival on campus of two students from New York, who he identified in parentheses as “Jews” in a report drafted for his own files but which he also shared with regents and a partisan political operative. These two students and others petitioned Nicholson’s office to begin a group in 1920 called the Seekers, which the dean approved. The Seekers’ weekly meetings attracted 70-80 students in the fall and well over 100 by 1921, and then their numbers dwindled by the end of that academic year.Dean of Student Affairs Edward Nicholson’s Report “Radical Organizations,” undated, page 1, Dean of Student Affairs, Box 10, 1935 Radical Organizations and Activities, University of Minnesota Archives.

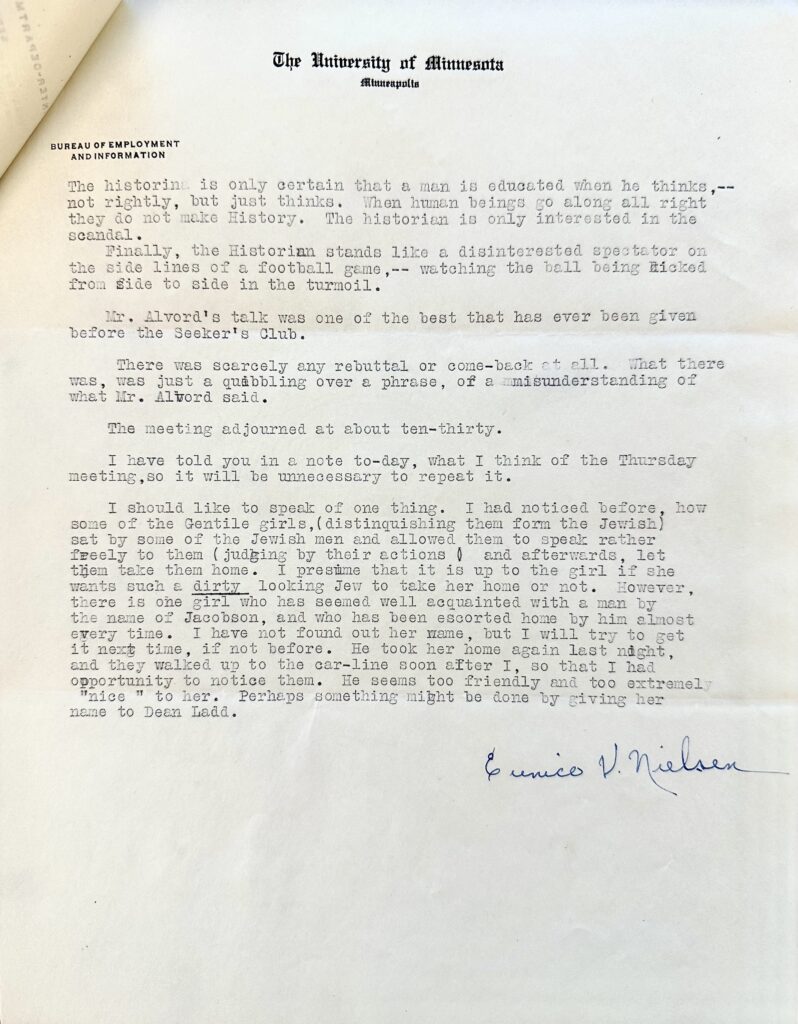

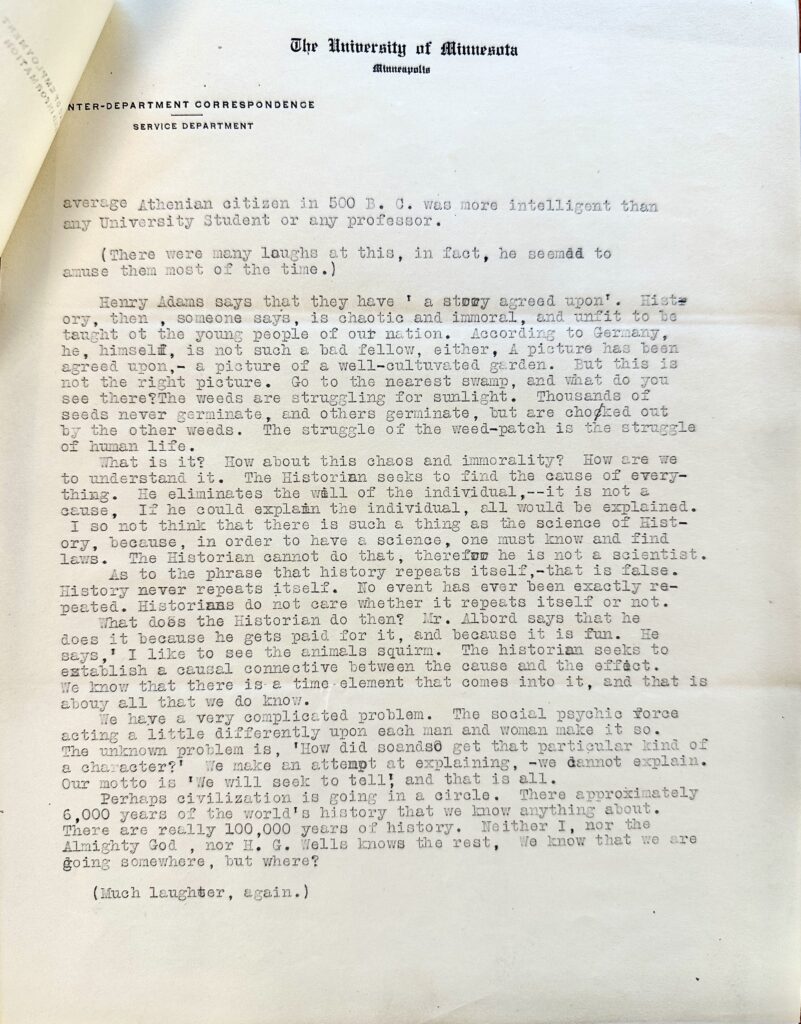

Nicholson’s file on the organization consists of weekly reports sent to him by people who worked within the Student Affairs office who he assigned to spy on the group. Most reports were written by E.V. (Eunice V.) Nielsen, an employee of the Service Department, which was part of Dean Nicholson’s office. Each of her reports, written on University of Minnesota stationery, listed every name of those who attended that she could learn, speakers’ names, and the details of lectures and conversations. The file also includes Nicholson’s reports to President Coffman and correspondence with Fred B. Snyder, chair of the Board of Regents from 1914-1950 and a politically conservative Republican politician and anti-labor activist.All of the spy reports are located in the folder “Seekers Club,” Dean of Student Affairs, Box 12, University of Minnesota Archives. Snyder was a founder of the Minneapolis Civic and Commerce Association and was closely aligned with the Citizens Alliance, the organization founded by the city’s most powerful industries to stop workers from unionization. Snyder also headed the Minneapolis loyalty campaign during WWI, which was a full-throated attack on any citizen viewed as disloyal to the cause of WWI, a national campaign that was ultimately repudiated for its excesses by Congress and President Harding. William Millikan, A Union Against Unions: The Minneapolis Citizens Alliance and Its Fight Against Organized Labor, 1903-1947 (Saint Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2001), 22, 119.

In the early months, Nicholson’s spy referred to the Seekers as the Intercollegiate Socialist Society, also founded in 1920. The national organization subsequently called itself the League for Industrial Democracy (LID). The Seekers was identical in intent and conduct with the LID, and thus most likely was affiliated with the group in some way or was inspired by it. Its purpose was to educate students about the political and economic issues of the day. Neither the LID nor the Seekers advocated activism.Robert Cohen, When the Old Left Was Young: Student Radicals and America’s First Mass Student Movement, 1929-1941 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 32-35.

Nicholson’s own reports emphasized that the group adhered to his rules and brought no speaker without his permission. Each meeting, held in Folwell Hall 9, featured speakers, often faculty members. Nevertheless, Nicholson viewed them as a threat and sent spies to the group, as he did to every left-wing campus group throughout the 1930s until his retirement. Nicholson paid lip service to tolerance for student involvement in left-wing organizations. In fact, he monitored them through spies who gathered names and reported to him, and he shared that information beyond the campus.

Miss Nielsen’s reports sent directly to Dean Nicholson reeked of antisemitism as she commented incessantly on the presence of people she presumed to be Jews in the group. Not only did she count them and name them, but she also commented on their lack of cleanliness and appearances. In one report she caricatured the accent of Bessie Kasherman for paragraphs, explaining that “tone and inflection of the voice plays an extremely important part in giving the meaning of what one is saying.” She never explained what that meaning was. The following October, Nielsen grew increasingly anxious at the interactions between what she described as “Gentile girls,” (not Jewish, she explained) who sat by “Jewish men and allowed them to speak rather freely to them.” She noted that some of those girls let “them” take them home. Miss Nielsen opined that it is up to the girl “if she wants such a dirty (her emphasis) looking Jew to take her home.” Another girl she observed was waiting at the same time as she was at the “car-line.” A man named “Jacobson” (an obviously Jewish name) “seems too friendly and too extremely ‘nice’ to her.” Nicholson’s spy recommended giving the girl’s name to Dean Ladd (Tessie S. Ladd, acting Dean of Women).Eunice V. Nielsen to Dean of Student Affairs Edward Nicholson, Reports on the Seekers Club, May 9 and October 17, 1921, Box 14, 1920-1921 Seekers Club, University of Minnesota Archives, Minneapolis, MN.

Nielsen subsequently explained to Nicholson and his assistant Mr. Poucher that she could not attend the next meeting where people would sign up to be members. Her mother considered it “too big a risk…since there are such a large number of Jews that are members.” Nielsen suggested “academic students or faculty should take over spying.” One of the last spy reports on the Seekers was filed the next month by a man. He concluded: “Attendance: Thirty. Majority Jewish, foreign accents. One colored man.”Eunice V. Nielsen to Dean of Student Affairs Edward Nicholson, Report on the Seekers Club, October 18, 1921, Box 14, 1920-1921 Seekers Club, University of Minnesota Archives, Minneapolis, MN; James P. Patterson to J.C. Poucher, Report on the Seekers Club, November 8, 1921, Box 14, 1920-1921 Seekers Club, University of Minnesota Archives, Minneapolis, MN.

Dean Nicholson valued these weekly reports that obsessively detailed the presence of Jewish students and that, like him, conflated Jewish, Russian Jew, and communist (despite a range of political perspectives in the group). The obvious antisemitism of these reports extended to comments on the dating habits and personal appearances of students. For more than a year, Nicholson made no objection to the linkages drawn between race and politics by those he sent to spy on the group.

How Edward Nicholson Used the Seekers Spy Reports

Nicholson communicated information about the Seekers Club to people in power. He appeared to be in regular communication about the Seekers Club with Fred B. Snyder, chair of the Board of Regents. Snyder was a Republican politician who served in many political offices and was a founder of the Civic and Commerce Association and active in its many related organizations. In turn, Snyder shared information with Pierce Butler, also a regent, who was soon to become an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. Snyder praised Nicholson for putting the group “under constant surveillance.” Snyder named two students as the “worst,” noting that one is “a Russian Jew with anarchistic tendencies.” Nicholson also sent a report on the Seekers to President Coffman.Three years prior to this exchange of letters, Regent Pierce Butler demanded that University of Minnesota President Marion L. Burton immediately assemble the Board of Regents in order to question Professor William Schaper, a distinguished political scientist and faculty member of seventeen years. Lacking any formal charges or an opportunity to respond to accusations, Schaper was fired for his “attitude” and Butler’s apparent anger that Schaper supported “public ownership of street railways.” See “Education: Monument to Freedom,” Time Magazine February 7, 1938, https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,789437,00.html. Fred Snyder to Pierce Butler, December 22, 1920, Dean of Student Affairs, Box 14, Seekers Club, University of Minnesota Archives.

In these reports, in addition to listing speakers, Nicholson explained that he was “able to place” people who attended meetings of the University of Minnesota Seekers Club at meetings of groups without University ties, including the Industrial Workers of the World, the Non-Partisan League, and groups he referred to as “socialist party” and “communist party,” again identifying “Jews” as communists. Nicholson was able to do this thanks to his ties to organizations involved in spying on the Left throughout the Twin Cities.Edward Nicholson to Lotus Coffman, July 7, 1921, Dean of Student Affairs, Box 14, Seekers Club, University of Minnesota Archives; William Millikan, “Maintaining Law and Order: The Minneapolis Citizen’s Alliance in the 1920s,” Minnesota History 51, no.6 (Summer 1989): 228-229; William Millikan, A Union Against Unions: The Minneapolis Citizens Alliance and Its Fight Against Organized Labor, 1903-1947 (Saint Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 2001), 213-243.

Fred Snyder’s letter to Pierce Butler underlined Nicholson’s tactics. He wrote, “certain members have been reported for investigation to the organization in this city constantly at work on ferreting out people who do not believe in our government.” His reference is to the extensive intelligence operations which grew under the Citizens Alliance and the Civic and Commerce Association. At the end of WWI, these organizations created a new surveillance unit to replace the one in use during the war. Nicholson explained to Coffman that he “placed” student members of the Seekers Club at every organization under the surveillance apparatus of the Citizen’s Alliance and other related organizations.

Dean Nicholson was deeply embedded in surveillance well beyond the University of Minnesota. Nicholson sent his employees to spy on these meetings in order to gather student names which he planned to send to those who maintained lists of people viewed as politically problematic by various Twin Cities organizations. Nicholson’s handwritten note to Coffman on his report cautioned him that “The information relative to outsiders should not be given any publicity as it would probably enable interested parties to locate my sources of information,” referring to the network of spies who infiltrated the left-wing organizations Snyder described to Butler.Fred Snyder to Pierce Butler, December 22, 1920, Dean of Student Affairs, Box 14, Seekers Club, University of Minnesota Archives; Edward Nicholson to Lotus Coffman, Dean of Student Affairs, Box 14, Seekers Club, University of Minnesota Archives.

Ray Chase and Edward Nicholson Created a Political Surveillance Campus

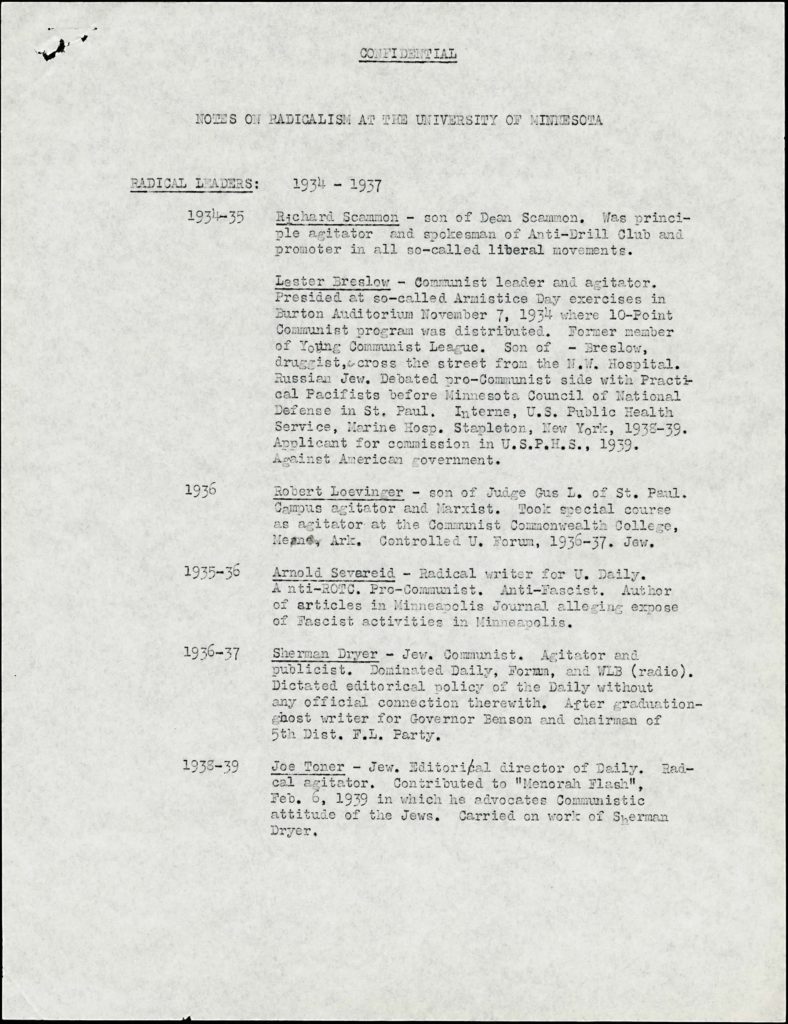

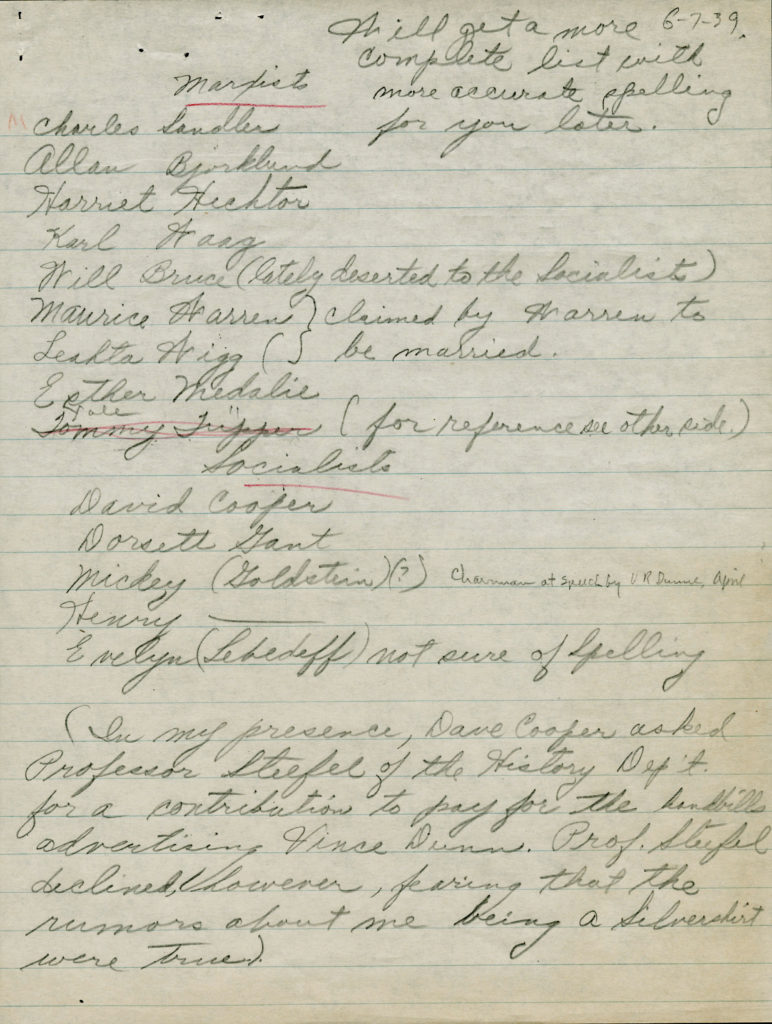

Dean Edward Nicholson, among others, provided the names of people he viewed as radicals or Communists to Ray Chase. The Chase archive at the Minnesota Historical Society contains lists of students who were key leaders in the anti-war movement as pacifists or anti-militarists, worked on the Minnesota Daily, or were active in student government. Abstracts of University Senate meetings, found in Chase’s files, contained the names of students who sought approval for University recognition of a variety of political organizations, a process that Nicholson controlled. White students involved in the fight to end segregated housing were included as “Troublemakers.”African American students were not included in any of the existing lists because they were not viewed as radicals or Communists by Chase or Nicholson. Others on campus also provided names.

What was particularly striking about this list was the absence of names of some students who described themselves as Communists. Rather, this list is devoted overwhelmingly to members of the Jacobin fraternity, which is discussed in the essay for this website “Student Movements on Campus and the Struggle for Students’ Rights.” Dean Edward Nicholson was particularly embattled with these young men, who occupied important roles in the leadership of the Minnesota Daily and the anti-war movement. The lists include those students who Dean Nicholson disliked because of their activism and attacks on his authority.

