Student Movements on Campus and the Struggle for Students’ Rights

With my college generation a new thing developed: “the student movement.” We had a definite effect upon our times. We were in revolt. Not in the manner of many preceding generations…not in the individualistic sense of hating the smugness of middle class life and mores…We believed passionately in the integrity of the human personality, but we sought these ends, not by changing the individual, but by changing the way society—meaning chiefly economic society—was organized. We sought neither wealth nor fame, nor did we expect security and serenity in the end. We had to help change society. We did not feel sorry for ourselves; we felt sorry for the others. The methods would have to be the methods of election and legislation, of large-scale organization, of mass meeting and strike and protest parade.

Eric Sevareid

Not So Wild A DreamEric Sevareid, Not So Wild a Dream (First published 1946; reprint Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1995), 55-56.

The University of Minnesota student movement, like the national one, opposed the United States entering the war looming in Europe and requiring male students to prepare for the military as part of their undergraduate studies. By the mid-1930s, white University student activists also began to address issues of racism that had been important to African American students throughout the decade. Student rights loomed large as well.Robert Cohen, When the Old Left Was Young: Student Radicals and American’s First Mass Student Movement, 1929-1941 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997).

Nowhere did national and state issues meet on the campus more forcefully than in the requirement that male students participate in military drills to prepare the nation for war. Farmer-Labor Governor Floyd B. Olson made opposition to required drills at the University of Minnesota part of his anti-war stance as he ran for re-election. In his second term as governor, he nominated eight new regents in 1935, and several of them voted against requiring male students to enroll in mandatory ROTC, which ended the practice.