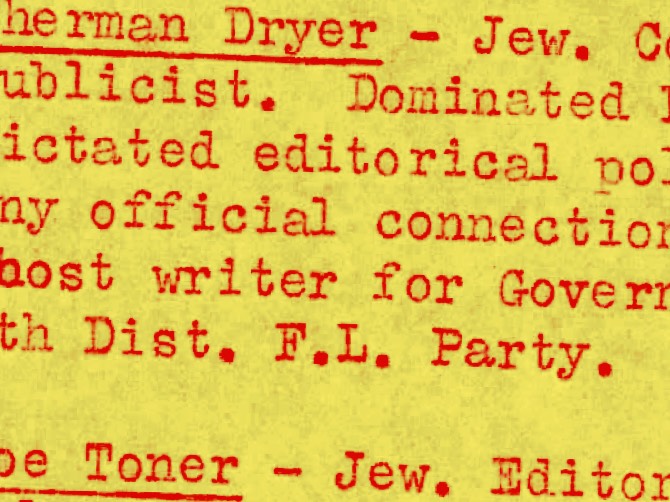

Ray Chase then created dossiers on these students that sometimes included their parents’ names and occupations and noted if they were Jews. He labeled some of these activists as “Communists,” when virtually none of them described themselves with that term. Chase saw left-wing Jews as dangerous agitators. Non-Jews on the lists were never identified by race or religion.

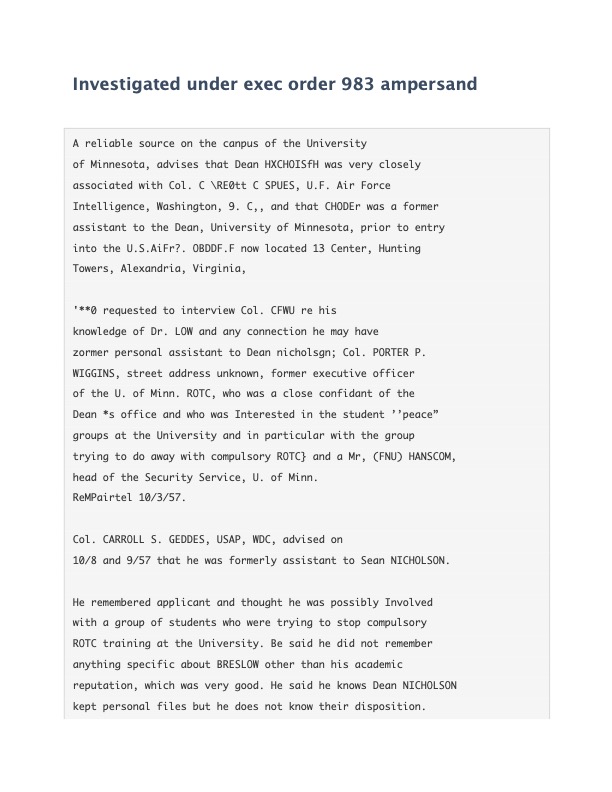

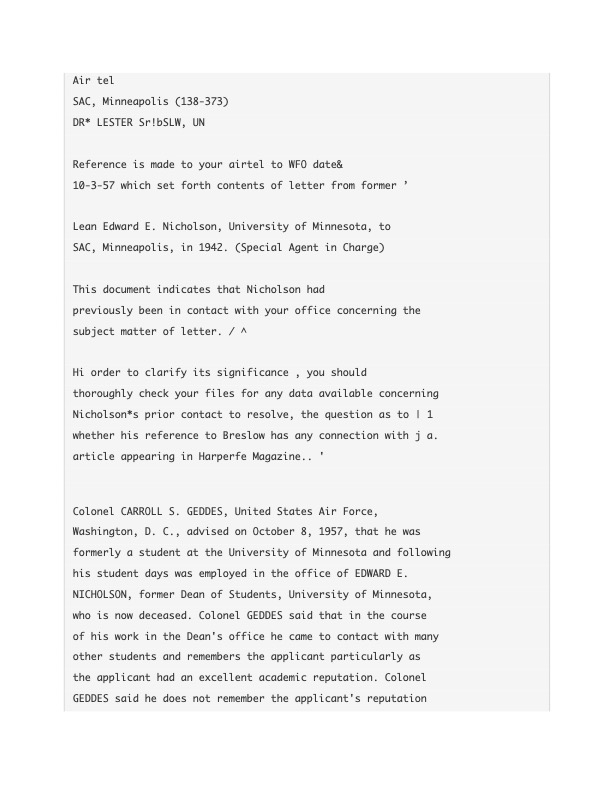

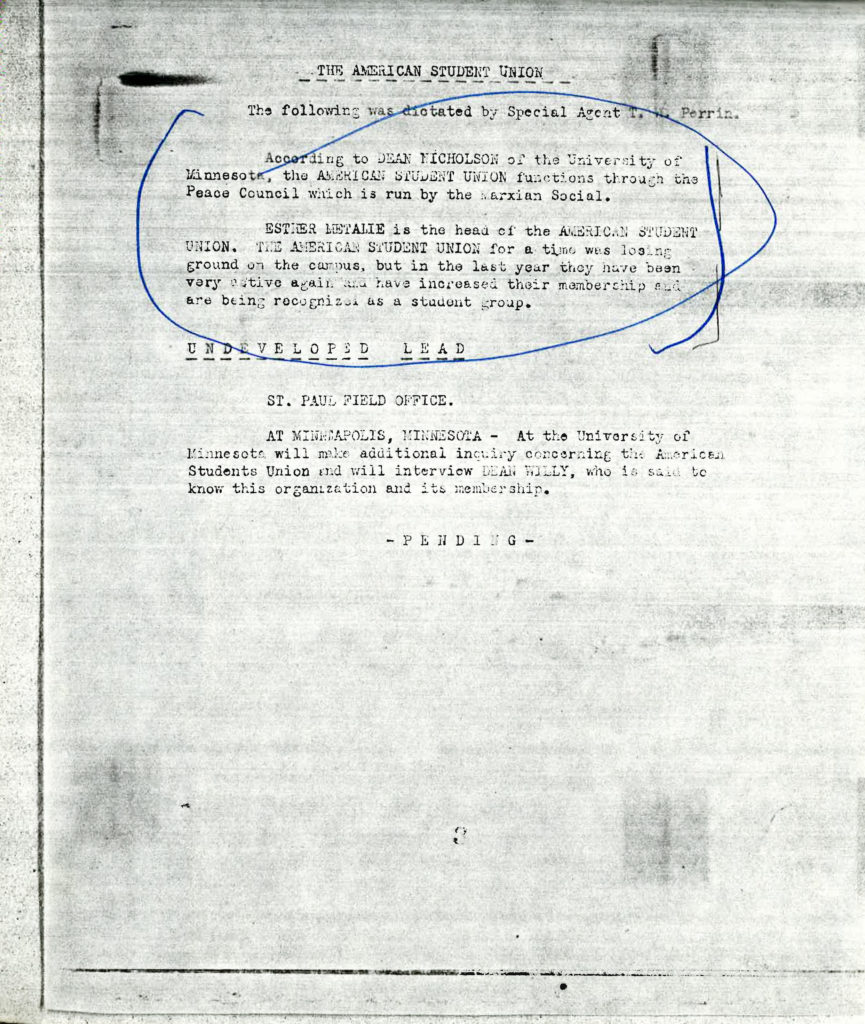

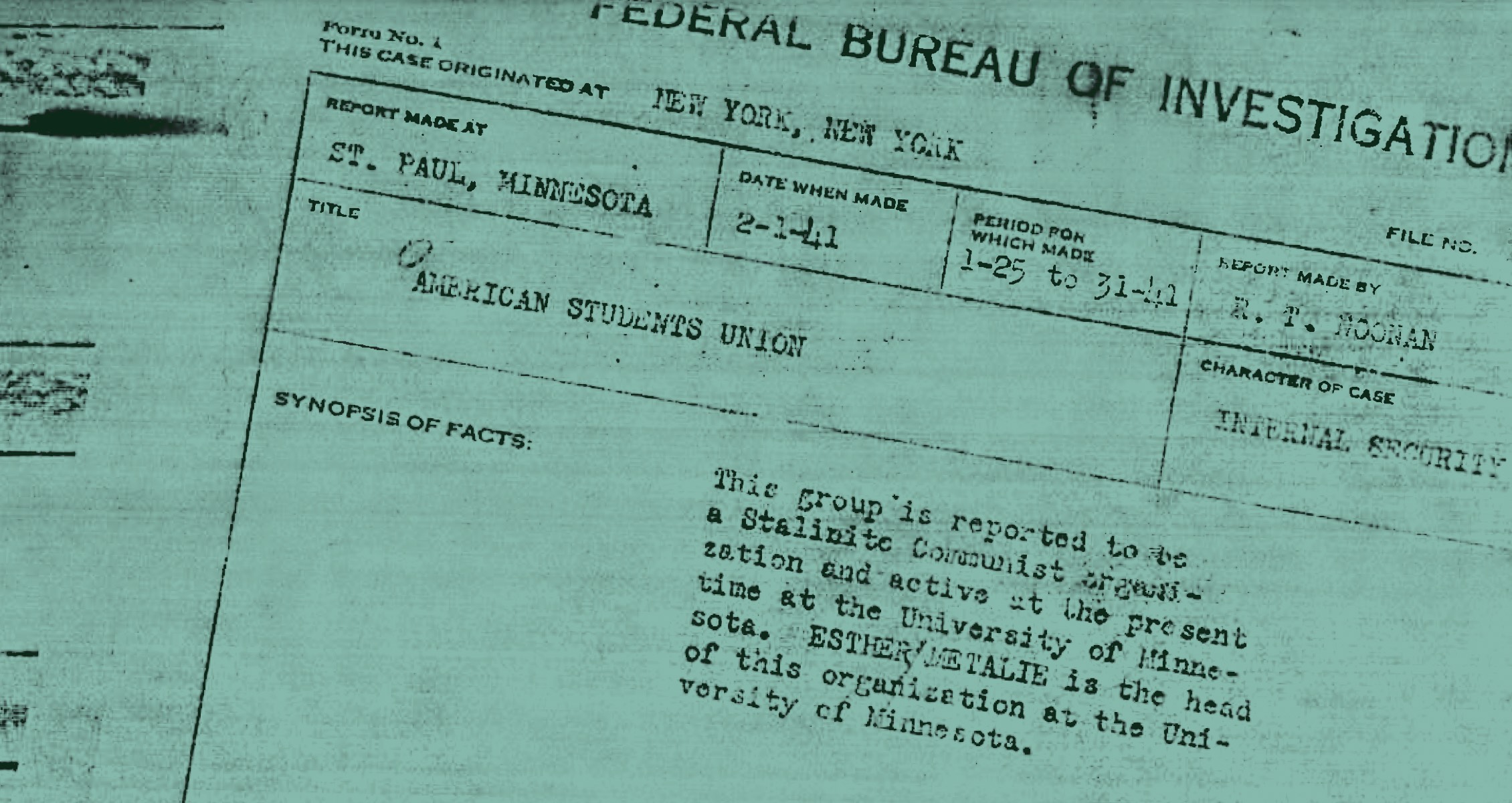

In 1941, Dean Nicholson provided a St. Paul FBI agent with the name of the student president of the American Student Union. It was the year he retired. Eric Sevareid also had an FBI file, and his student activism was included in it, as was that of his fellow student activists Robert Loevinger and Lester Breslow. The sources of information to the FBI were sometimes anonymous, but for Sevareid in particular, it read much like Chase’s sketch of him. Breslow’s file indicates that a letter had been sent by Edward E. Nicholson in 1942 to the Special Agent in Charge concerning “the subject matter of the letter,” which was Lester Breslow. Even after Nicholson’s retirement, the FBI report noted that he was an important contact.Eric Sevareid’s FBI file is referenced in the Wikipedia entry for Sevareid. The entry refers to his declassified file from 1966 and discusses his on-campus associations at the University of Minnesota. Wikipedia, s.v. “Eric Sevareid,” accessed July 14, 2019, wikipedia.org/wiki/Eric_Sevareid. Robert Loevinger’s FBI file was accessed by his son Neal Loevinger and made available to the author by him. Lester Breslow’s FBI file was accessed through The Black Vault, July 14, 2019, accessed June 19, 2023, https://documents.theblackvault.com/documents/fbifiles/historical/lesterbreslow.pdf.