Strike for Peace

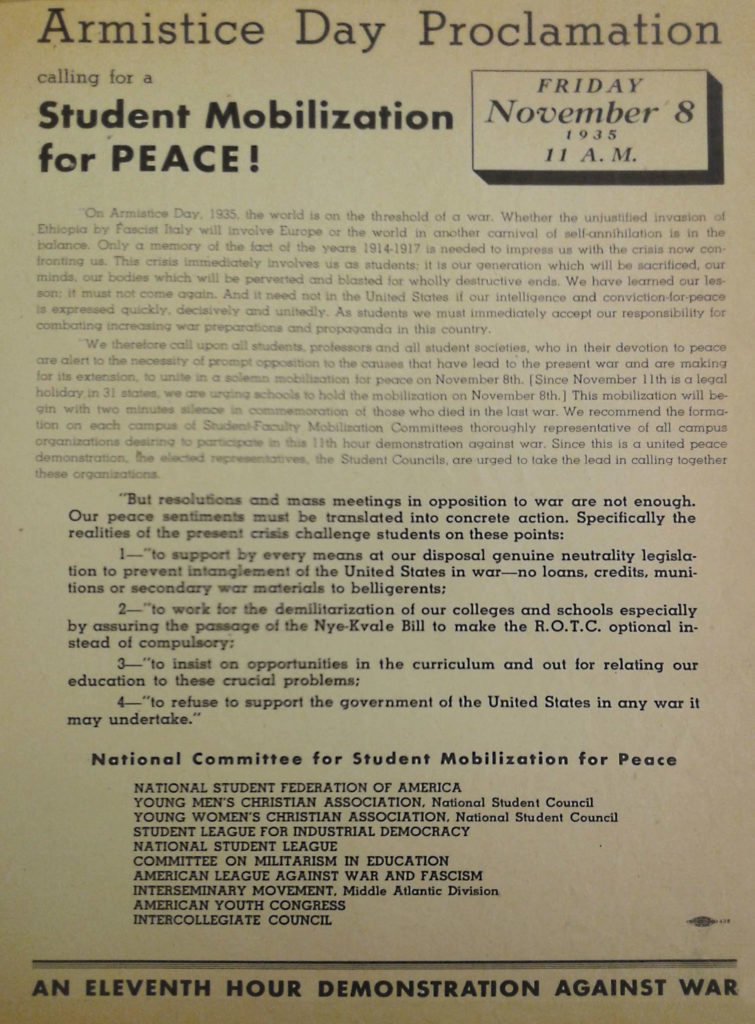

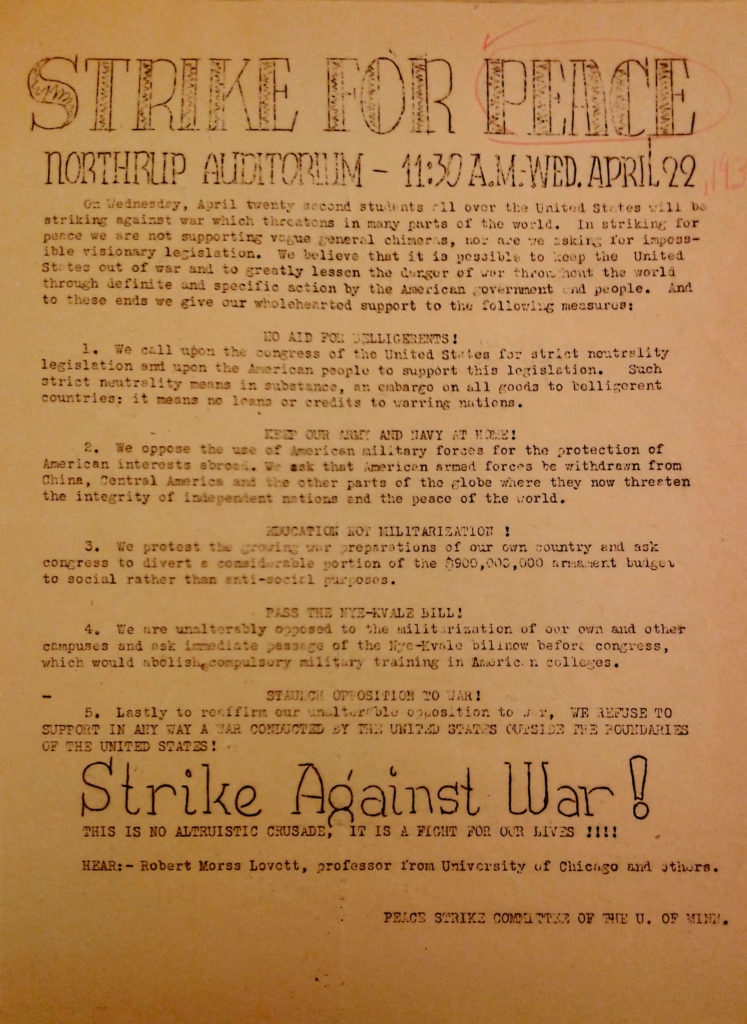

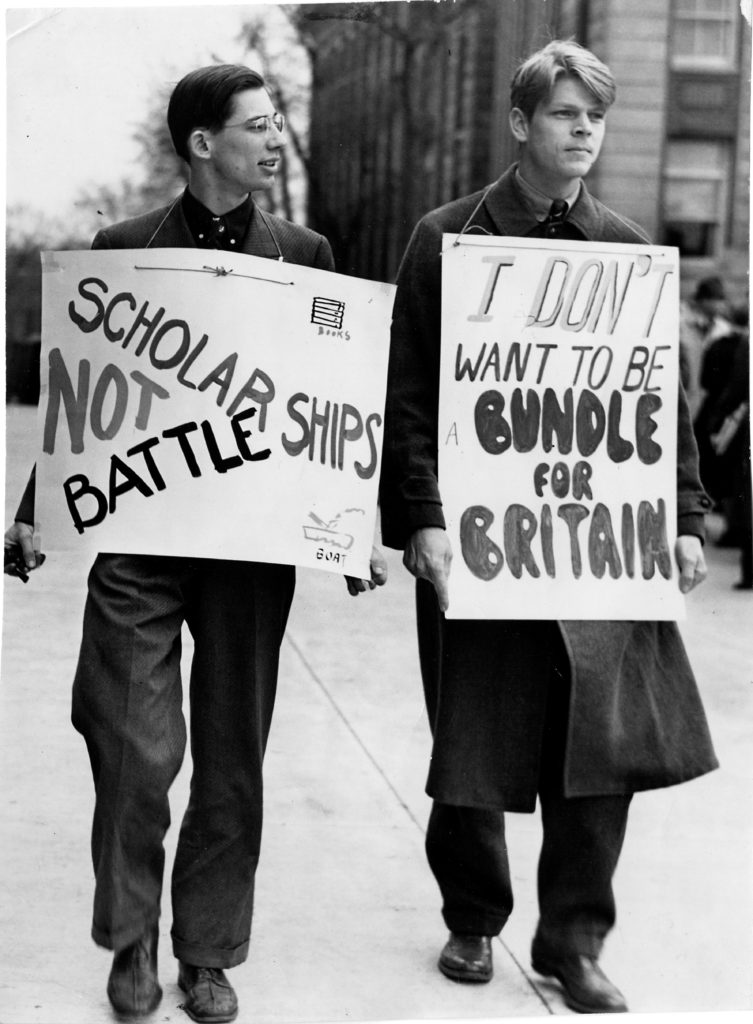

The American student movement, which focused on international issues even more than domestic ones initially, opposed the United States entering another war. Beginning in 1934, activists mobilized students across the country to participate in “Peace Strikes” in April and November, marking the beginning and end of World War I. Students boycotted classes at 11:30 a.m. for one hour and held the largest campus demonstrations to that point in American history. The strikes continued until 1941 when the United States declared war after the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor.

In 1935, for example, 3,000 Minnesota students assembled in the plaza and on the steps in front of Northrop Auditorium for one of the nation’s largest anti-war demonstrations. Fliers were used both to advertise the events and to lay out the positions of the organizers locally and nationally. President Coffman would not allow students to enter the auditorium because he disagreed with their call to miss classes. The demonstration attracted hecklers and pro-war students, and while they made some efforts to disrupt the pro-peace activists, they were not effective in stopping the peace strike.

A few student testimonies from the period reflect on these events. What undergraduate Rosalind Matusow, an activist in the mid-1930s, recalled about the demonstration was Governor Floyd Olson’s speech. She was also impressed by the diversity of opinions among students.

I immediately became involved in student activity, anti-war activity, you know that was the big worry then of all of the students, war and fascism. I remember the first student peace strike. We thought it was just huge because the whole plaza in front of Northrop Auditorium was just filled with students.

There was a tremendous amount of work and activity on all kinds of levels. A very few people started it and you know it really developed into a tremendous movement.

There were all kinds of divergent opinions and I got quite a real political education, during that time. I hadn’t been exposed to people having different shades of opinions and you know, it was a good education.

Rosalind Matusow Belmont

Minnesota Historical Society, Oral History ProjectOral history interview with Rosalind Matusow Belmont, April 4, 1982, 20th Century Radicalism In Minnesota Oral History Project, Minnesota Historical Society, http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/oh30.xml.

From the beginning, the Peace Strikes were organized by several different campus groups. They included the YMCA and the YWCA, the Social Problems Club, as well as the All-University Council (which was the name for student government). The campus chapter of the National Student League was also an ally, as well as, for a time, the more moderate Practical Pacifists.

Campus activists Lester Breslow and Richard Scammon attributed the success of their activism to left-wing political pluralism rather than orthodoxy that had not previously succeeded. They described the “elements” of their coalition as “liberals, radicals, Communists, Farmer-Laborites and Socialists,” which all joined the newly formed national organization the Social Problems Club where “so far no single group has tried to push its program down the others’ throat, so no internal struggles for control have developed.”

Why Did Students Oppose a War Against Fascism?

If World War II is remembered as a “good war” because it defeated Nazism and fascism, then why did the vast majority of Americans across the political spectrum oppose entering a second world war during much of the 1930s, and why students in particular?

World War I ended in 1918 and left over 17 million dead; 11 million soldiers perished. Students faced the possibility of war again, barely a decade later. A brief oath, known as the Oxford Pledge, was advanced in 1933 by Oxford University’s debating society in England. It stated, “This House will in no circumstances fight for its King and Country.” The same semester, American students adapted the pledge to state, “I will not support the government of the United States in any war that it might conduct.” Tens of thousands of students took this oath on both sides of the Atlantic. In 1933, anti-war activists at the University of Minnesota held a debate on the Oxford Oath at the University recreation building attended by 300 students. Nearly every male student who attended rose to take the Oxford Oath. Fifty ROTC cadet officers walked out in protest.

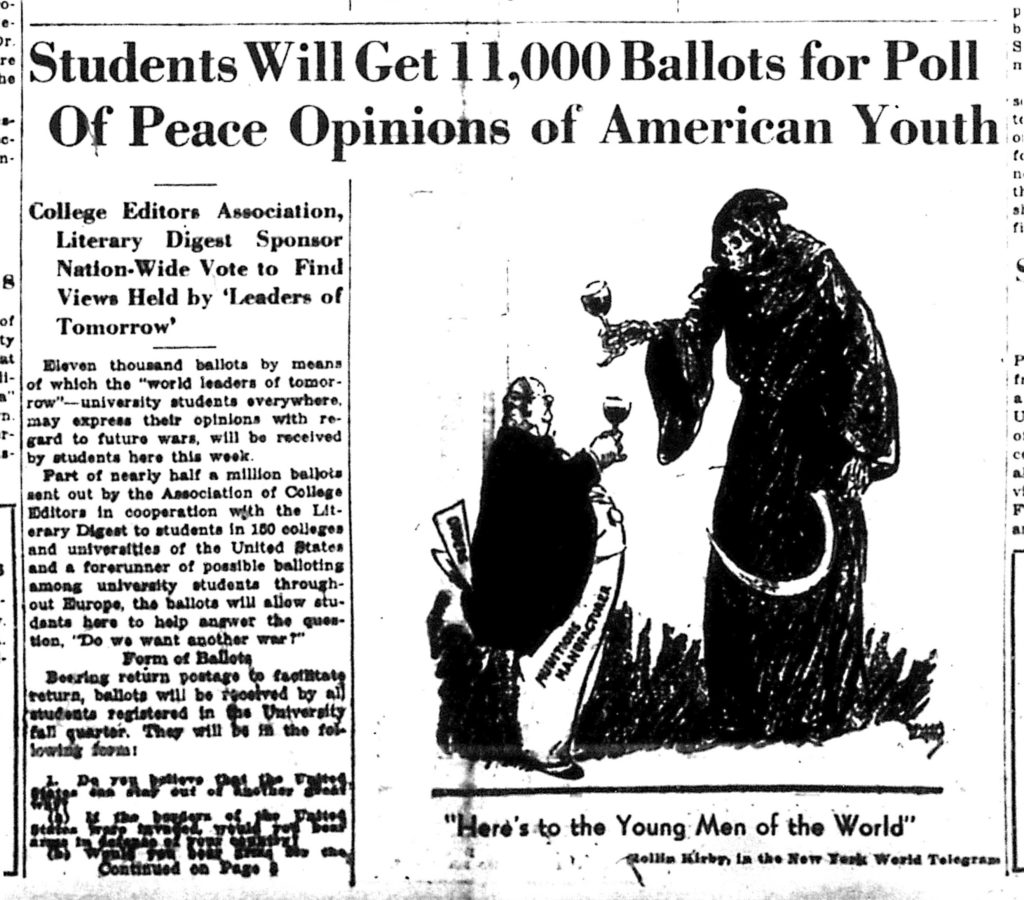

In 1935, The Literary Digest, a popular weekly that canvassed opinions on a variety of political topics, sought student views on war. Questions included whether students were willing to fight a war outside the United States or within the nation’s borders and whether industries should profit from building arms. More than 4,000 University of Minnesota students cast ballots and nearly 90 percent declared that they would not take up arms outside the borders of the United States. Minnesota students were in the mainstream of American student opinions.

These strong anti-war sentiments among students in the United States had several sources. Activists often used the term “lessons learned” from World War I as the foundation of their support for neutrality and their refusal to die in another war. These were the “lessons”:

- President Woodrow Wilson had promised that World War I would make the world “safe for democracy.” That promise failed, and Europe was now increasingly dominated by dictators and fascism. Activists argued that war could not solve problems.

- Student activists argued that profits and greed caused World War I. The United States responded to the demands of bankers and the munitions industry and the war made them rich. Students argued that economic gain was the only reason nations went to war, and they rejected nationalism and militarism.

- Germans were accused of some atrocities during World War I that were ultimately revealed to be fabricated. The war had, in the face of this propaganda, created an atmosphere in the United States of anti-German hysteria that led to the suppression of American civil liberties. Student activists held their families and government morally responsible for this harsh chapter in the nation’s recent history.

The Administration Attempted to Contain and Control the Peace Strikes

President Coffman and Dean Nicholson actively worked to undermine the rights of students to assemble, discuss, and debate the war. Coffman would not allow students to enter Northrop Auditorium to assemble for their demonstrations, which is why they were held on the plaza. Governor Olson addressed activists on the steps of the building, below the president’s office window. Governor Olson told the students assembled on the plaza, “No government has the right to compel its citizens to bear arms in a war of aggression. The history of most wars shows that they were fought for material reasons and not for human rights and for human ideals.”John S. McGrath and James J. Delmont, Floyd B. Olson: Minnesota’s Greatest Liberal Governor (Self-published, 1937).

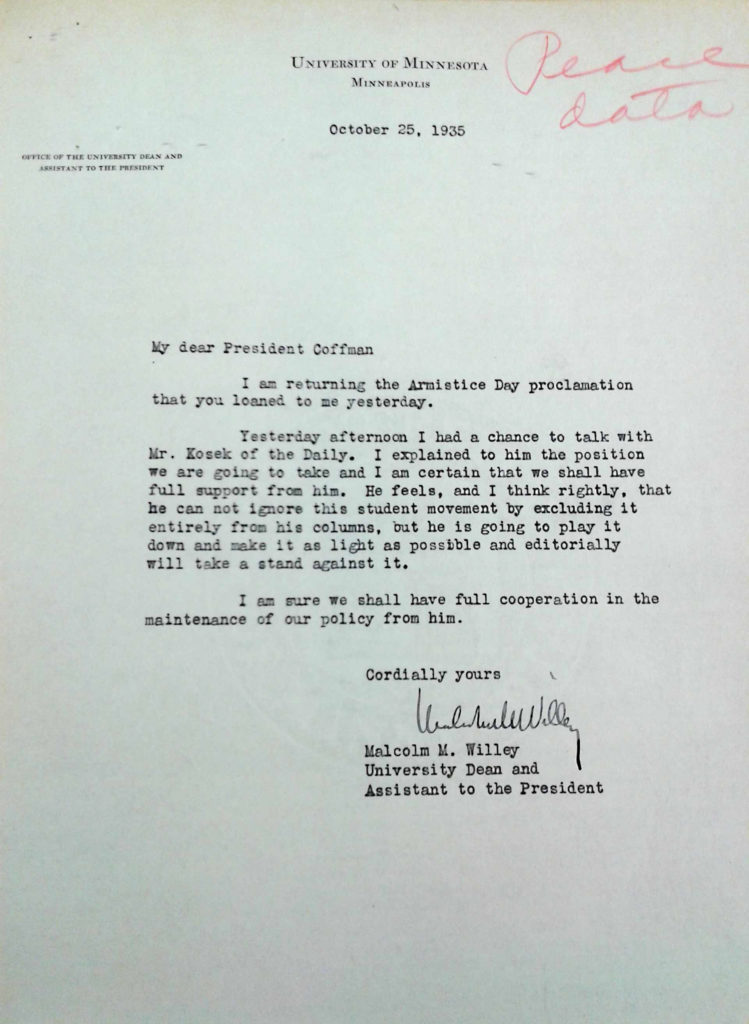

Coffman’s assistant, Dean Malcolm Willey, triumphantly informed him that he was able to minimize the 1935 Minnesota Daily’s coverage of anti-war events by speaking to the editor.

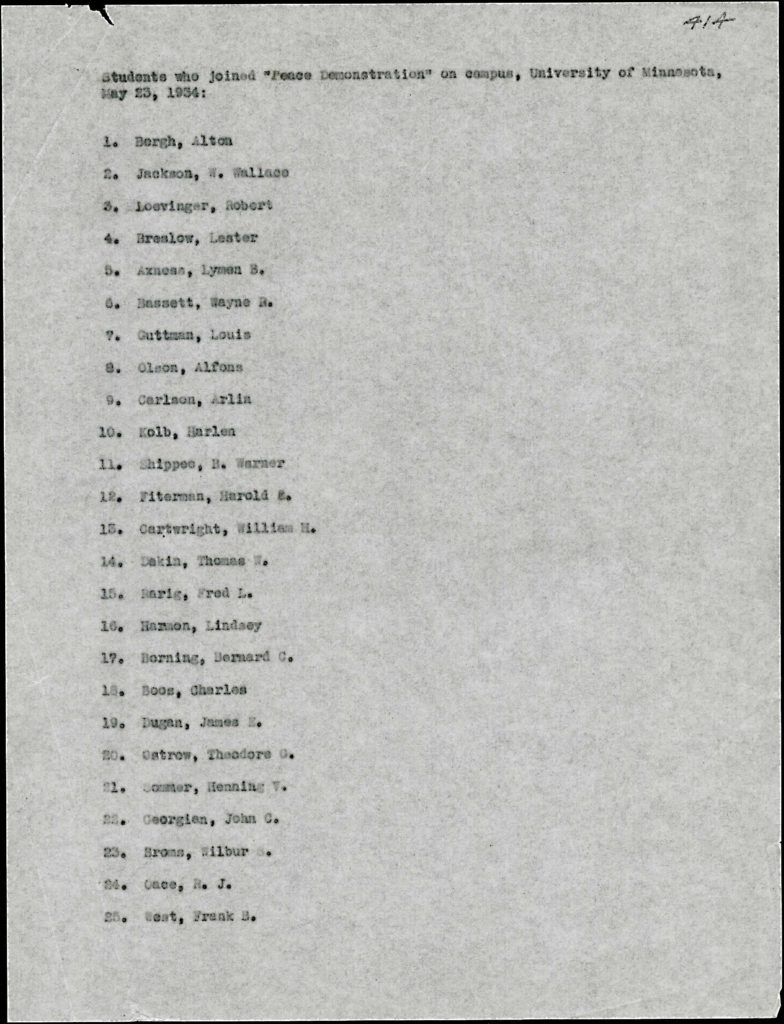

Political surveillance involved monitoring students at demonstrations, among other activities. People in Dean Nicholson’s office may have collected names of demonstrators to be passed to Ray Chase, a Republican operative, to build his files of “subversive” students. Another source may have been people working for Colonel Potts, both discussed in the essay “Political Surveillance of the University”.

The Fight to End Required Military Drills

There seemed to be a law hanging over from Civil War days which made it necessary for any boy striving for education at the people’s university to don a hand-me-down uniform and shoulder a 1905 unfireable Springfield rifle three times a week for a full two years. [It was] a harsh interference with our liberty and a humiliating affront to our personal dignity.

Eric Sevareid

Not So Wild A DreamEric Sevareid, Not So Wild a Dream (First published 1946; reprint Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1995), 59.