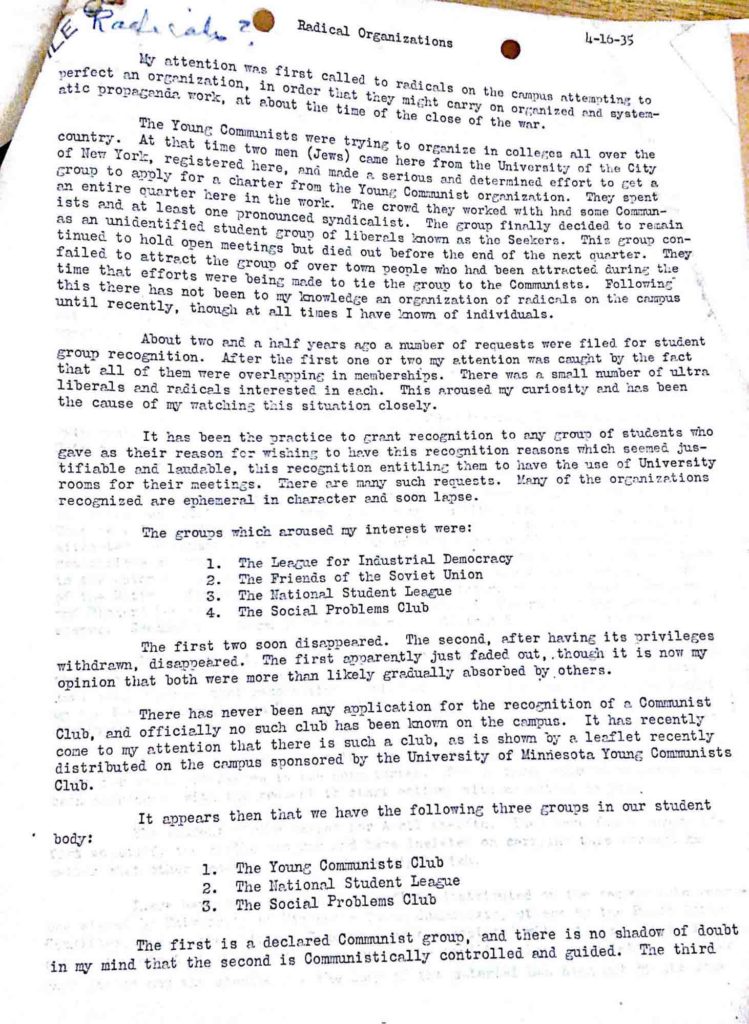

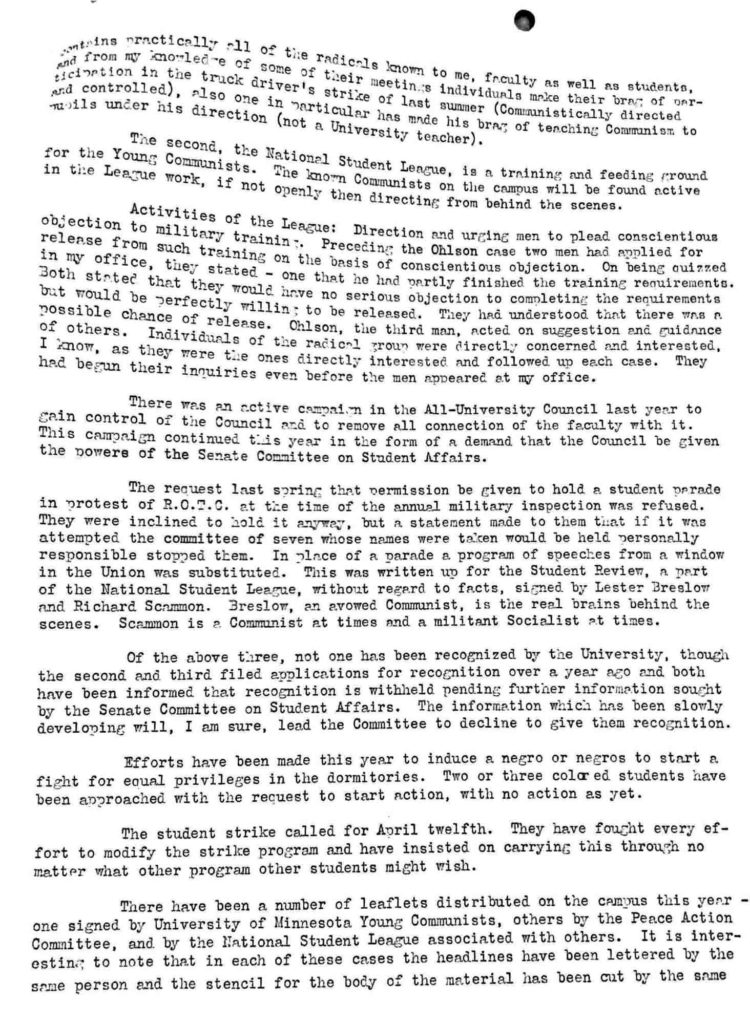

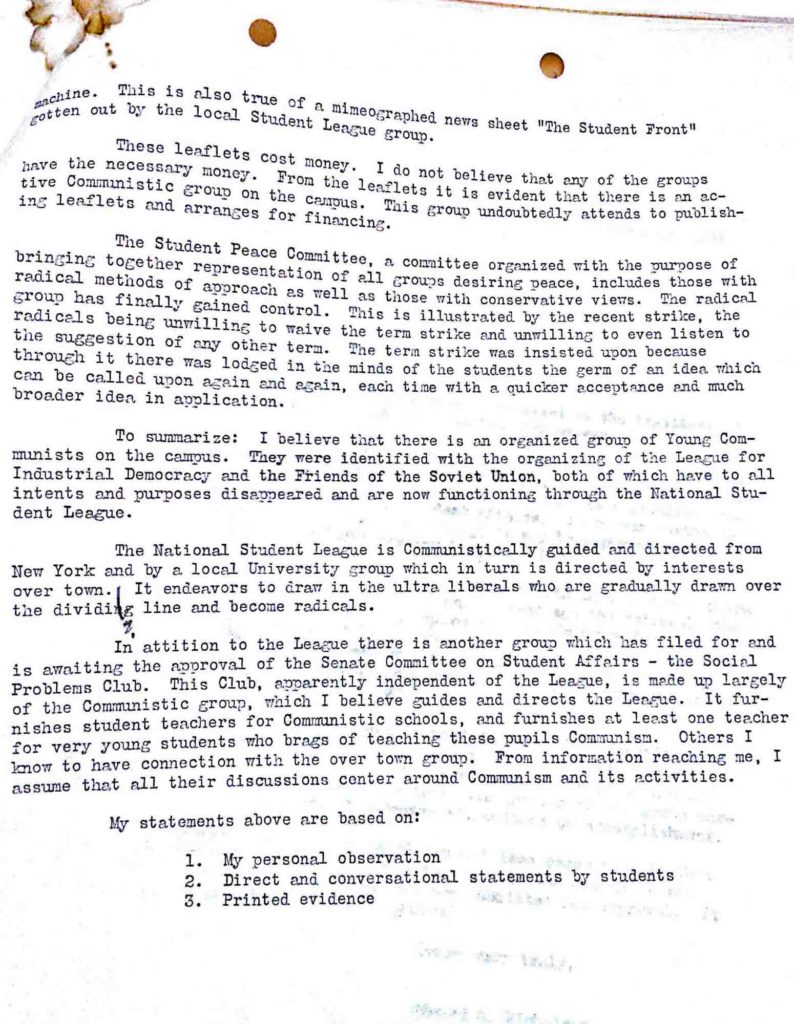

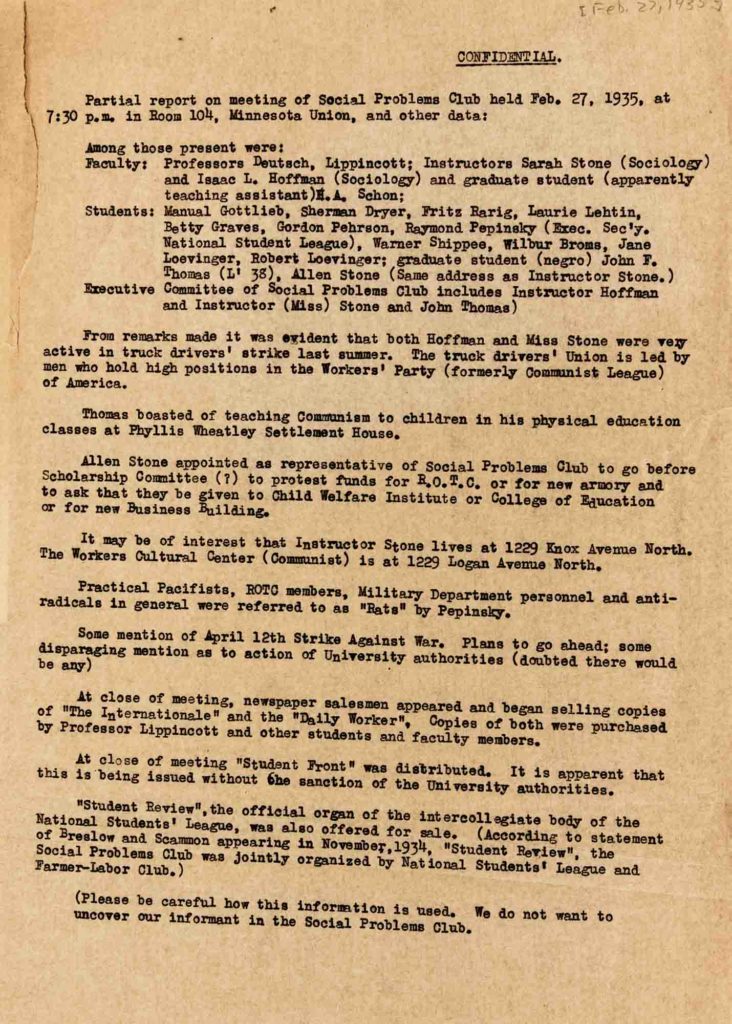

In 1935, Dean Nicholson wrote a report for his own files laying out his version of the history of radicalism at the University of Minnesota as well as a very detailed analysis of how communism influenced each group. Some of the students he labeled Communists were not, as described in their own memoirs or articles. Nicholson suggested that African American activism about integrating student housing was initiated by Communists. It was not, as detailed in the essay for this website which documents the leadership of the movement “Segregated Student Housing and the Activists Who Defeated It”. He railed against student use of the term “strike” in their anti-war demonstration, which revealed his own Law and Order Forum anti-labor politics. Finally, he noted that a member of the Social Problems Club taught young children about communism, a fact that appears in an “undercover” report in the Chase files dated the same month as Nicholson’s own report “Radical Organizations.” It seems clear that Dean Nicholson is the person writing directly to Ray Chase to admonish him to be careful to protect the source in that report. This wording is identical to a report he sent to President Coffman about the Seekers Club in 1921.

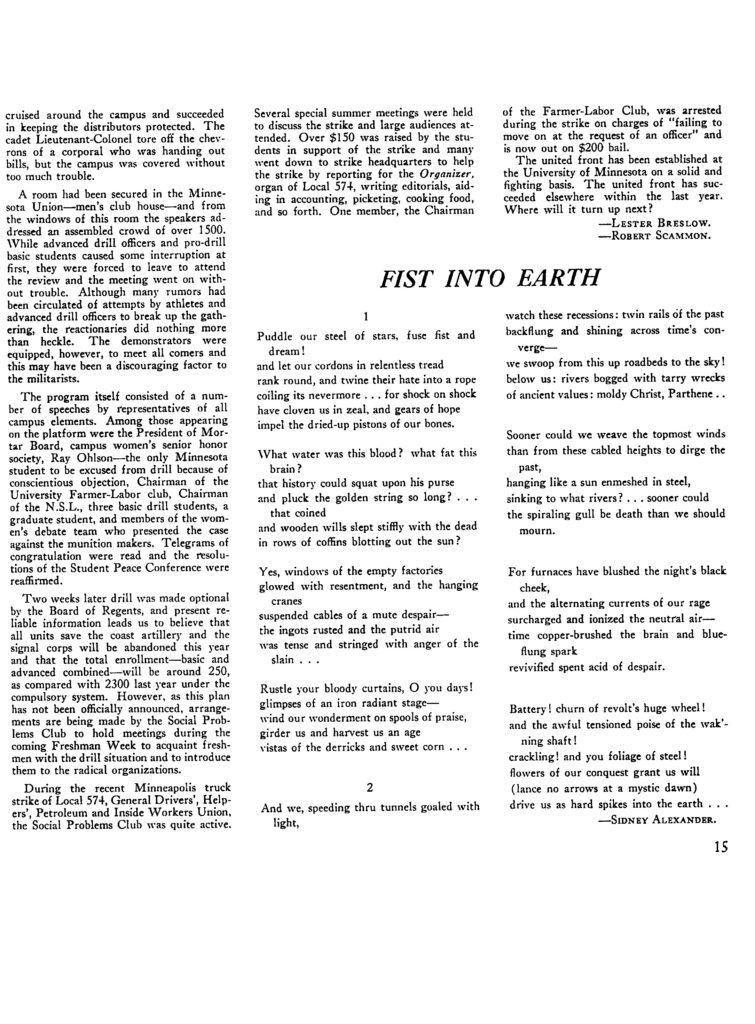

The very students that he attacked documented their own experiences of their activism. Two of those students were Lester Breslow and Richard Scammon, among the most vilified by Nicholson, and thus Chase. In their description of how students built a successful social movement in 1934 they focus on the diversity of their ideas and the alliances that they built as students deeply concerned with social change. Their brief article in the Student Review is a rich description of how they created that movement, which emphasized their political diversity and Dean Nicholson’s efforts to thwart them.

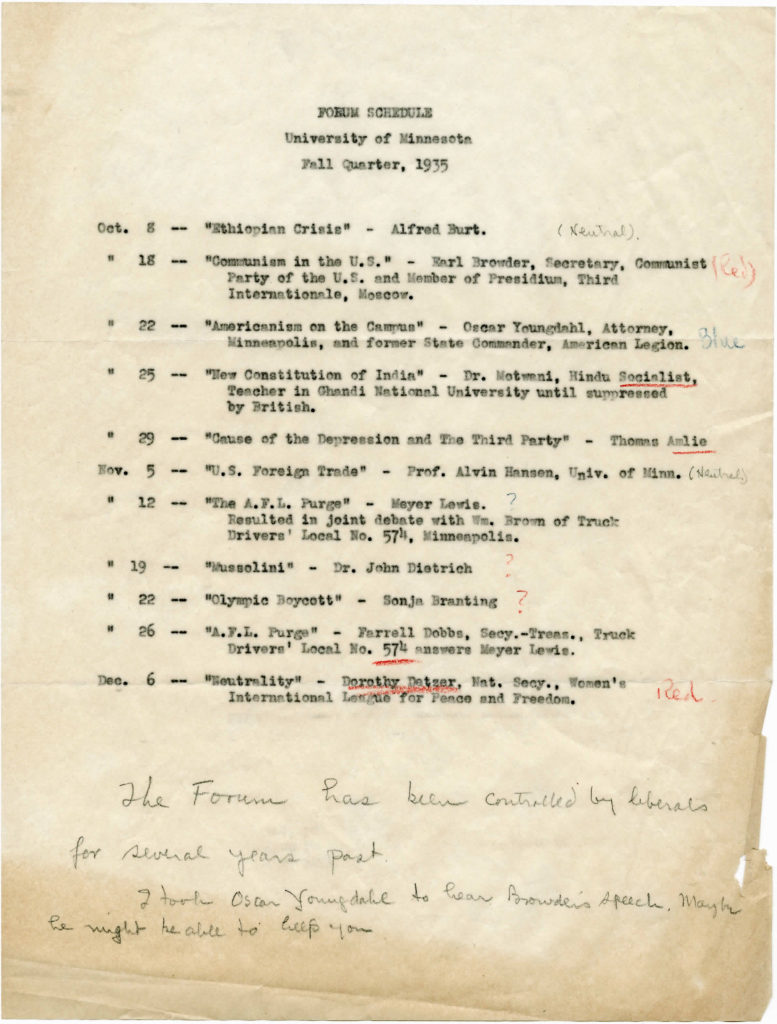

Ray Chase’s files include many lists of campus speakers during the 1930s. He carefully monitored who spoke at the University of Minnesota as an important weapon in his arsenal to be used to prove that the University of Minnesota harbored Communists. He did this for two reasons: he sought to censor any open exchange of ideas, and he argued that public funds were being misappropriated by paying people with whom he disagreed.

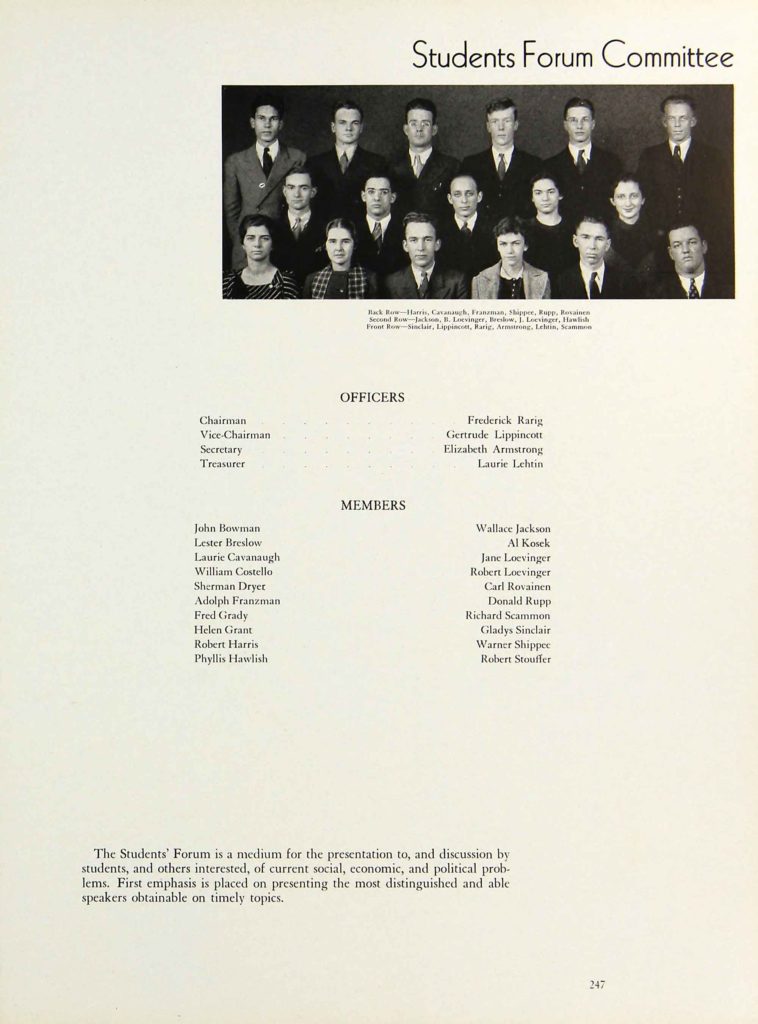

The Student Forum was the organization that invited a variety of speakers to campus. The members of the Student Forum were included in the Gopher yearbook each year. More than one-third of the names of members of the 1935 Student Forum appear on Ray Chase’s lists of radical and politically suspect students. The names of the speakers invited to campus that year are also in his files. Dean Nicholson supervised the organization, knew the students, and is likely the link between Ray Chase and this information. Nicholson did not censor the students. Instead, information about them and the guests invited to campus were sent to Chase, which he used to “prove” his claims of communist infiltration, which became part of his attacks on Farmer-Labor politicians.

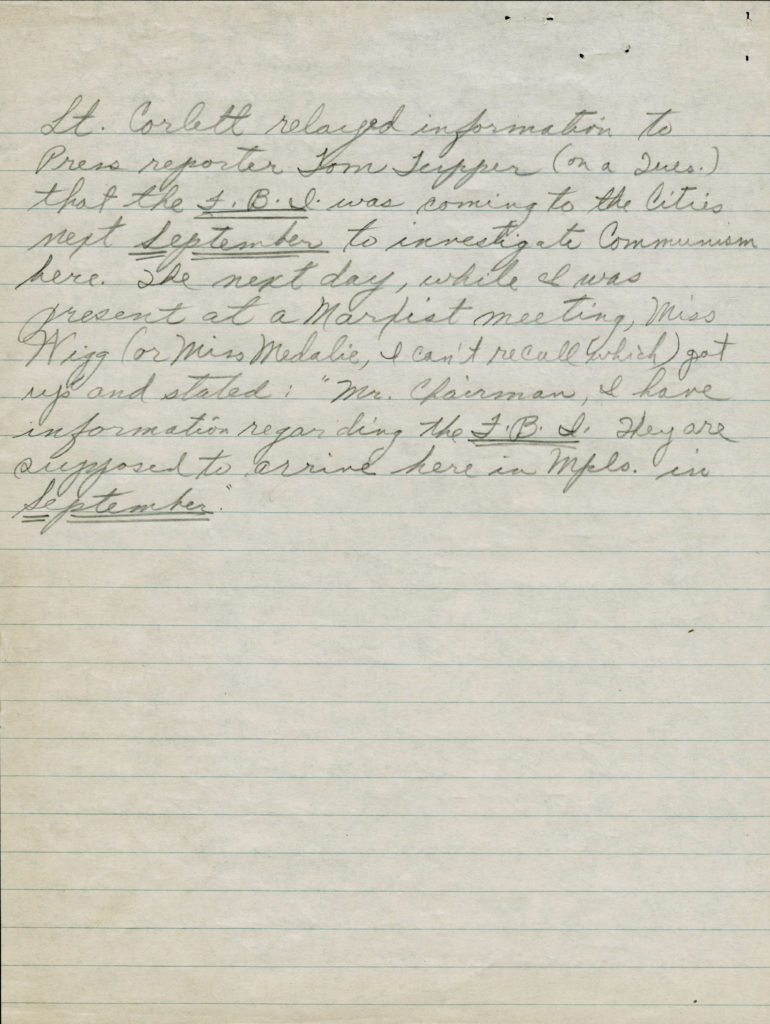

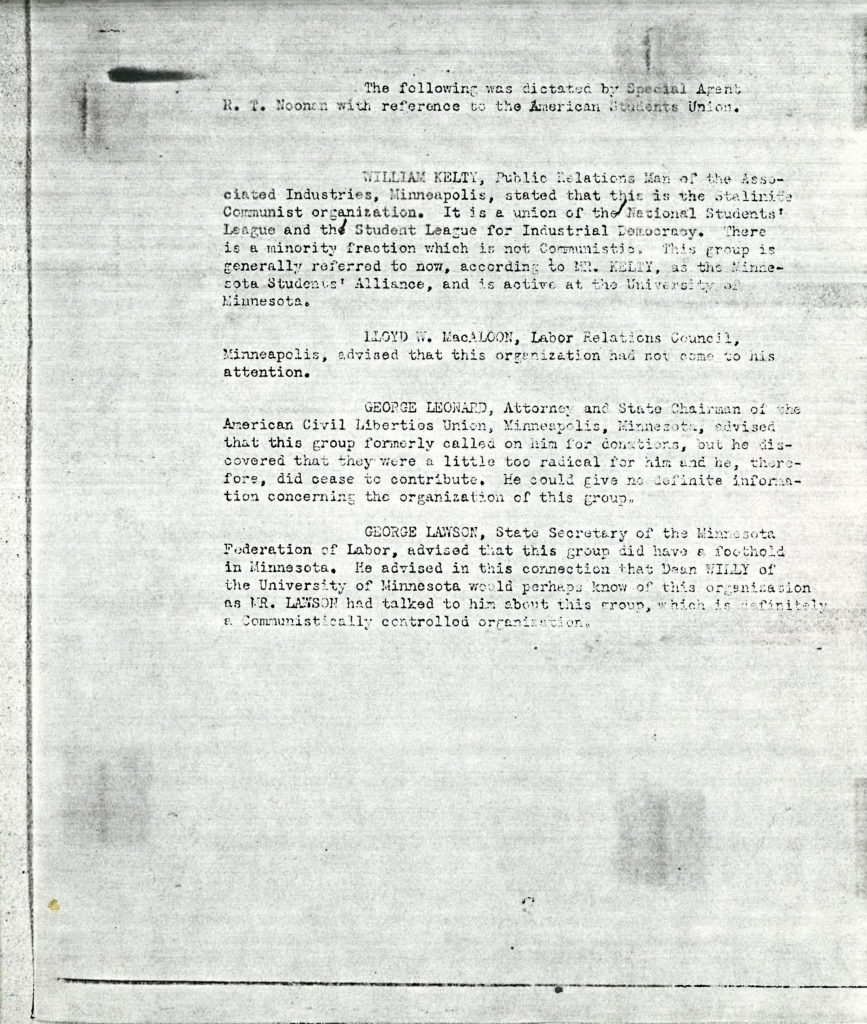

Lieutenant Colonel Adam Potts spied for Ray Chase when he recruited an unnamed person to join the Marxist Club in 1939 and the Socialist Club. Chase requested that Potts provide the “nationality” of students in order to learn whether they were Jews or had immigrant parents, both groups that he judged were outside the boundaries of “Keeping America American.”

Ray Chase also received information from others who spied on student political organizations. An anonymous description of a February 27, 1935 Social Problems Club listed all of those attending and the topics discussed. As noted above, it is nearly identical to the report authored by Nicholson the same month. Dean Nicholson’s files contain a report he wrote about radicalism at the University of Minnesota. He discussed the Social Problem Club with information that is remarkably close to this report in the Chase files. Dean of Students Papers, April 16, 1935, Box 10, Folder 35, Radical Organizations and Activities Re. Communism, University of Minnesota Archive.

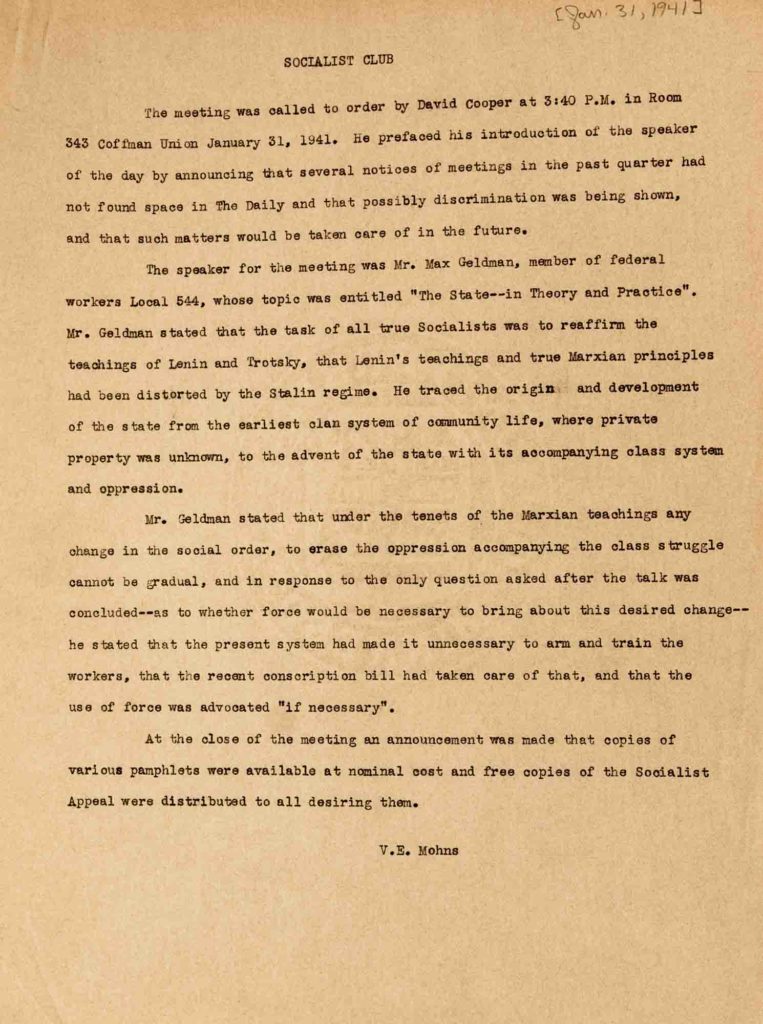

Vern Mohens, who signed his name to a description of a meeting of the Socialist Club in January of 1941, worked with Nicholson. He was also the administrator who, in 1942, closed a cooperative student house, the International House, when he learned it was racially integrated as discussed in the essay for this website “Segregated Housing and the Activists who Defeated It”.