Public universities required undergraduate male students to participate in military drills and classes in some periods of the 19th and 20th centuries. Under the Morrill Act of 1862 that established public universities through the sale of federal lands, male students were obligated to study “military arts” along with agriculture, science, and mechanic arts. The University of Minnesota instituted that requirement under the ROTC (Reserve Officer Training Corps) at its founding in 1869 and required young men to prepare for defense of the nation and war.

Following World War I, however, students began to question the necessity of required drills and particularly the place of militarism on American campuses. At the University of Minnesota, student activists built a powerful movement to end required drills which stretched back to the mid-1920s. The students’ complaints varied. Some declared themselves “conscientious objectors” who were opposed on principle to all wars. Some decried the waste of their time due to the terrible quality and disorganization of the classes. Some objected who were part of the anti-war movement and opposed militarization of the campus and the nation.

At the same time, other student groups supported the drills on the grounds that the United States needed to be prepared in case of attack. They called themselves the “Practical Pacifist Club.”

The Anti-Compulsory Drill Debate

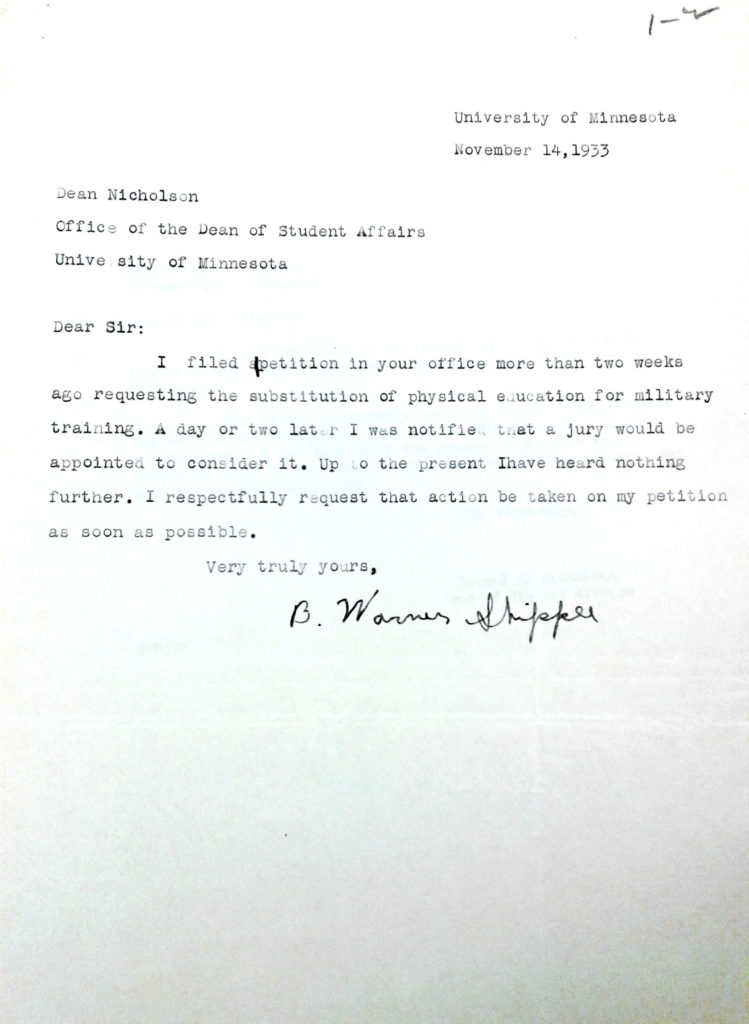

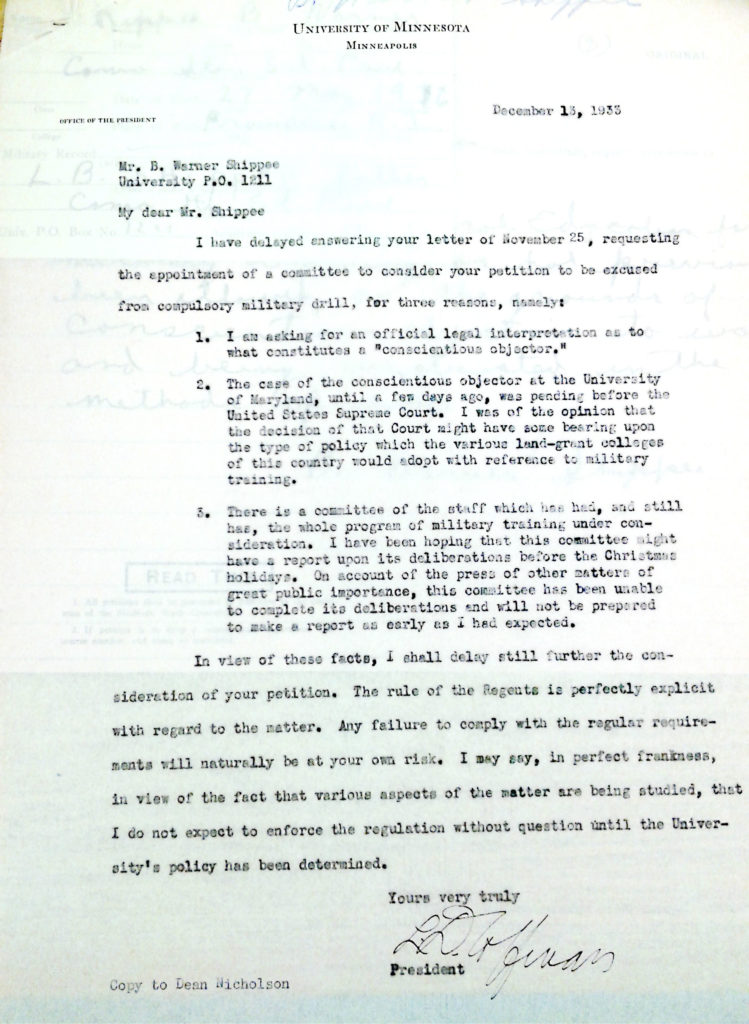

A new group at the University of Minnesota launched an effective campaign to oppose compulsory drills. These students called themselves the Jacobin Club, and they shared a number of powerful principles, chief among them opposition to war and to required ROTC drills and classes. The Jacobins were a unique fraternity for the 1930s. Their “house” was the student union, and they included Jews and non-Jews at a time when no social fraternity was integrated by religion; however, the Jacobin membership included no African-American students. The Jacobins ranked highest in grade point averages of all fraternities and dominated student government, leadership of the Minnesota Daily, and anti-war activism. Many of them ended up on every list created by Ray Chase of “Radical Students” to be watched, which is discussed in the essay on this website “Political Surveillance of the University.” The Jacobins constantly challenged Dean Edward Nicholson, who did everything in his power to control and suppress their effective activism.The Jacobins were the subject of a 1959 article by Terry Fisher in the University of Minnesota publication, The Ivory Tower (November 16, 1959), 5, 10-12. Terry Fisher described the group and its struggle to end ROTC on campus from 1933 to 1935. This article was included in the papers of Warner Shippee, Courtesy of Elizabeth Shippee. For an account of the Jacobins and their activism on campus see Eric Sevareid, Not So Wild a Dream (First published 1946; reprint Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1995), 60-67. These publications both note Dean Edward Nicholson’s deep hostility to the Jacobins.

The Jacobins were aided in their efforts to stop required drills by an incident in 1934. Sheldon Kaplan, an undergraduate, was suspended from the University because he skipped two days of drill class. His case became a cause for activists. His suspension was featured in the Minnesota Daily whose editorial leaders opposed required drills. His outstanding grades were splashed on the newspaper’s front page along with the F on his report card in the military course. The article quoted Kaplan’s comment that he was told by the officers in charge that he was “free to sleep through the classes.”

Kaplan was defended by a Jacobin student activist, Richard Scammon, before the ROTC “military tribunal,” which called for Kaplan’s suspension. President Coffman overrode the tribunal’s decision and Kaplan returned to class. The fight gained momentum.