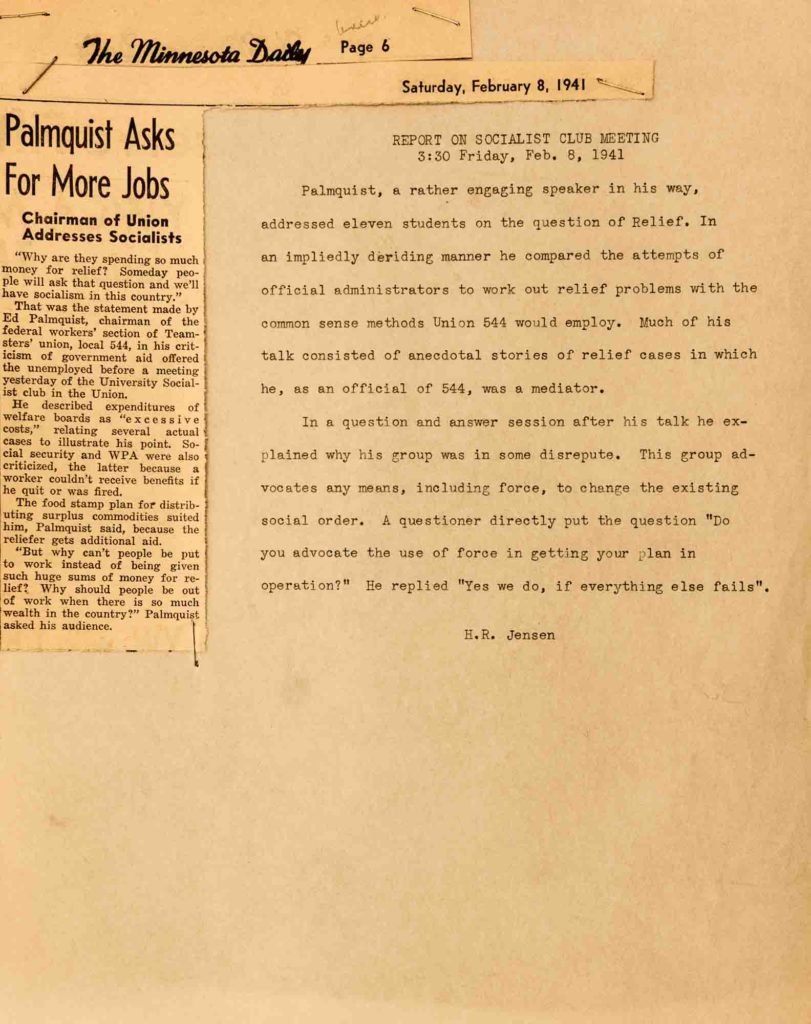

H.R. Jensen provided notes that were sent to Ray Chase on the Socialist Club meeting the following month, and the Minnesota Daily article about it was stapled to it. Nicholson described sending Daily articles to Chase in their correspondence.

J. Edgar Hoover (1895–1972) built the FBI as a powerful espionage agency.Beverly Gage, G-man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century (New York: Viking, 2022); Tim Weiner, Enemies: A History of the FBI (New York: Random House, 2012).

Hoover’s obsession with communism led him to doggedly pursue left-wing student activists for his entire career. He began his pursuit of Communists in the United States as a result of a confidential meeting made with President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1936 in which Roosevelt authorized him to spy on them, an activity that had been suspended after Americans revolted against the suspension of civil liberties in the early 1920s. Although Roosevelt also empowered Hoover to pursue Fascists, the threats of communism were much more broadly defined and pursued by Hoover than were the threats of Nazi spies.Gage, G-Man, 204-207.University and college administrators throughout the United States eagerly cooperated with the FBI, just as Edward Nicholson did when he gave the chair of the University of Minnesota American Student Union Esther Leah Medalie’s name (misspelled on the report) to the FBI. Nicholson and Chase’s surveillance consistently tracked with J. Edgar Hoover’s pursuit of those he defined as Communists.Robert Cohen, When the Old Left Was Young: Student Radicals and America’s First Mass Student Movement 1929-1941 (New York: Oxford Press 1993).