On May 23, 1934, the activists scheduled a demonstration against compulsory drilling the same day that the annual spring ROTC review took place. Dean Nicholson attempted to stop the student demonstration, which was written about in the Minnesota Daily. When the students refused to cancel their demonstration, the Dean simply censored the newspaper and would not allow it to publish any more information about the protest. He lifted the censorship after two days. ROTC had never objected.

The anti-ROTC protest was a triumph for the coalitions of student groups that organized it. Lester Breslow and Richard Scammon reported that on the day of the demonstration volunteers distributed 6,000 handbills at every entrance and street car stop on the campus. One volunteer was attacked, but a monitor pulled the attacker off his victim. Later, 1,500 people gathered outside of the Minnesota Union (subsequently called Coffman Memorial Union) to hear from speakers through the window of a room. Students from “all campus elements” addressed the crowd. Not only men, but women also passionately spoke out about this issue: a woman from Mortar Board, the Senior Women’s Honor Society, and another from the women’s debate team criticized war and armaments manufacturers. Students from the Farmer-Labor Club and the National Student League as well as the first recognized conscientious objector on the campus Ray Ohlson also called for the end of required ROTC. On another part of the campus the ROTC cadets held their annual parade. The future of ROTC rested with the Board of Regents.Lester Breslow and Robert (also known as Richard) Scammon, “One Front in Minnesota,” Student Review (November 1, 2015): 14-15.

Debate About War and the Wide Reach of “Campus” Politics

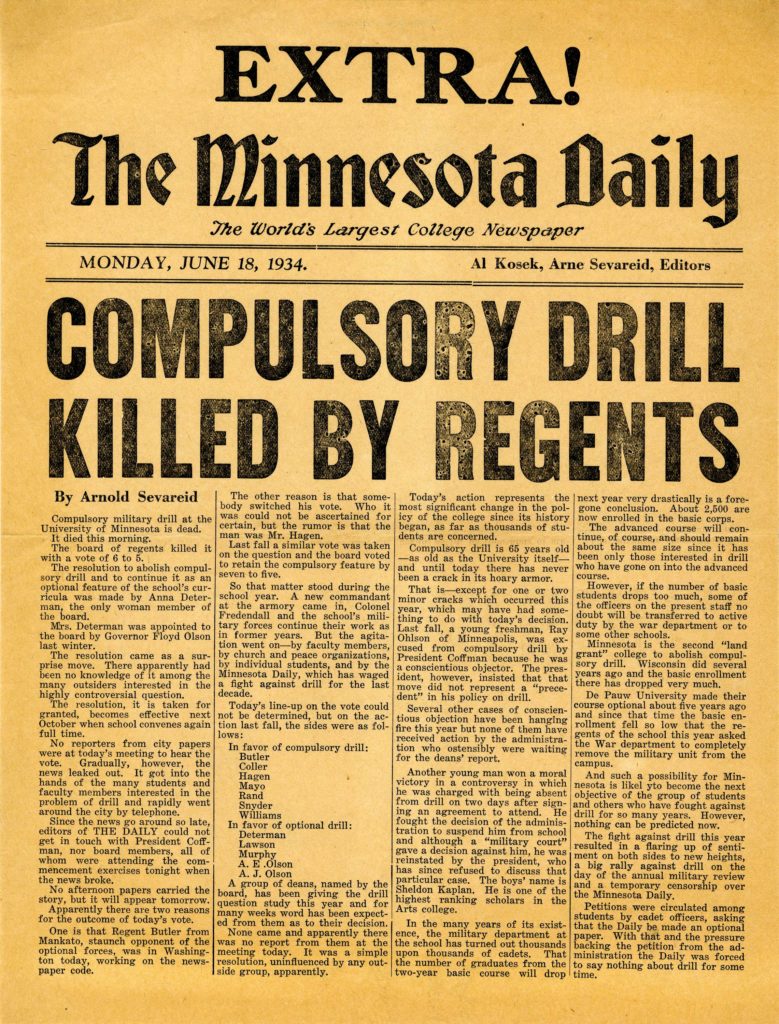

The decision to end mandatory drills rested with the Board of Regents. Despite mounting opposition to the drills from students and the Farmer-Labor Party, the Regents voted early in 1934 to maintain the requirement. However, at their June 18, 1934 meeting, the Regents reversed course and voted 6 to 5 to end the requirement and made drills voluntary. Though the issue persisted through 1935, mandatory drills never returned to campus.

The popular Farmer-Labor Governor Floyd Olson had nominated the candidates for the eight open regent positions earlier that year. Governor Olson shared the Progressives’ anti-militarism stance and Minnesota Republicans feared that Olson’s choices would tip the balance against drills. State and campus politics were shaping one another. The minutes of the Board of Regents’ meeting recorded the vote and took the unusual step of including how each regent voted. On the question “Shall the rule requiring compulsory military training at the University be repealed and military training be made optional, effective beginning with the academic year 1934(–1935)” the Regents voted as follows:A discussion of Governor Olson’s appointment of regents and his commitment to end required drills may be found in Arthur Naftalin, A History of the Farmer-Labor Party in Minnesota (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Minnesota, 1948), 266-268.

1. Coller: No

2. Determan: Yes

3. Hagen: No

4. Lawson: Yes

5. Mayo: No

6. Murphy: Yes

7. Olson, A. E.: Yes

8. Olson, A. J.: Yes

9. Rand: Yes

10. Snyder: No

11. Williams: No

Military training was therefore made optional, effective beginning with the academic year 1934–35.Board of Regents’ Meeting Minutes, June 11, 1934, University of Minnesota Board of Regents, University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy, https://hdl.handle.net/11299/45451.

Student journalists put out a special edition of the Minnesota Daily for graduation and the next year devoted a page of the Gopher yearbook to their victory.

A Question that Haunted the Student Movement

The vast majority of the male students who opposed entering the war eventually supported it and fought in it after the United States declared war following the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Did the “lessons learned” from World War I apply to World War II? Why were anti-war activists slow to understand the dangers of fascism and the genocidal program of Adolph Hitler and National Socialism?

Looking back on this period, former anti-war activist and journalist Eric Sevareid wrote in his memoir:

The actions of Hitler were being justified on all sides by a lot of people who believed in capitalism, in preparedness, in all the conventional ideas, as merely a necessary attempt to bring “order” into German life, and to give the Germans, frustrated by the mistaken terms of the Versailles Treaty, a sense of dignity and place in the world. These people were inclined to approve the Nazis as a “stabilizing” force. But we who had learned from history…knew the moment the Nazis burned books [in 1933] that Fascism wanted war. Why did we not immediately go all out for preparedness [for war]? We grasped the implications of Fascism, but we failed to grasp the scale of the thing, to understand a world conspiracy that was under way.

Eric Sevareid

Not So Wild A DreamEric Sevareid, Not So Wild a Dream, (First published 1946; reprint Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1995), 64.

Student Rights in the Student Movement

American student activists readily grasped that their struggle against war was inseparable from their need for students’ rights on campus. In 1935, they passed a resolution that called for freedom of speech, assembly, and the press. From 1934-1936 student leaders waged a campaign for reform in order to give students more control over their own activities and a stronger voice at the University. However, in 1936, the University of Minnesota’s administration and Regents passed multiple rules to further limit or withdraw all students’ rights and rejected the vote of the student body to reform their governance system despite it exceeding the required 75 percent. The student activists’ call for student rights in the 1930s echoed through the student movements of the 1960s and beyond.

The Right to Form Political Groups Freely

Students sought the required official recognition for their clubs, leagues, discussion groups, and organizations in order for them to meet on the campus. During the economic crisis of the Great Depression, shared meeting spaces were crucial to a community life. The landscape was dynamic: activists formed organizations, dissolved them to join forces with others, and branched off as well. Visions, ideologies, activism, and leadership changed in these left-wing groups–they were anything but monolithic.Robert Cohen, When the Old Left Was Young: Student Radicals and America’s First Mass Student Movement, 1929-1941 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997).

Dean Nicholson had absolute authority over whether students could form these groups through his leadership of the University Senate Committee on Student Affairs. President Lotus Coffman appointed the student members of the committee and faculty members, according to the committee minutes, seemed always to agree with the dean.

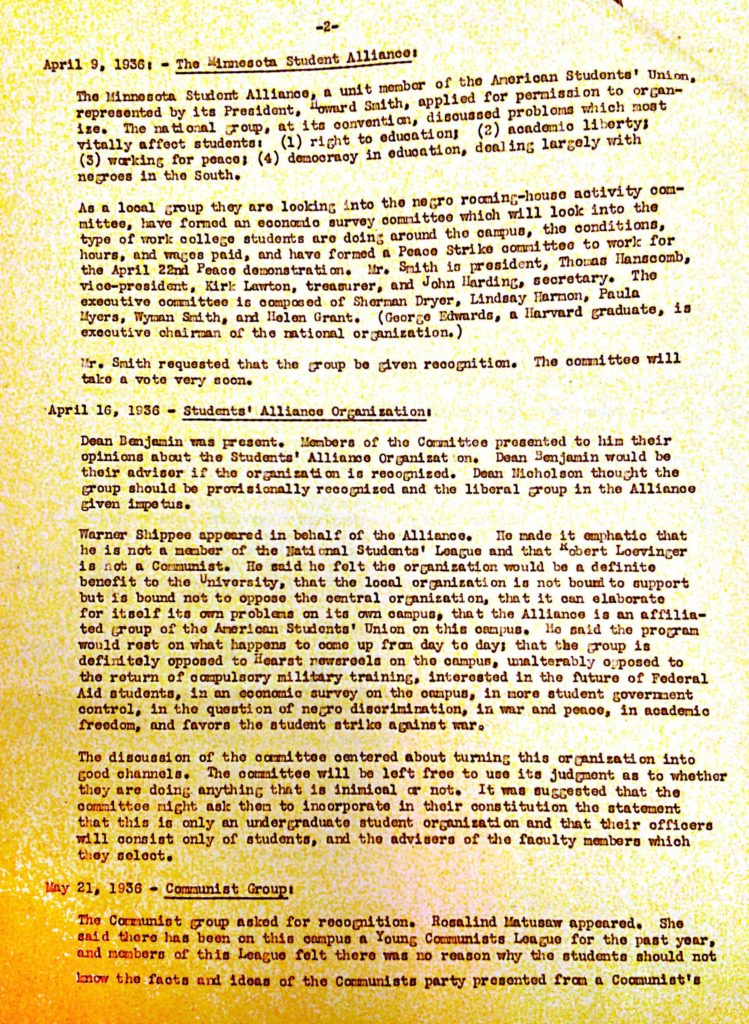

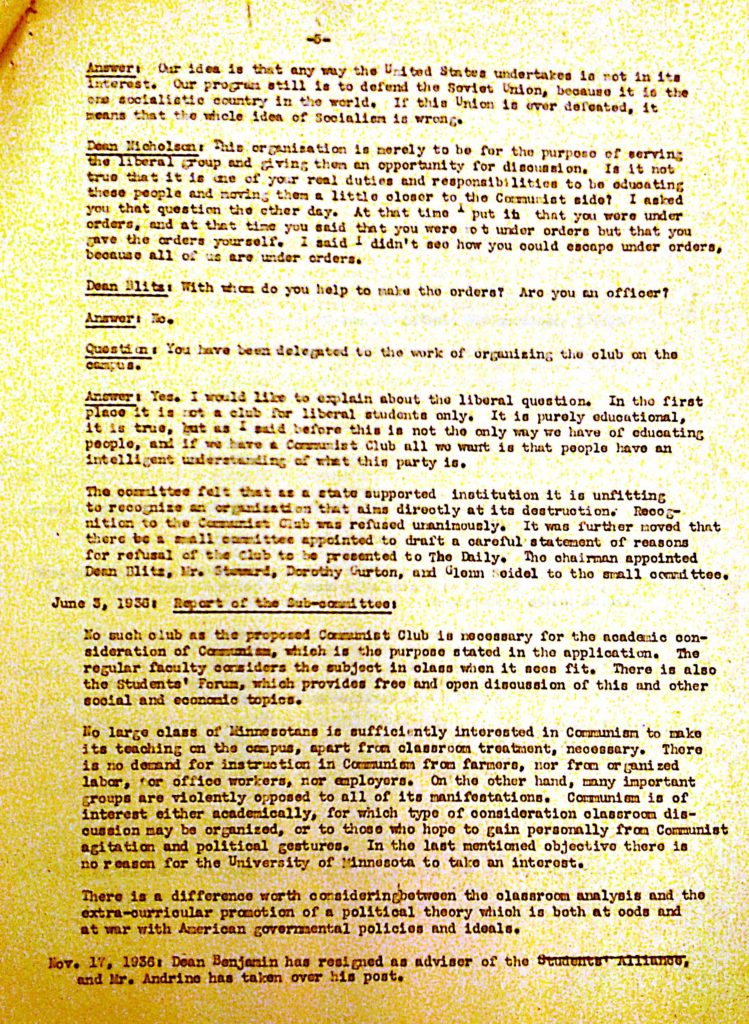

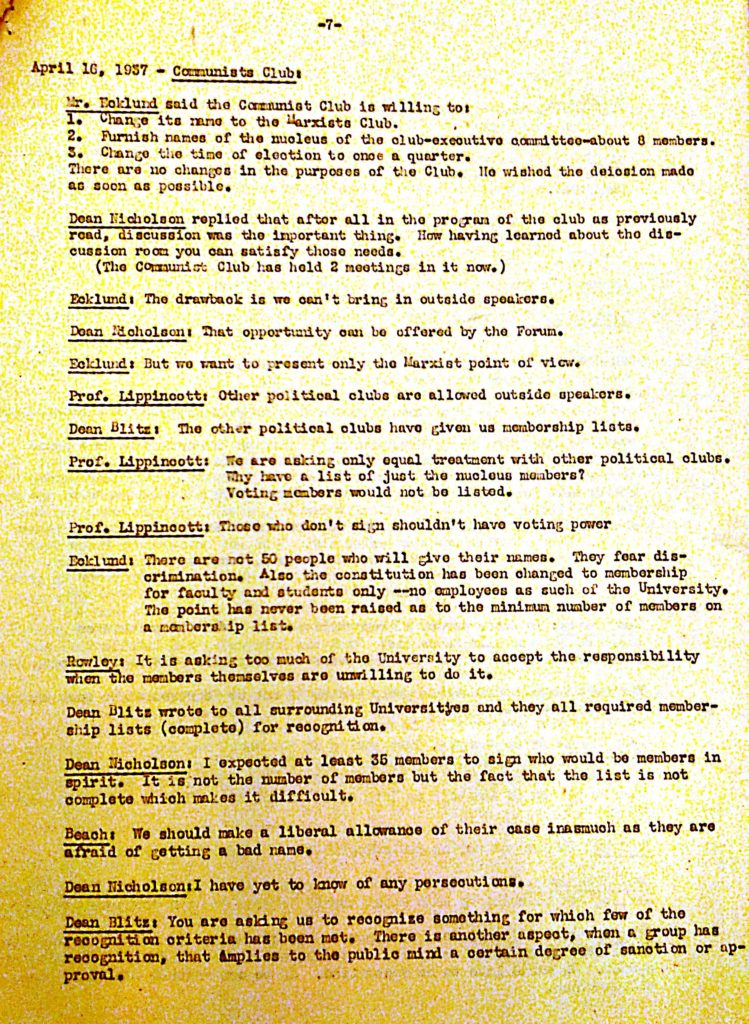

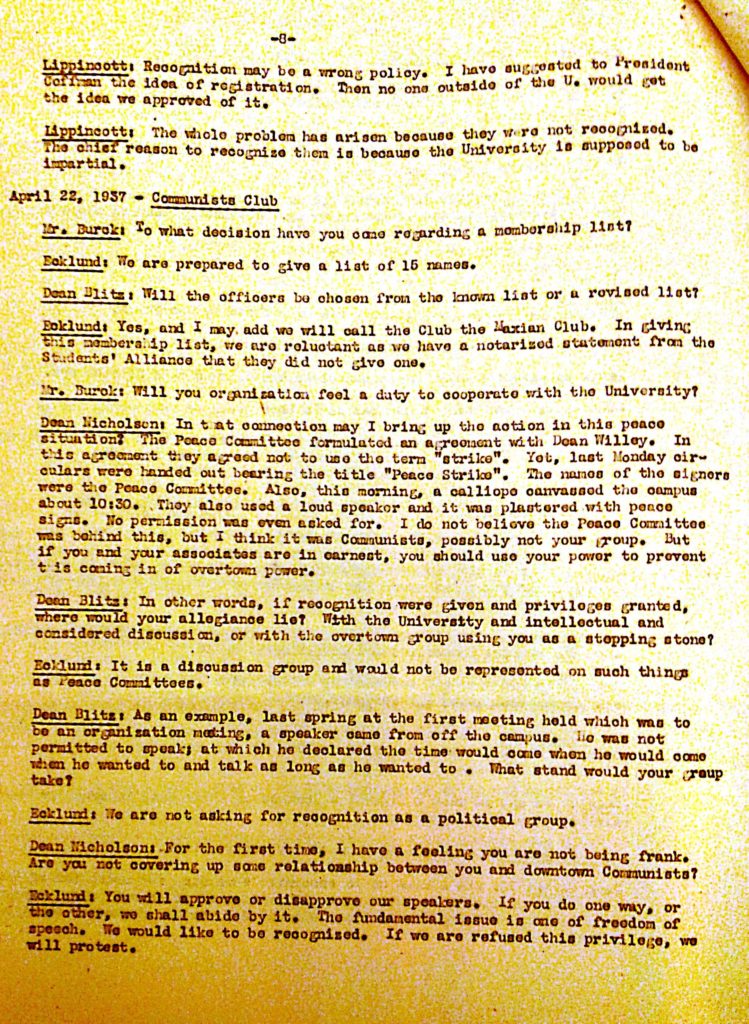

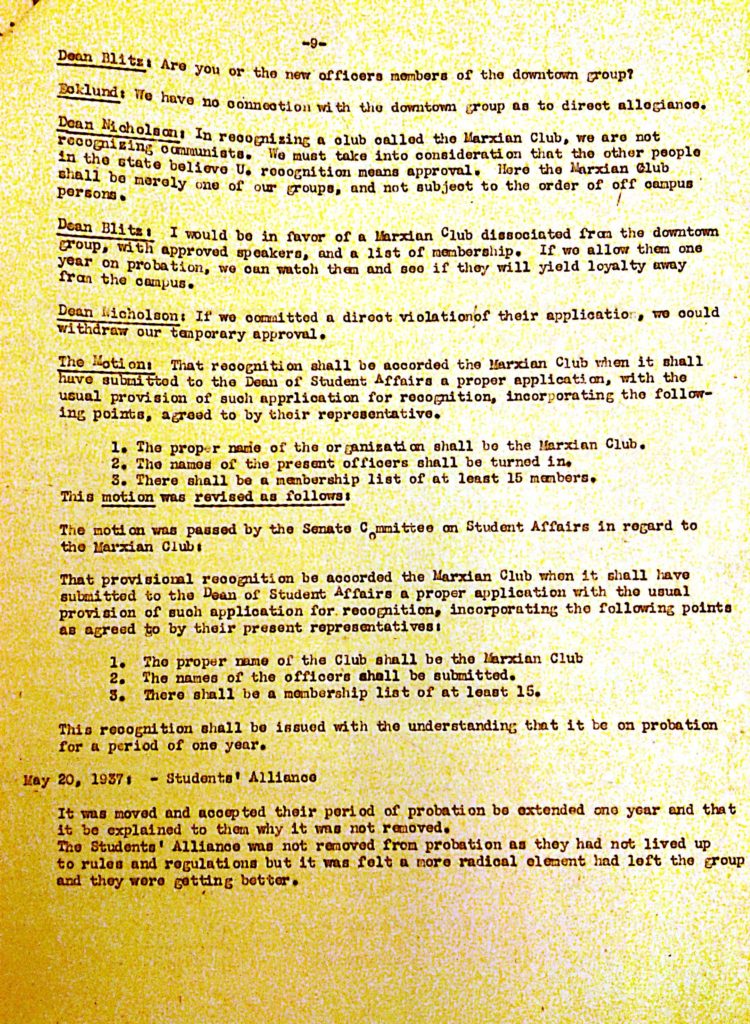

An “abstract” of the minutes of meetings of the University Senate Committee on Student Affairs in 1935 and 1936, in addition to other comments, offers a front-row seat to the court-like proceedings students and faculty endured in their quest to form an organization. In addition to listing the names of students and faculty who appeared before the committee the summaries of dated meetings reveal that Dean Nicholson, and to a lesser extent Dean of Women Anne Blitz, peppered with questions the students and faculty advisors who petitioned to form groups. The advisors were distinguished faculty of the University of Minnesota, including Benjamin Lippincott (Political Science) and Harold Benjamin, Assistant Dean of the School of Education. Nicholson rejected the formation of a group if he believed it “was under the control of the Communist Party.” He refused many proposed clubs where students wanted to discuss political issues or hear from a wide variety of speakers who would be invited to campus. He insisted to the students and faculty advisors that such groups were unnecessary and undesirable. Among those groups students sought to form was the Social Problems Club, the National Student League, the Communist Club, Minnesota Student Alliance Organization (chapter of American Students’ Union).

In 1936, for example, Warner Shippee was required to attest that he was not a member of one organization presumed to be communist in order to receive recognition for another group. He had to defend Robert Loevinger, another student active in student government and antiwar activism, as “not a communist.” Among the concerns of the new group, an alliance of several progressive groups, were “federal aid to students, Negro discrimination, and academic freedom,” and others. Nicholson thought the group might be approved “provisionally,” but only if he could dictate which groups would be in the alliance and which he could exclude.Abstract of Committee on Student Affairs Meeting Minutes, October 1-24, 1936, Ray P. Chase, Minnesota Historical Society, Box 42, Folder October 1-24, 1936, pp. 2-4. This document also covers the work being done by the National Student Alliance and the quizzing of Rosalind Matusow.