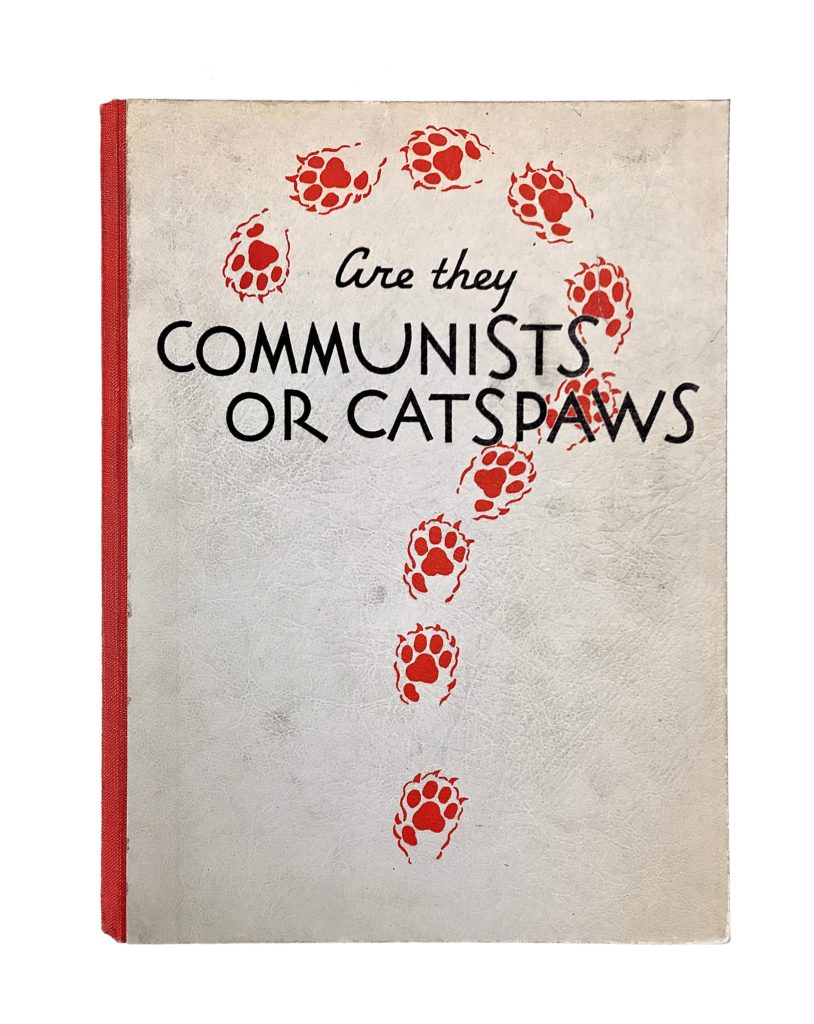

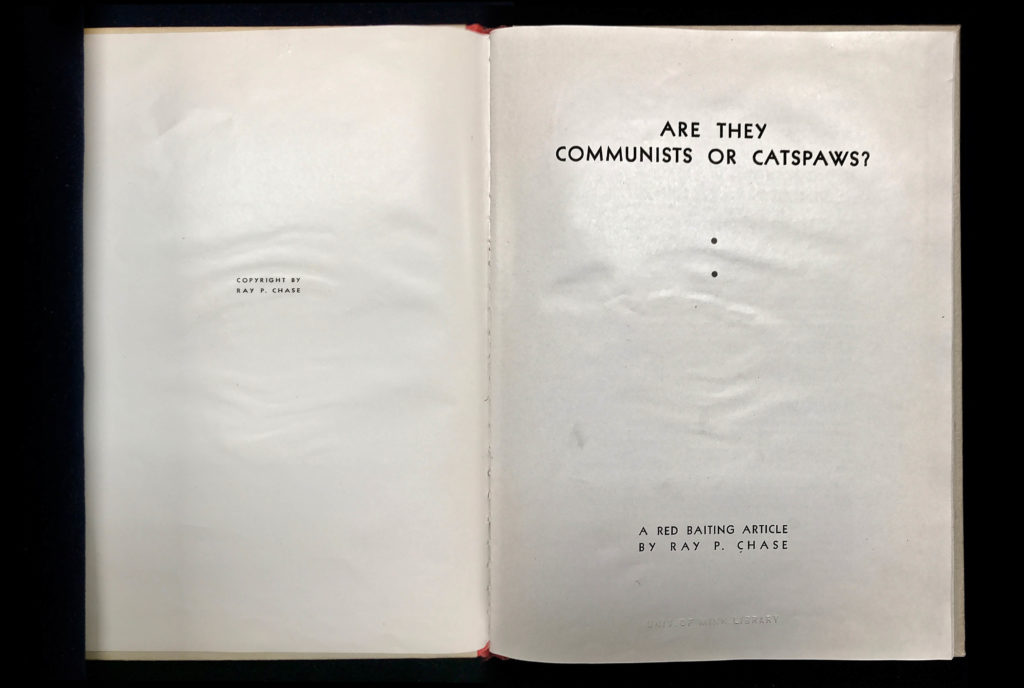

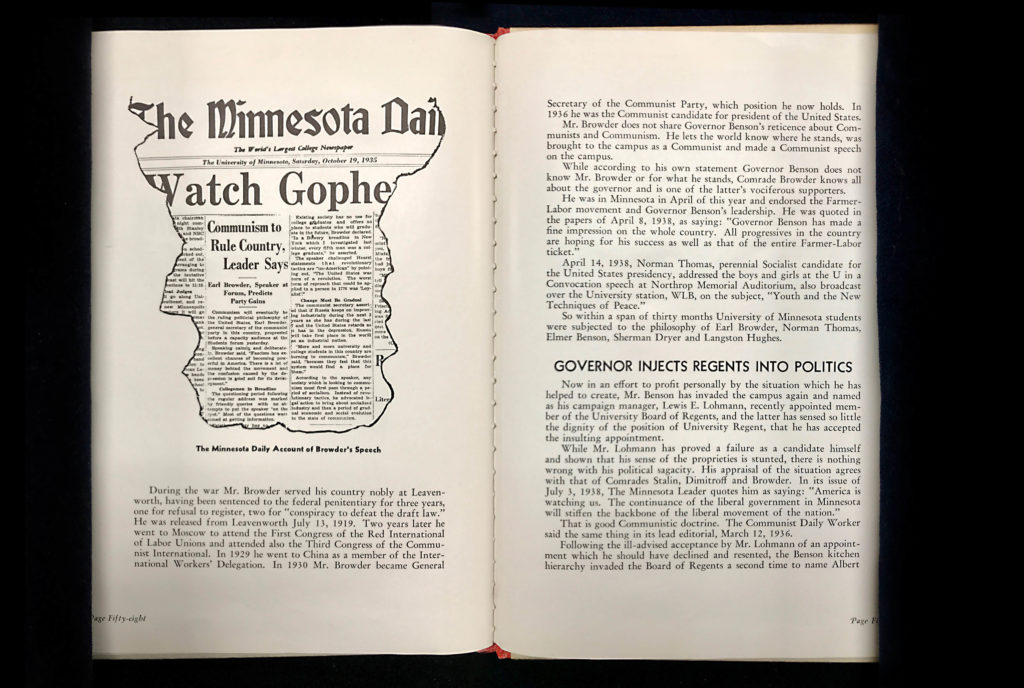

The Role of Campus Surveillance in Minnesota’s 1938 Election

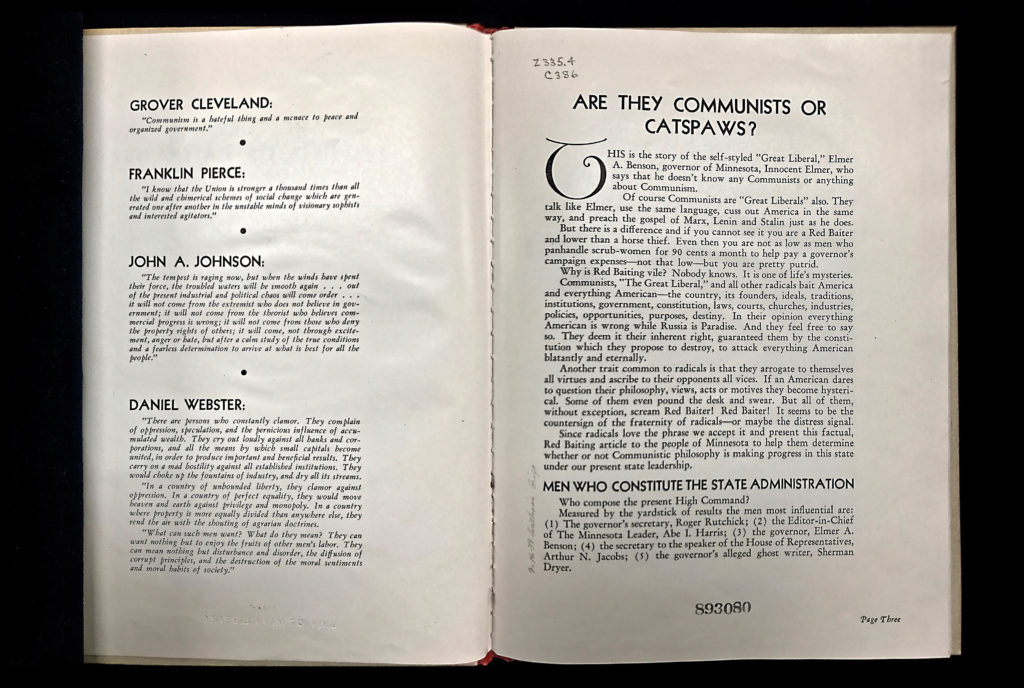

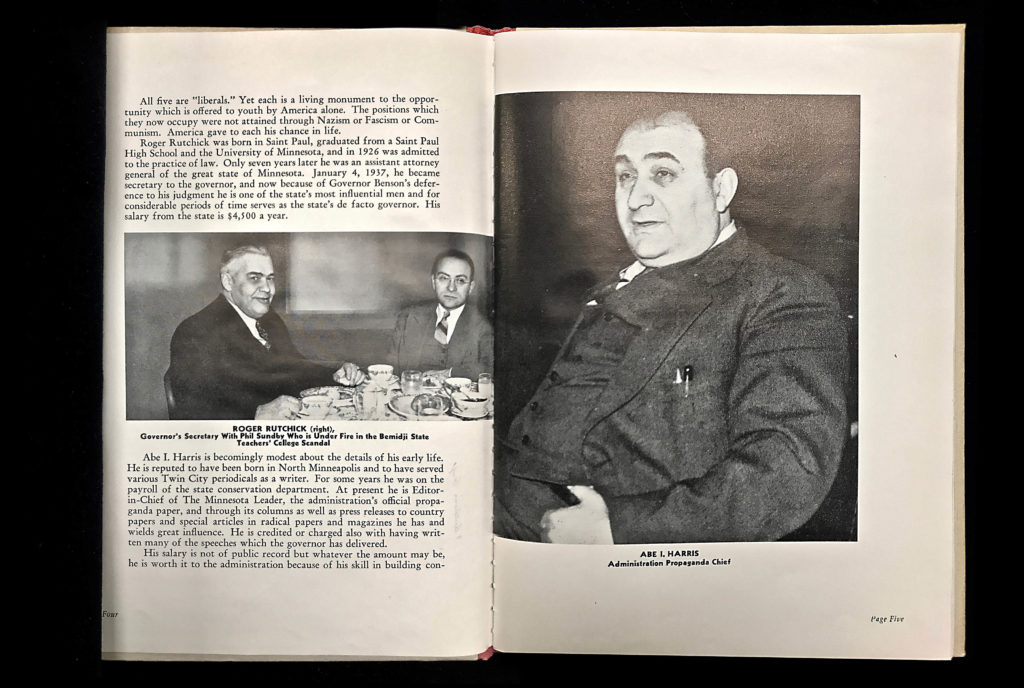

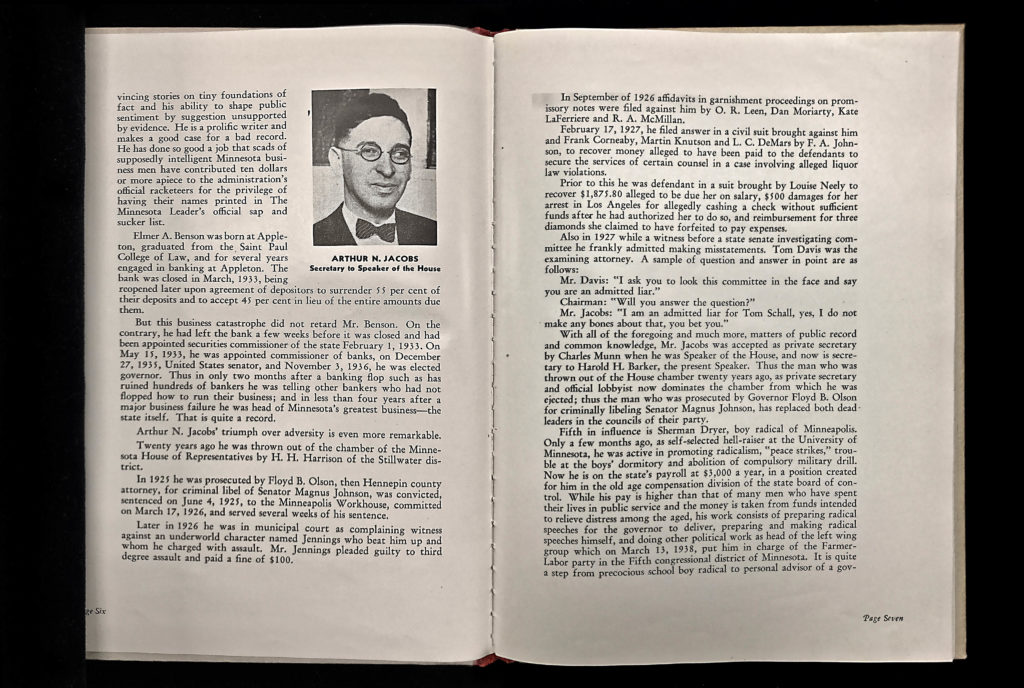

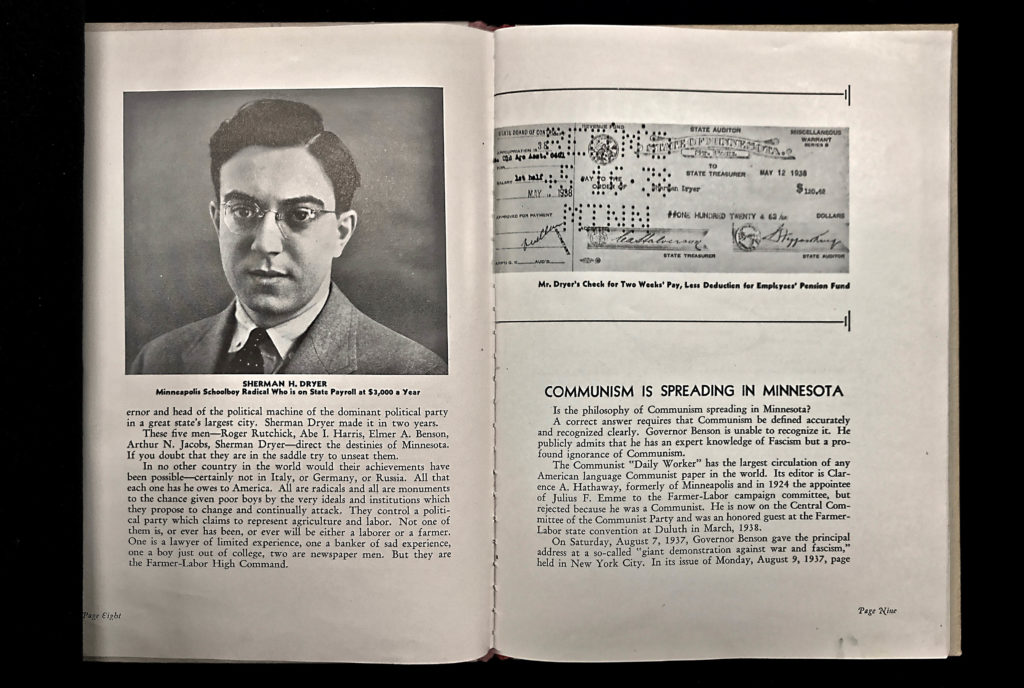

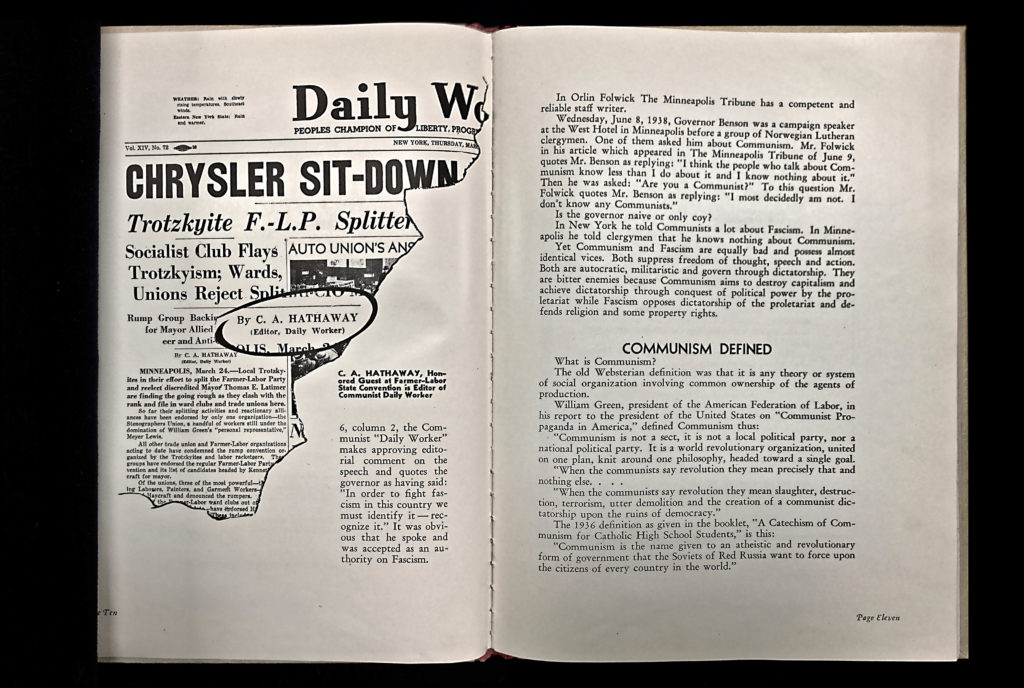

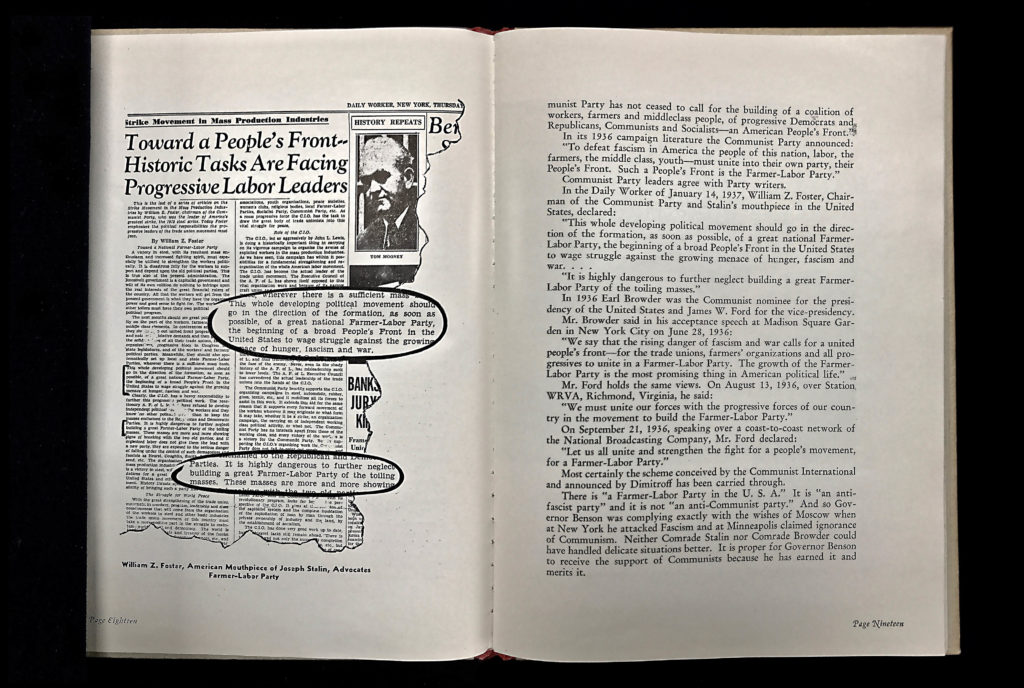

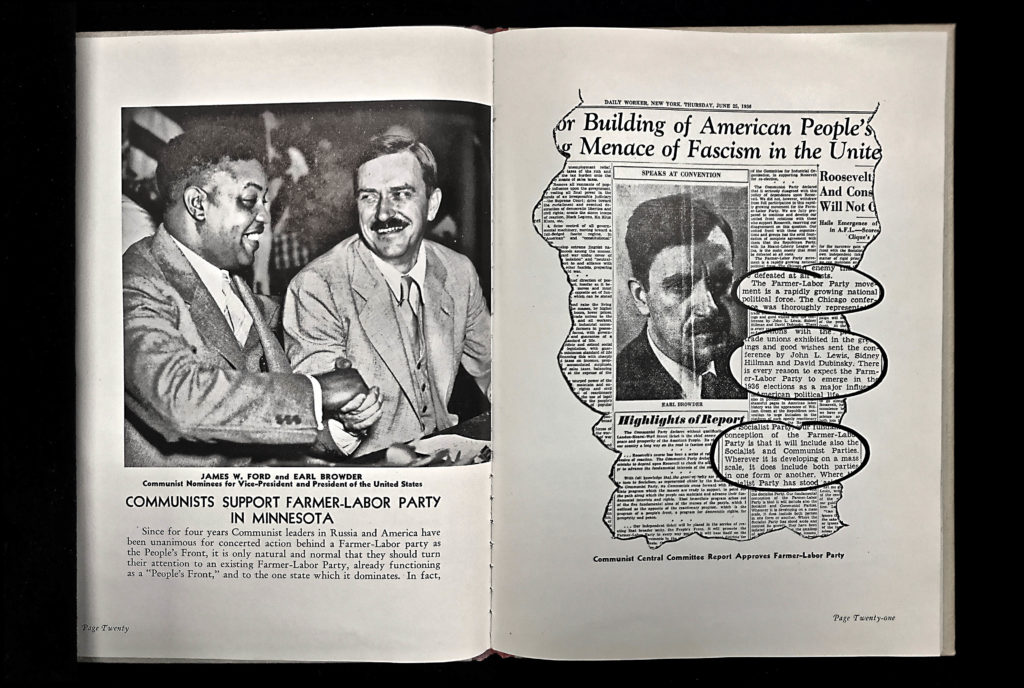

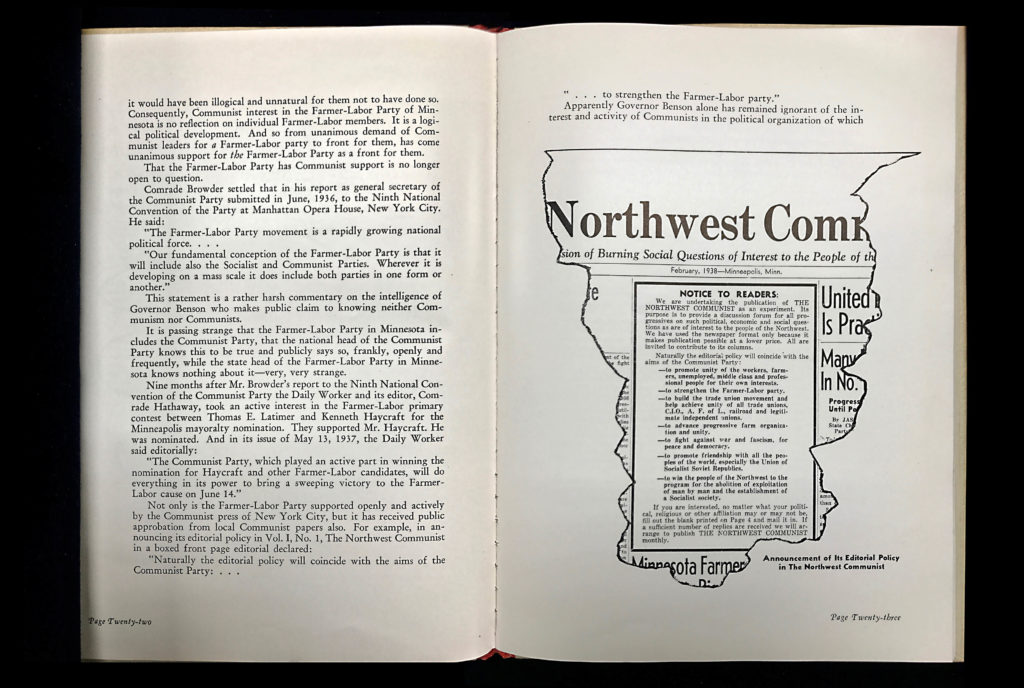

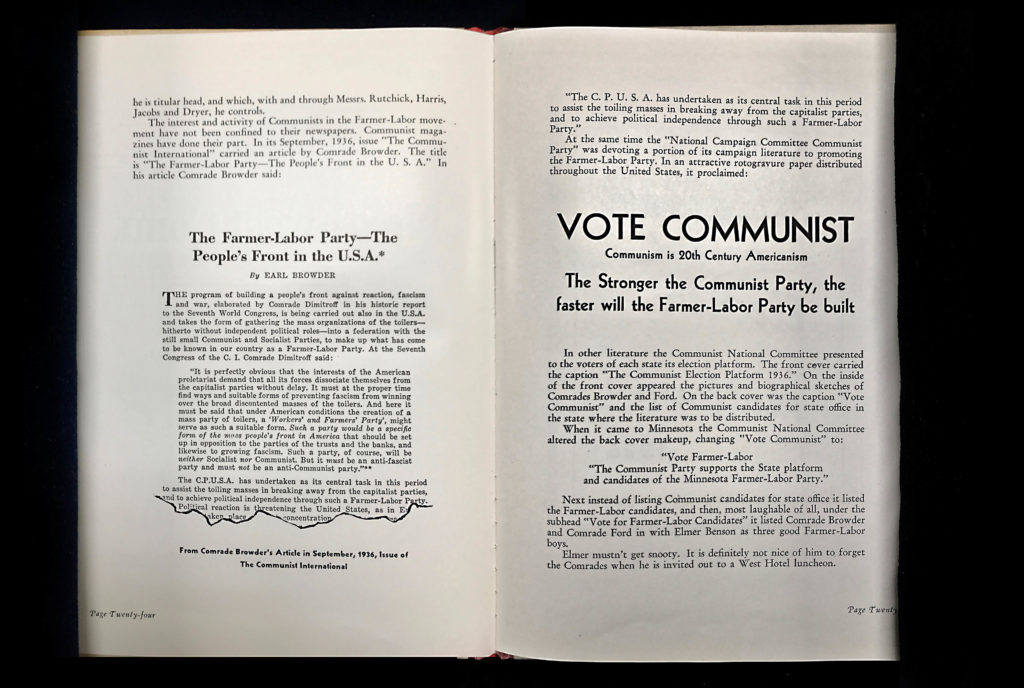

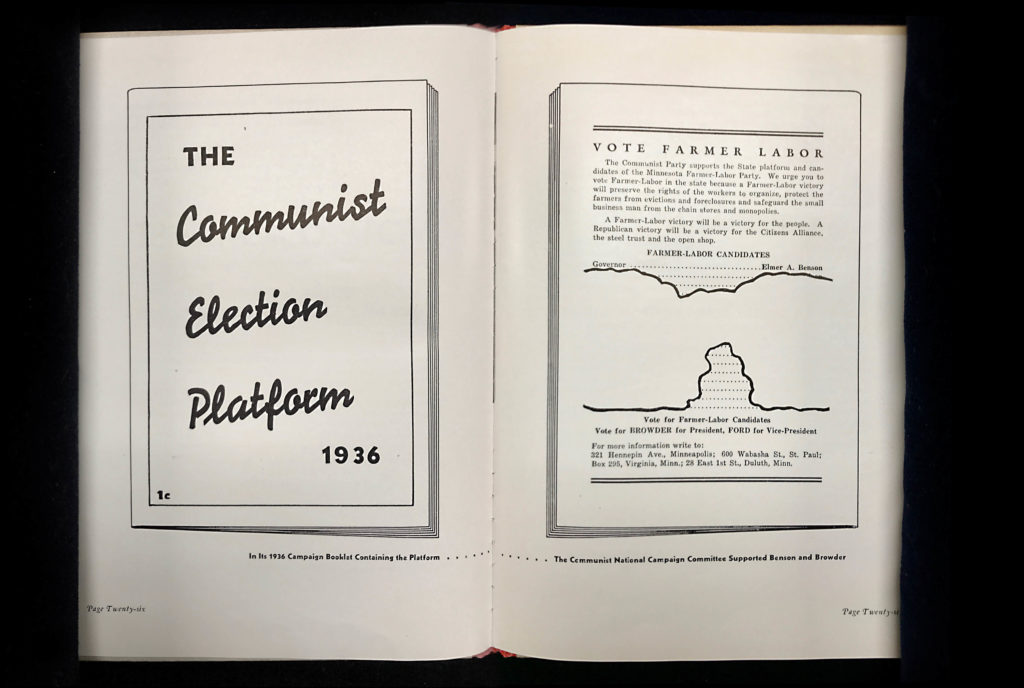

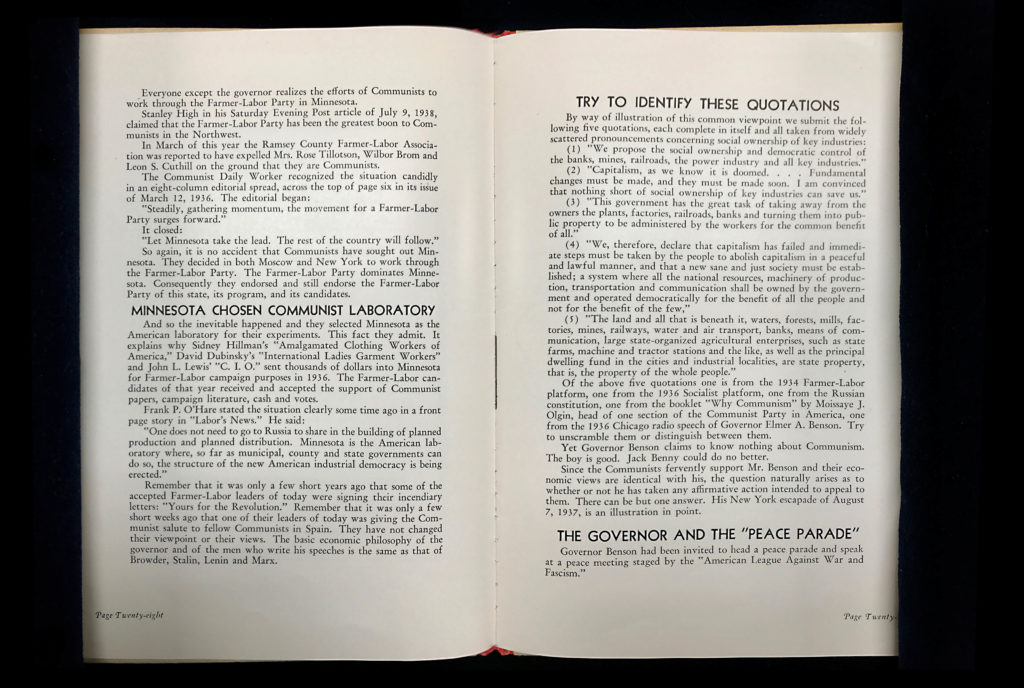

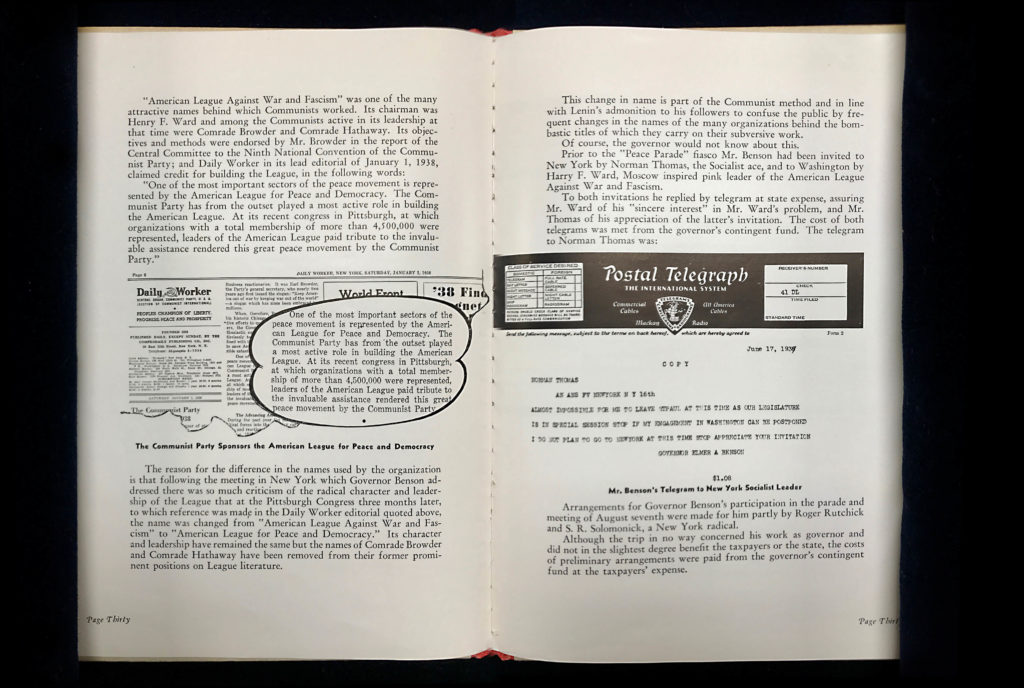

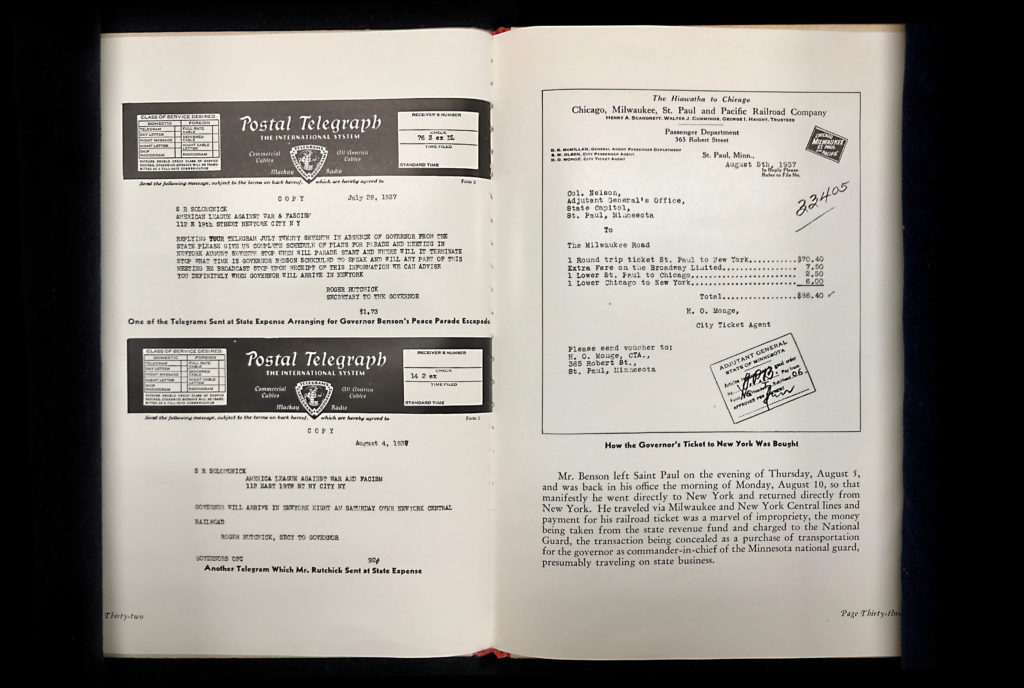

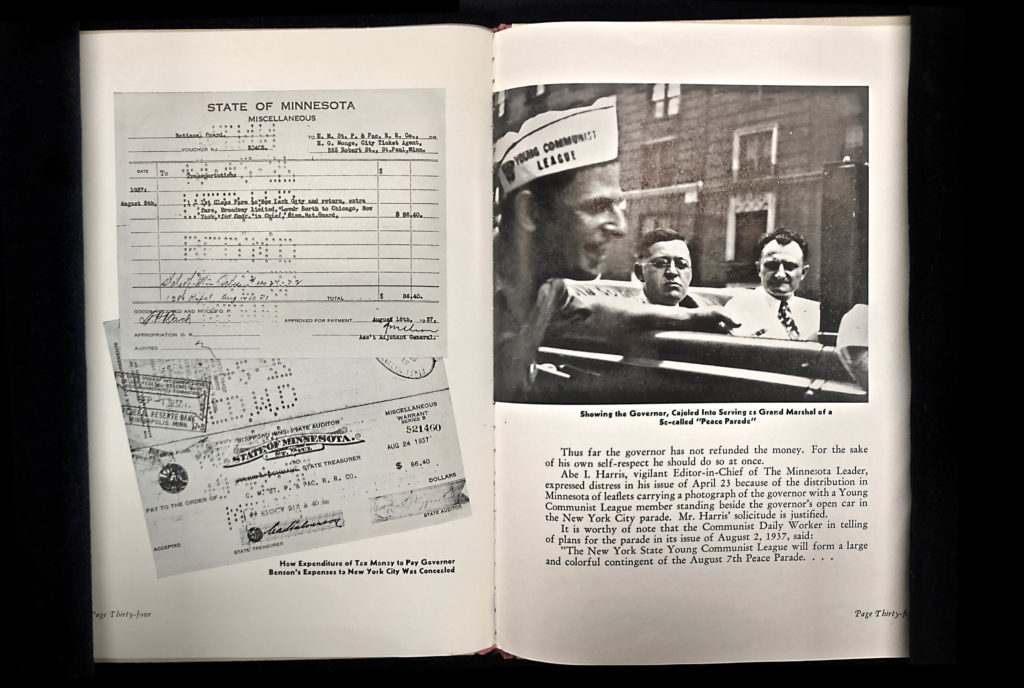

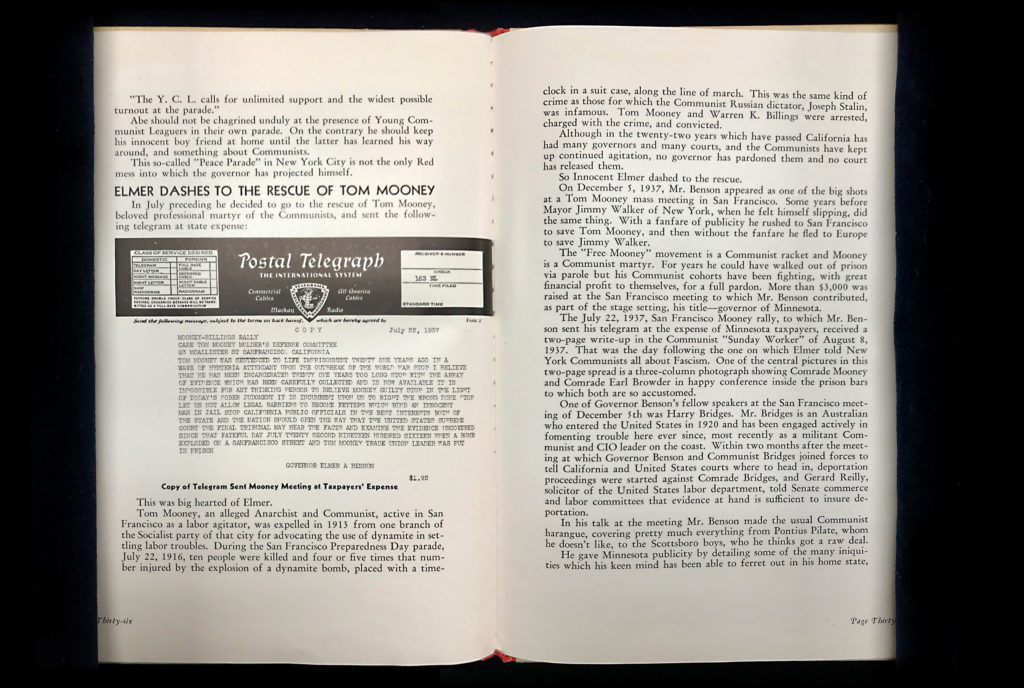

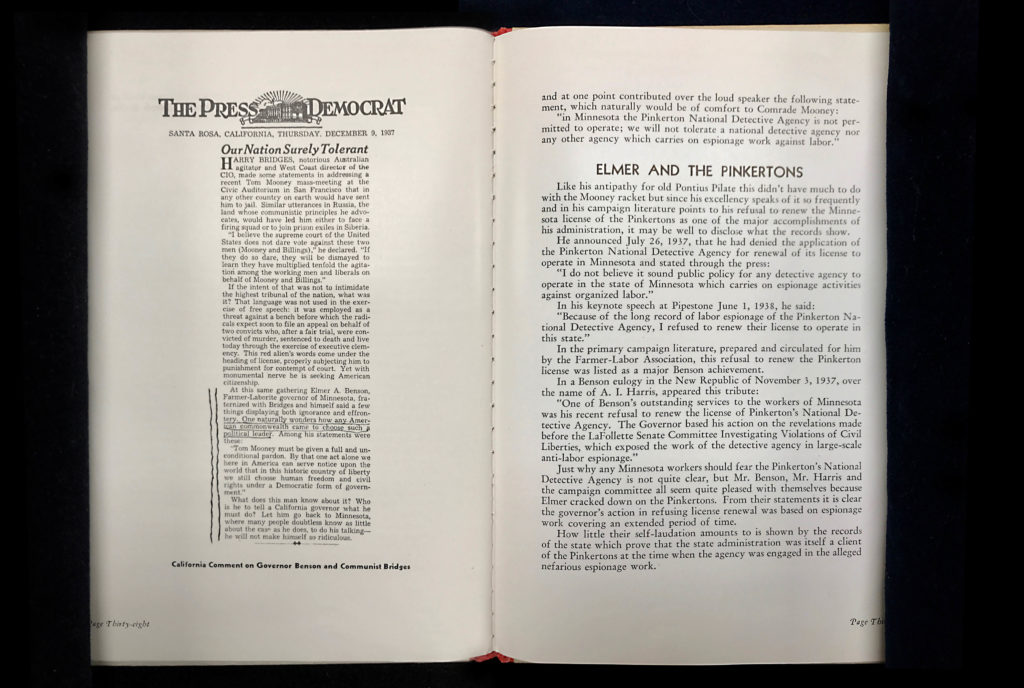

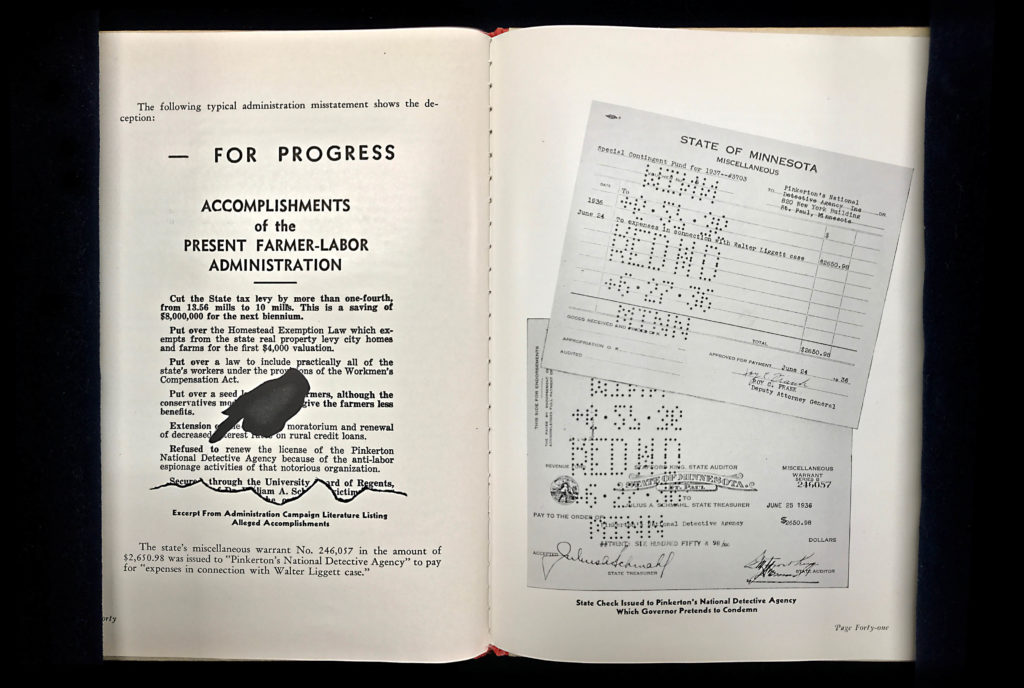

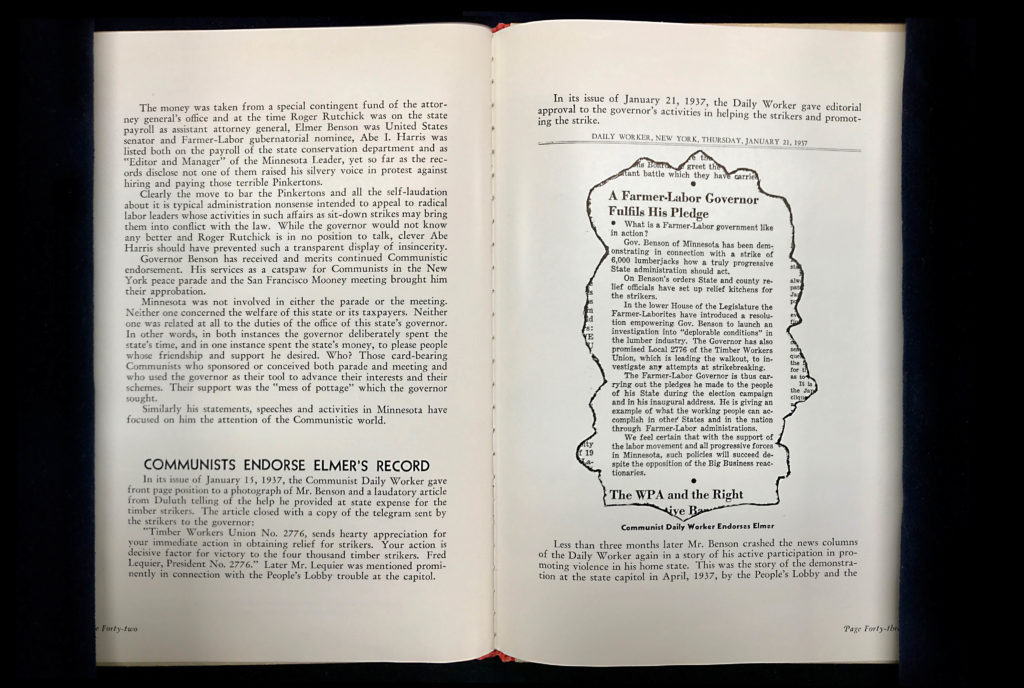

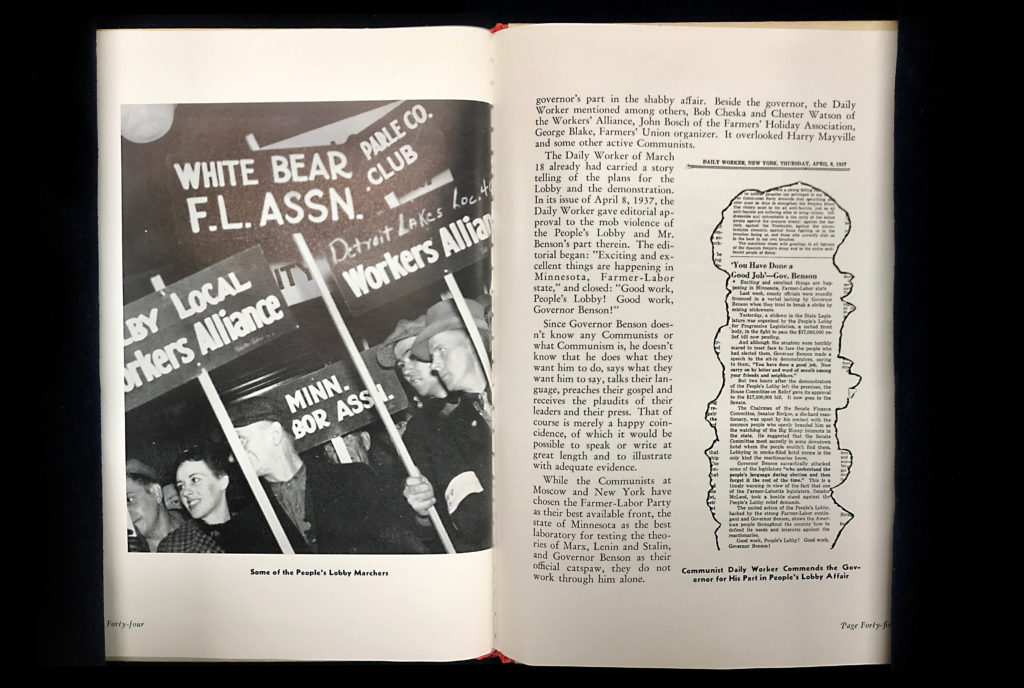

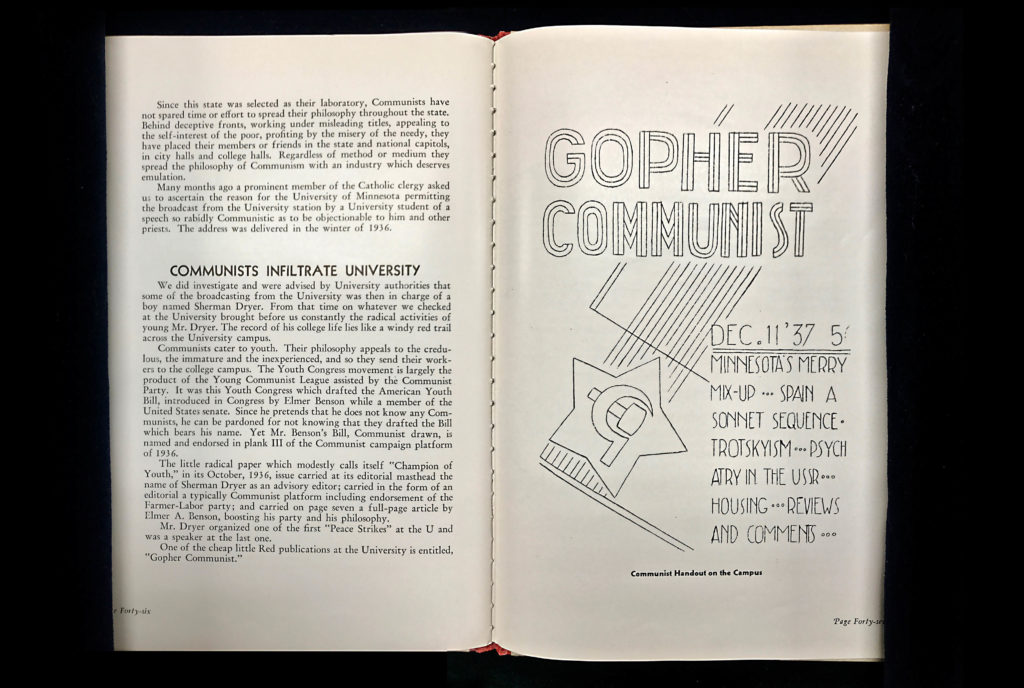

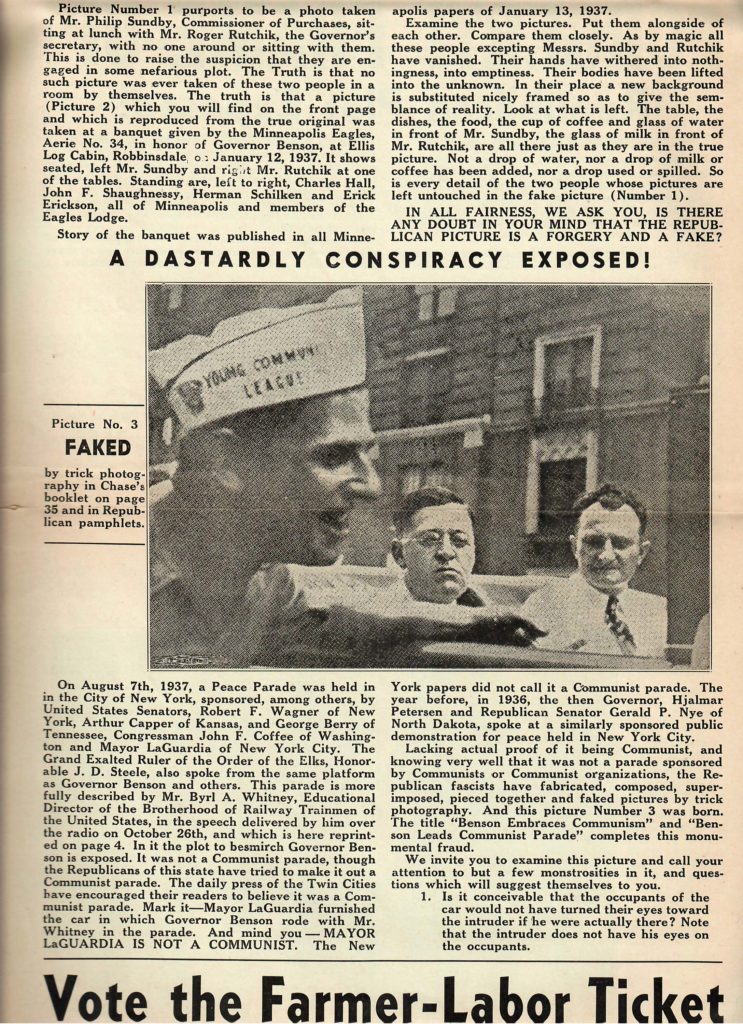

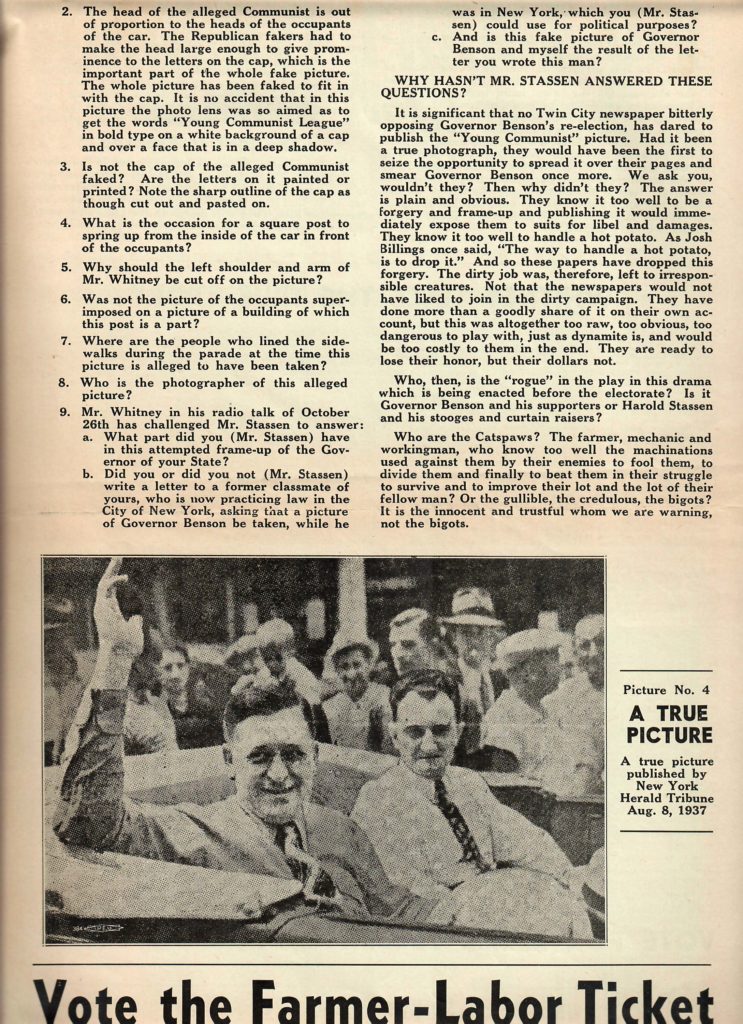

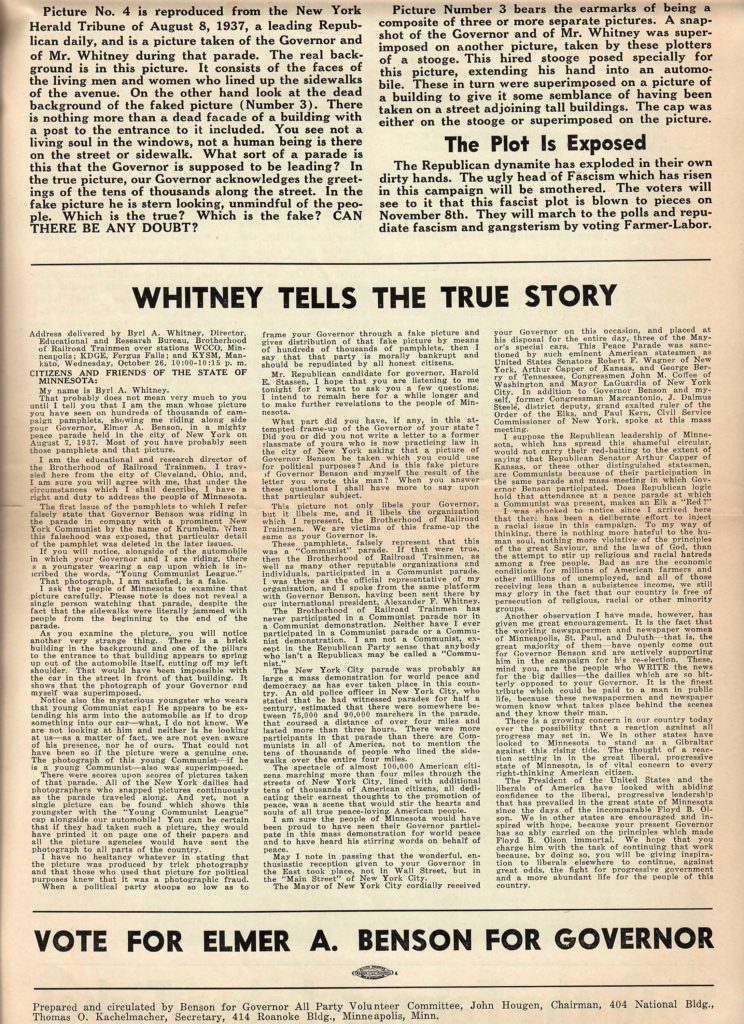

Some of the surveillance that Ray Chase requested from Dean Nicholson and others appeared in his self-published, professionally produced, 62-page hardcover booklet the month before the 1938 gubernatorial election between Farmer-Laborite Elmer Benson and his Republican challenger Harold Stassen. It was titled Are They Communists or Catspaws: A Redbaiting Pamphlet. A “catspaw” is a term that describes a person used unwittingly to accomplish another’s goals. Governor Benson, Chase implied, was being used by “Jews and Communists” in his inner circle. Chase estimated that he sent 13,000 copies of his so-called pamphlet by mid-October to every legislative candidate and all Conservative Christian clergy. Communists or Catspaws was widely discussed in the Minnesota press, and religious and political leaders publicly supported or condemned it. It had an impact on the election, which Stassen went on to win handily. Chase used false information, innuendo, and altered photographs, and wrapped them all in the claim they were “factual.”Discussions of the pamphlet and its impact on the 1938 election may be found in Arthur Naftalin, “A History of the Farmer Labor Party of Minnesota” (PhD dissertation, University of Minnesota, 1945), 375-376; Richard Valelly, “State-Level Radicalism and the Nationalization of American Politics: The Case of the Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party” (PhD dissertation, Harvard University, 1985), 260-261, University Microfilms International, Ann Arbor, Michigan; Steven J. Keillor, Hjalmar Petersen of Minnesota: The Politics of Provincial Independence (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society, 1987),164-167; William Millikan, A Union Against Unions: The Minneapolis Citizens Alliance and its Fight Against Organized Labor, 1903-1947 (St Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2001), 344. The lists of recipients of Are They Communists or Catspaws may be found in Ray Chase Files, Box 42, Undated 1938, Minnesota Historical Society. All of these scholarly studies underline the antisemitism of the pamphlet.

The pamphlet focused on who Chase claimed to be Benson’s close political allies and members of his administration. However, Chase did not mention or picture most of the significant people in the Benson administration. Rather, he focused on four men, all Jewish, two of whom played minor roles in Benson’s organization. Without using the word “Jewish” Chase mounted an antisemitic attack on Benson by suggesting that he was surrounded by Jews who were Communists, despite the fact that some of them had been vigorous in working against Communist infiltration of the Farmer-Labor Party. Chase included photographs of Jewish advisers that emphasized so-called Jewish facial features, such as large noses or obesity.Much of the antisemitism of Ray Chase’s “pamphlet” emerged from the primary fight for the Farmer-Labor Party nomination for Governor. Elmer Benson was challenged by Hjalmar Petersen. Historian Steven Keillor argues that Petersen did not stop those in his campaign who were overtly antisemitic even if he was not. The antisemitic attacks created by the Petersen organization in the primary were taken up by Chase and fueled his “whisper” campaign against Benson in the general election. Steven J. Keillor argues that Ray Chase’s Research Bureau began its attack against Governor Benson by investigating “wasteful spending.” However, by the spring of 1938, he focused on the “backgrounds” of Benson’s aids. Chase showed “great interest in identifying Jews in the liberal ranks,” a cue he took from the Farmer-Labor primary campaign. The research by Chase’s assistant resulted, he claimed, in finding links between Communists and Jews by means of the infamous forgery, The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion. Steven J. Keillor, Hjalmar Petersen of Minnesota: The Politics of Provincial Independence (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1987), 155-157, 163-164.

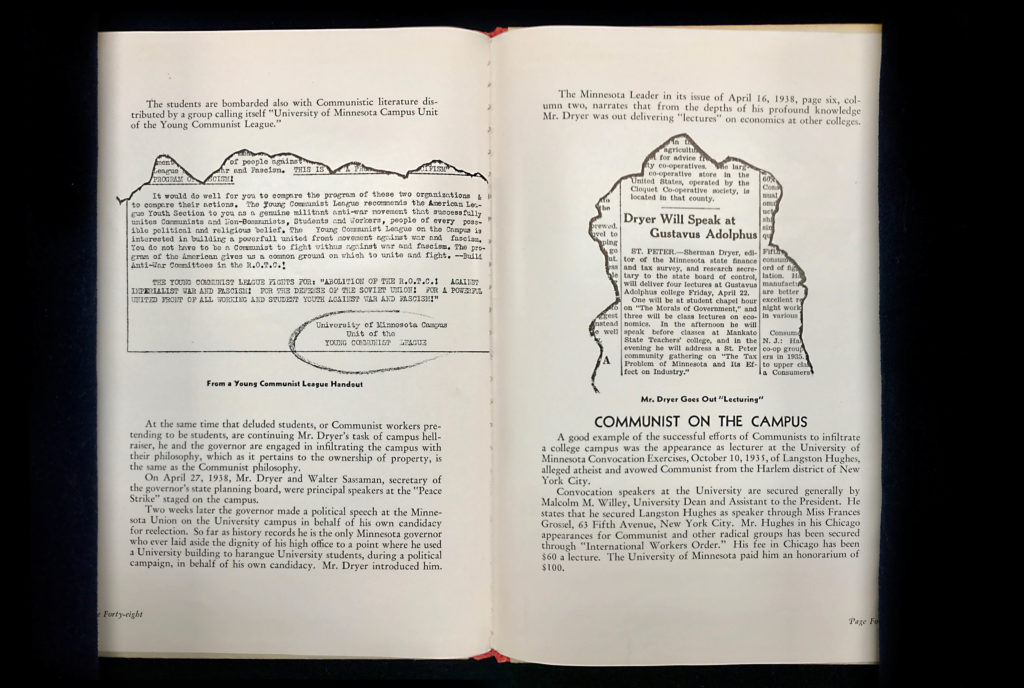

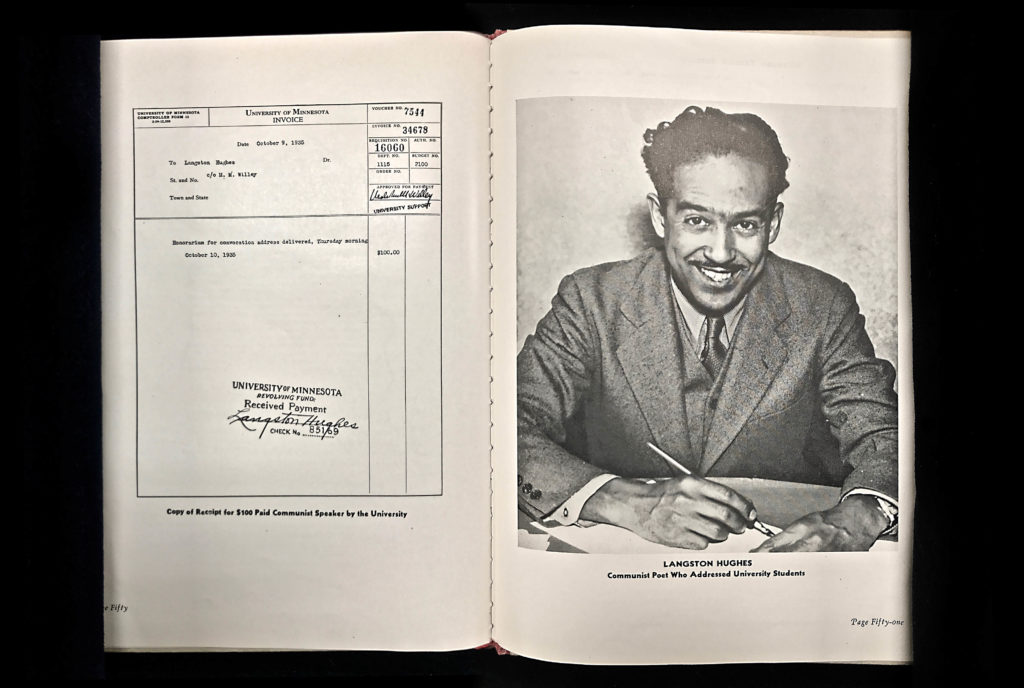

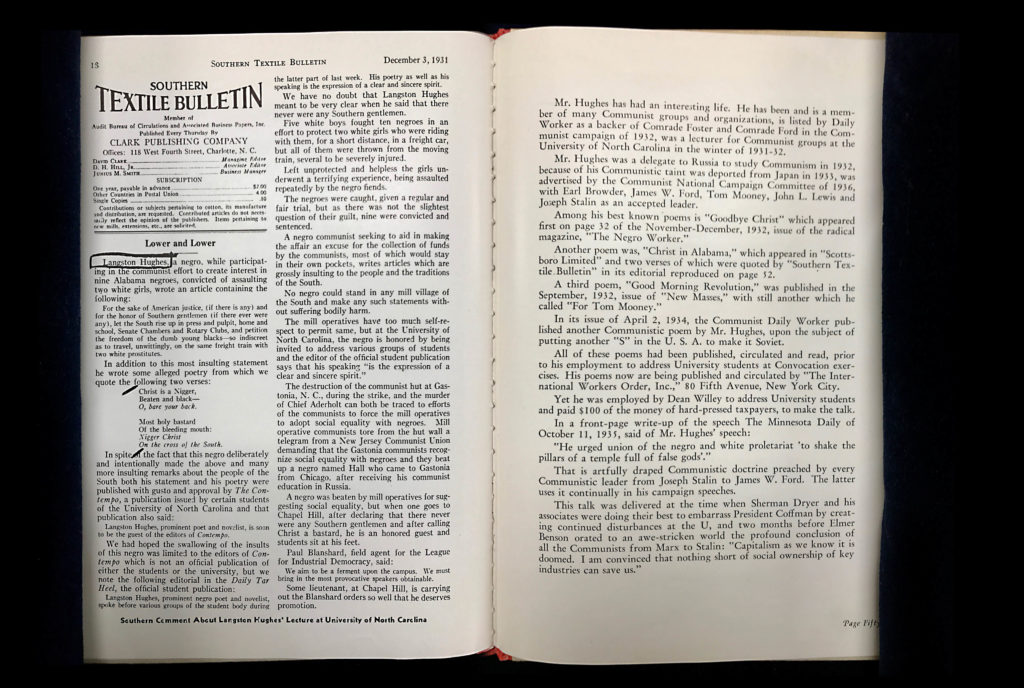

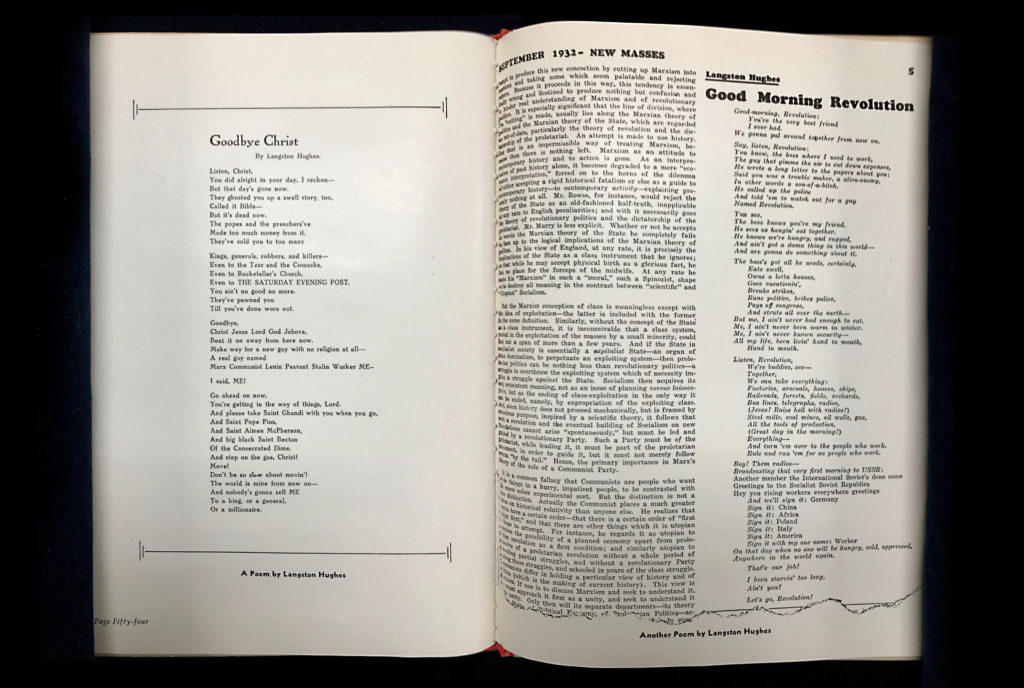

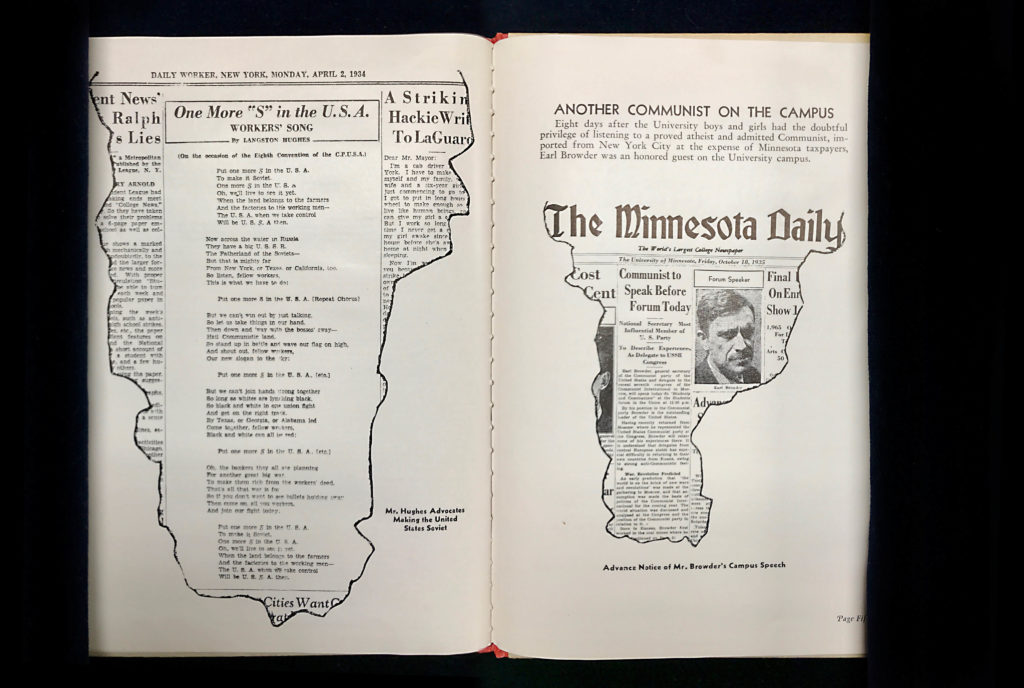

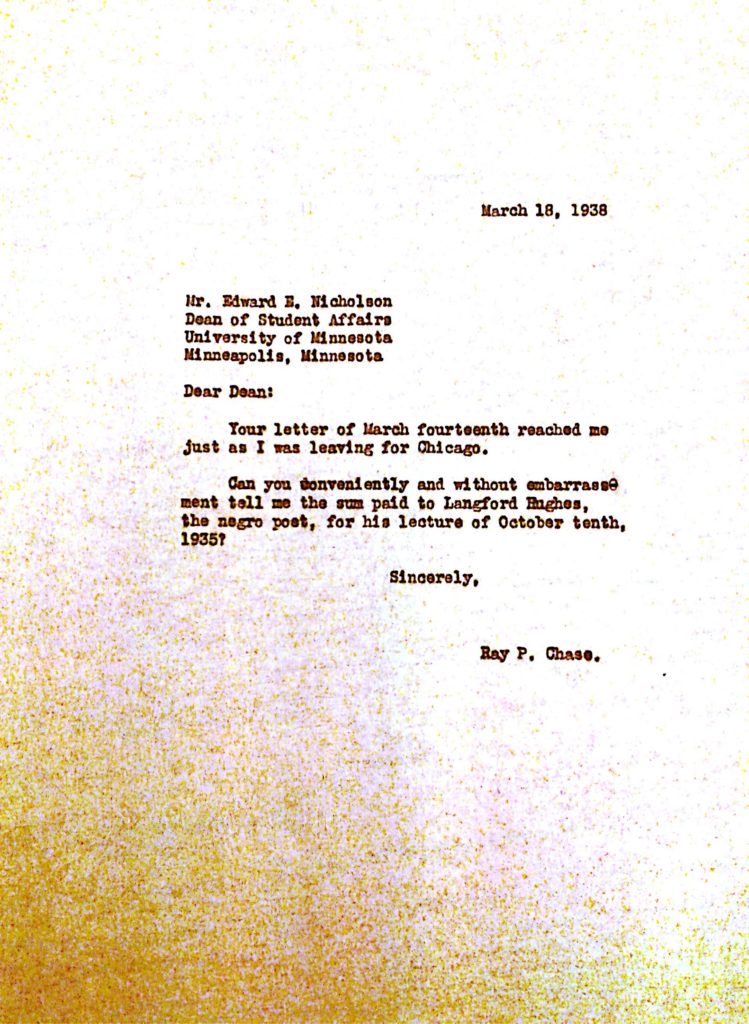

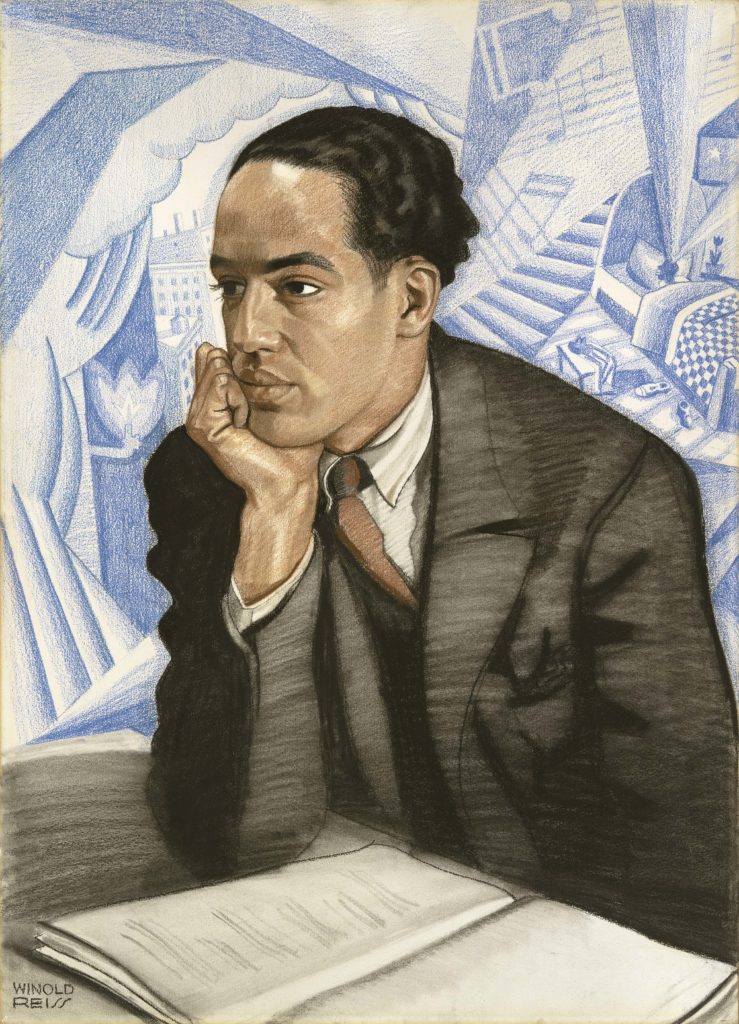

Many pages of the pamphlet were also devoted to the University of Minnesota. Sherman Dryer, who was included on Ray Chase’s “Radical Leaders” list, also appeared in it. Chase devoted several pages to the poet Langston Hughes, who was a convocation speaker at the University of Minnesota in the fall of 1935. Hughes spoke at the University’s opening convocation to an unprecedented 4,000 people in Northrop Auditorium, and his talk was broadcast by radio. He also lectured at the St. Paul YWCA, sponsored by the City-Wide Interracial Committee of St. Paul, and at the Citizen’s Aid Building, sponsored by the Interracial Committee of the Urban League.

By 1935, Hughes was a significant literary figure, a published poet, and novelist who had received a prestigious Guggenheim fellowship, among other awards. In the 1920s, he was a major and influential figure of the Harlem Renaissance, and went on to write for a large audience of Americans of many races and cultures. By the time of his death he had published and edited in every literary genre, including as a journalist.Arnold Rampersad, The Life of Langston Hughes: Volume 1: 1902-1941, I, Too, Sing America, 2nd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002) 313.

Langston Hughes was also a political activist throughout the 1930s concerned with the rights of African Americans and working people. During that period, he participated in causes led by the Communist Party, which he never formally joined. Over his life he was attacked by both the right and the left-wing for his ideas.

Chase tracked the fee that Hughes received with Nicholson’s help. Langston Hughes was included in Communists or Catspaws as further proof of the University’s domination by communism.

The Benson Campaign Responds

Christian Nationalism, Nativism, and Antisemitism in Minnesota Politics in the 1930s

Are They Communists or Catspaws was the tip of an enormous iceberg built of nativism, antisemitism, anti-labor movements, populism, and pro-Nazi and fascist politics. In Minnesota, it took the shape of false accusations about which Farmer-Laborites and others were Communists. Its ideas were driven by appeals to “America First” ideologies, which were born out of the “One Hundred Percent Americanism” of the WWI era that punished any form of dissent. That attitude was joined in equal measure to a nativist hostility to immigrants and their children that was energized by “scientific racism” and its attacks on people of color as well. “America First” weaponized an antisemitism that insisted that Jews were Communists and “internationalists,” as they were portrayed in Ray Chase’s pamphlet.John Higham, Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism 1860-1925 (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2022), 347, 382; Erika Lee, America for Americans: A History of Xenophobia in the United States (New York: Basic Books, 2019); Daniel Okrent, The Guarded Gate: Bigotry, Eugenics, and the Law that Kept Two Generations of Jews, Italians and Other European Immigrants Out of America (New York: Scribner, 2019).

Chase corresponded with the leaders of Minnesota’s most extremist and right-wing groups of the 1930s. They are described in detail in the essay for this website “Antisemitism at the University of Minnesota.” In Minnesota, Republicans, leaders of big business, churches, and right-wing organizations created disturbing alliances. Among the most prominent fascist, pro-Nazi groups were the German American Bund, the Silver Shirts (Silver Legion), and the Christian Nation. Three smaller organizations were headquartered in Minnesota in the mid-1930s, some only briefly. They were the Christian Vigilantes of Minneapolis, the Pro-Christian American Society, and the White Shirts in Virginia, Minnesota. Each combined an anti-Farmer-Labor, anti-union perspective, with Christianity and antisemitism. William Bell Riley, one of Minnesota’s most influential Baptist ministers and leader of the First Baptist Church, as well as a national Fundamentalist leader, moved from championing efforts to stop the teaching of Darwin and evolution in the 1920s to taking up the charge to prove that Jews controlled the world, as envisioned in the vile Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Luke Rader, a self-styled Evangelist at the River-Lake Gospel Tabernacle in Minneapolis, who claimed that Communists “controlled our governor” and were dangers to Christianity, was another prominent figure. Rader subscribed to a great number of conspiracy theories regarding Jewish control of the world and strongly advocated for the need to defeat Jews. It was no surprise, then, that he provided Ray Chase with antisemitic pamphlets.Keillor, Hjalmar Petersen of Minnesota, 153, 154, 163, 298n146.

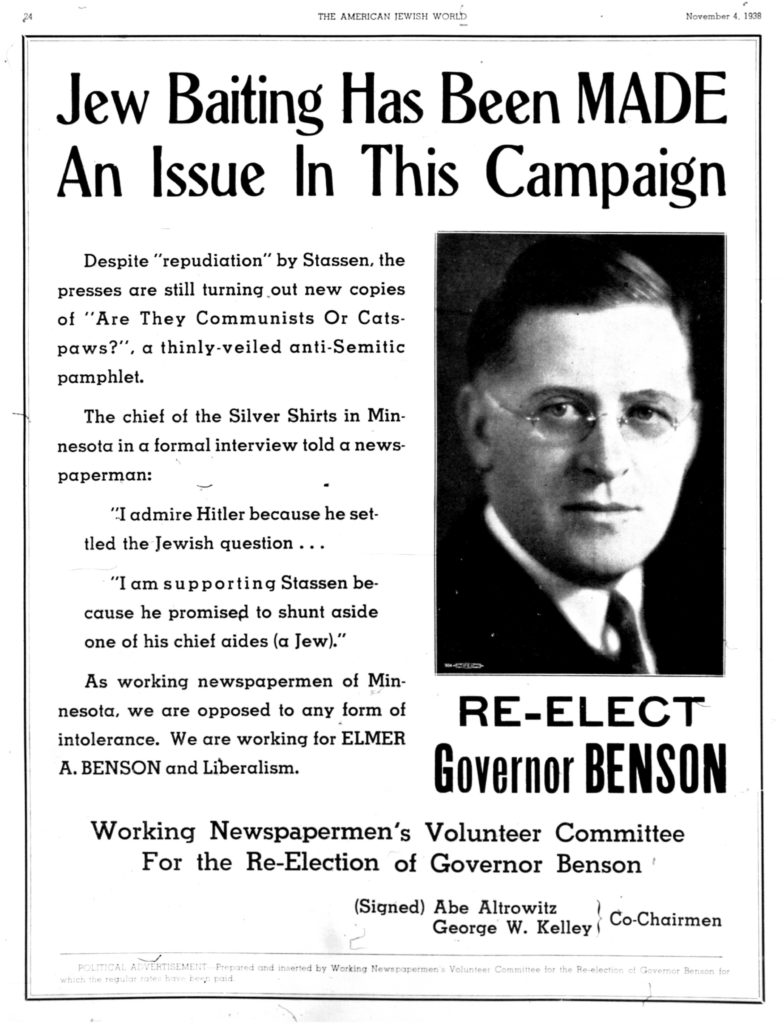

The Silver Shirts, both locally and nationally, took great interest in the Minnesota governor’s race in 1938. Their members distributed leaflets in support of Harold Stassen, and in their newspaper, advised their followers, “If you don’t want Jewish Communism with resulting violence, blood-shed and civil war (and, of course, nobody does) get out at once and help defeat Benson and his criminal cohorts—with Ballots. If it can’t be done with ballots, now, there must be bullets later!” Historian William Millikan notes that in August of 1938, just three months before the election, William Dudley Pelley dispatched one of his top lieutenants, Roy Zachary, from North Carolina to Minnesota to enlist 3,000–5,000 new members. A full discussion of Pelley may be found in the essay for this website “Antisemitism at the University of Minnesota.” He worked with Associated Industries, the organization of major industrial leaders, and worked to infiltrate the Teamster Union Local 544 that had successfully organized a major strike in 1934.Sarah Atwood, “’This List Not Complete’: Minnesota’s Jewish Resistance to the Silver Legion of America, 1936–1940,” Minnesota History 66, no. 8 (Winter 2019): 150; William Millikan, A Union Against Unions: The Minneapolis Citizens Alliance and Its Fight Against Organized Labor, 1903-1947 (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2001), 336-337.

A number of scholars have noted that there were other strong crossovers between the anti-union leaders of big business and the Silver Shirts. George Belden, leader of the Associated Industries, and its predecessor the Citizens Alliance, attended meetings of the Silver Shirts in July of 1938. When Minneapolis Rabbi Albert Gordon wrote to the Associated Industries to inquire what relationship there was between the organization and the Silver Shirts, the organization’s secretary stated the group was opposed to it. Belden defensively replied he was there as an individual and found some good ideas regarding “racketeers,” a code word for union members.Michael Gerald Rapp, “An Historic Overview of Antisemitism in Minnesota, 1920-1960 with Particular Emphasis on Minneapolis and St. Paul,” (PhD dissertation, University of Minnesota, 1977), 73-73. Rapp cites clippings on Belden in the papers of the Jewish Community Relations Council at the Minnesota Historical Society. Additionally, Albert Gordon commented on this campaign in his sociological study of the Jews of Minneapolis in his Jews in Transition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1949), 50-51; Joe Allen, “It Can’t Happen Here: Confronting the Fascist Threat in America in the 1930s” International Socialist Review 385 (September-October 2012), https://isreview.org/issue/85/it-cant-happen-here.Jews and African Americans Respond

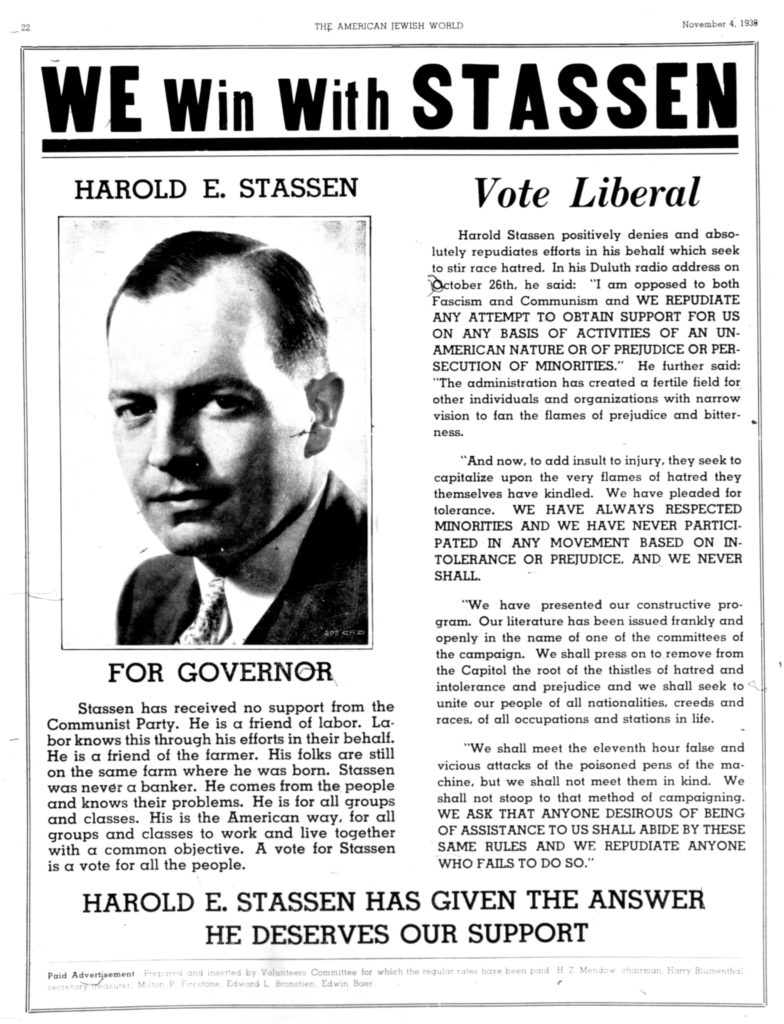

Both Governor Benson and Harold Stassen had Jewish supporters. Nevertheless, Communists or Catspaws was an antisemitic attack that members of the Jewish community, whatever their political party affiliation, refused to ignore, even if some of the Minnesota press did. Minnesota Jews responded in a number of ways. Most significantly, they expanded the newly-created Anti Defamation Council, a defense organization that countered such attacks.

The American Jewish World, which has been continually in publication since its founding in 1912 by Rabbi Samuel Deinard, was the newspaper of the Jewish communities of Minneapolis and St. Paul. It ran two ads shortly before the election. The Farmer-Labor advertisement directly addressed the antisemitism of Communists or Catspaws. The Republican advertisement claimed that Stassen was a “liberal,” and without using the term antisemitism, denounced extremism. Stassen’s Jewish supporters pleaded with him to respond to Chase in some way and this advertisement was one pallid result.

The Minneapolis Spokesman also covered the Chase pamphlet on October 14, 1938. Their front page story titled, “Stassen Blames Race-Baiting Book on State Republican ‘Old Guard.'” covered an exchange between African American activist John Thomas, a graduate of the University of Minnesota and an employee at the Phyllis Wheatley House, and candidate Stassen at what the paper described as the candidate’s first “Negro audience.” Thomas asked him “whether he was in sympathy with an anti-Jewish-Negro race-baiting pamphlet issued by Ray P. Chase, former state auditor. Stassen said he had nothing to do with the pamphlet.” He labeled it the work of “Old Guard Republicans.” Thomas wondered how Stassen would control their activity after the election if “he could not do it during the election.” Stassen’s response was, like the one that he would give to the American Jewish World, that he did not believe in “class intolerance.“Stassen Blames Race-Baiting Book on State Republican Old Guard’,” Minneapolis Spokesman,October 14,1938, https://newspapers.mnhs.org/jsp/PsImageViewer.jsp?doc_id=6ff34a0f-54f7-4bc3-861a-d07acb7dba65%2Fmnhi0031%2F1DFIOV5D%2F38101401

Nicholson worked closely on campus surveillance with a Republican who attacked student activists and circulated racist and antisemitic political propaganda.

Conclusion

In the 1930s, the University of Minnesota was as divided a world as was the State of Minnesota and the Twin Cities. Young men and women contended with the same economic Depression, the same fears about war, and the same limits created by class, sexism, racism, and antisemitism. Many of them were avidly engaged by the same activism and debates about political and economic ideologies that shaped the experience of being American on or off the college campus.

The stakes in these battles were exceptionally high and made even more significant when the progressive Farmer-Labor Party took control of state and national offices in Minnesota. Some student activists supported the party and its commitments to labor and student rights. Many of the University’s administrators did not. Beyond the campus, citizens and elected officials along the political spectrum put the University of Minnesota in the crosshairs of their conflicts with accusations of communism or suppression of student rights.

Political surveillance became a fixture of American life during WWI, with citizens’ ideas, speech, and actions being scrutinized and punished. The 1920s and 1930s was another such era. Labor activists and political radicals were constantly under surveillance by political conservatives and big business in Minnesota and the nation. Accusations of communism became cover for attacks on anyone engaged in efforts to change the lives of workers, people of color, and activists. Extremists on the right built movements around attacks on labor, immigrants, their children, Jews, and the President and his New Deal.

It is in this context that political surveillance at the University of Minnesota, and the quid-pro-quo relationship between Ray P. Chase and Dean of Students Edward E. Nicholson, is best understood. In the name of anticommunism, together, though in different arenas, they not only monitored those with whom they disagreed, but used information that Chase labeled as “facts” to shape the politics of the state, the cities, and the University. Rather than being “factual,” Nicholson and Chase misread the politics of a generation of students, seeing a single point of view rather than the great diversity of left-wing positions. It is particularly telling that three years after Are They Communists of Catspaws was published and discredited, Dean Edward Nicholson provided Ray Chase with names of students and faculty for his notorious files. Ray Chase’s politics and methods were transparent to the Dean of Student Affairs, yet their quid-pro-quo relationship continued unabated.

This unlikely alliance between a man who continuously attacked the University of Minnesota and another who was its Dean of Student Affairs was driven by the extreme anti-union, anti-government, and pro-militarism of the decade. This alliance sometimes found links with Minnesota’s most extremist, racist, and antisemitic elements, as well as the titans of big business, which were driven by conspiracies, secrecy, and surveillance.