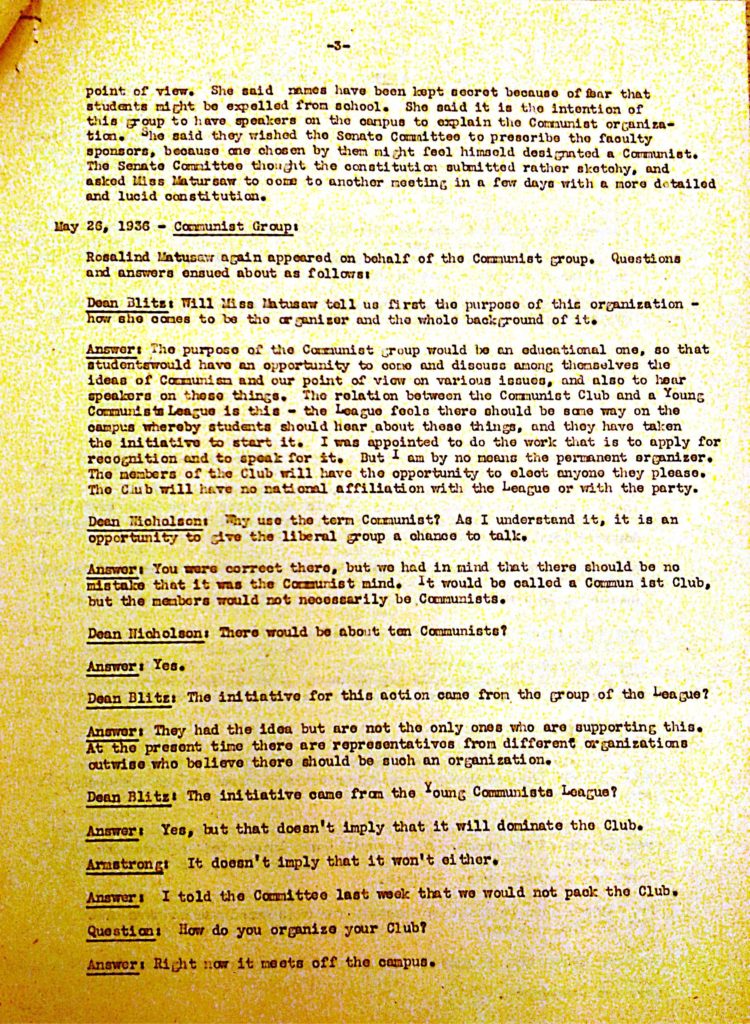

Pages that were summarized and abstracted from the meeting minutes focused not only on the refusal to recognize a communist club, but on querying the student who proposed it. Nicholson asked Rosalind Matusaw about how she spent her time, what she was doing at the women’s dormitory Sanford Hall, and to whom she was speaking when she was there. She did ask the committee members why that was relevant. There were also debates over students providing Dean Nicholson with lists of members of their groups. Activists stated plainly that they were afraid these lists could be given to organizations outside of the University of Minnesota. That is precisely what happened. The names of students, and one faculty member, interviewed at these meetings appeared on lists of “radicals” created by Ray Chase with information from Dean Nicholson. Chase shared these lists with other groups and right-wing activists to “prove” communist infiltration of the University of Minnesota, which is discussed in the essay for this website “Political Surveillance of the University.” At no point in the meeting did Deans Nicholson and Blitz promise or affirm that the names would never be revealed.The faculty members of the University Senate Committee on Student Affairs were Elvin Stakman, Department of Plant Pathology; Lloyd M. Short, Political Science; and E.E. Hartly, Electrical Engineering. Senate Committee on Student Affairs Minutes, 1936-1937; 1942-3, Box 80, University of Minnesota Archive.

Communist and Marxist clubs were often among the most controversial organizations proposed by students at the University of Minnesota. Organizers wanted the opportunity to read Karl Marx and other economic thinkers. Students required faculty sponsors and had to provide a list of their club members.

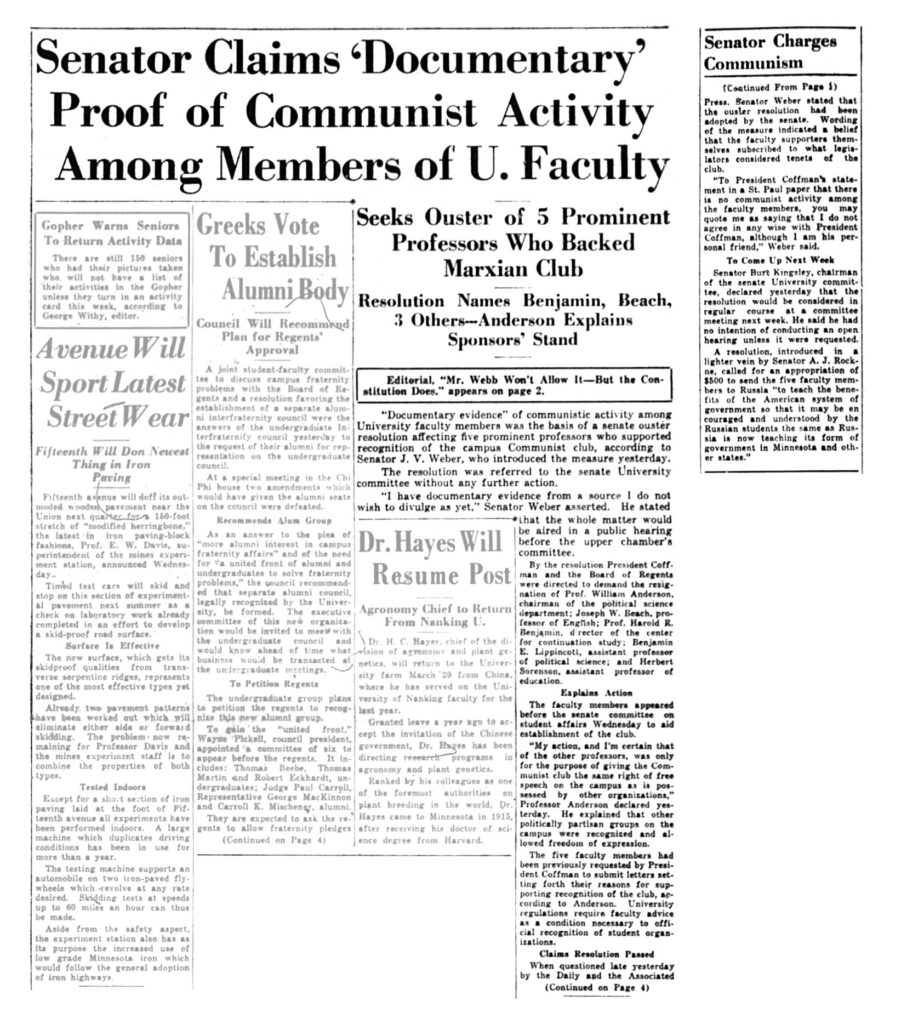

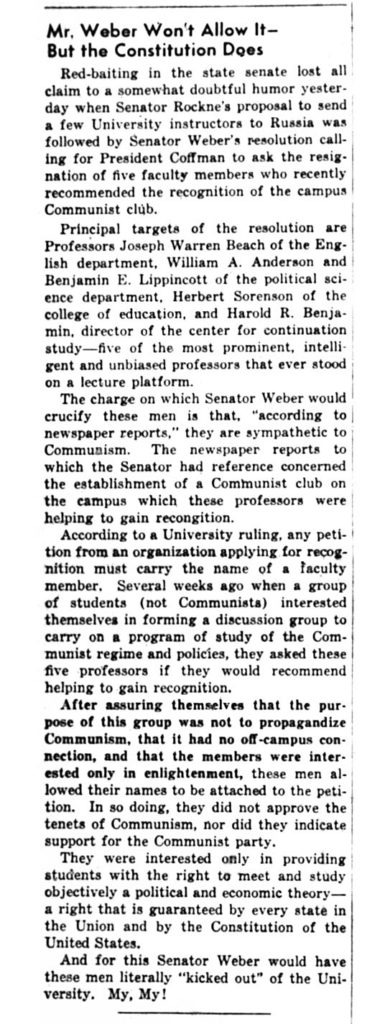

Five well-known faculty members agreed to sponsor the Marxist Club because of their commitment to the principles of students’ rights to free speech and the importance of the open exchange of ideas in society and on campus. They included Harold Benjamin, Center for Constitutional Study; Benjamin Lippincott, Political Science; William Anderson, Political Science; Joseph Beecher Ward, English; and Herbert Sorenson, Education. State Senator J. V. Weber immediately sought to have all of them fired and “sent to Russia” because he labeled them Communists.

The Minnesota Daily editorialized strongly against the Senator’s tactics, and referred to the faculty sponsors as “unbiased.”

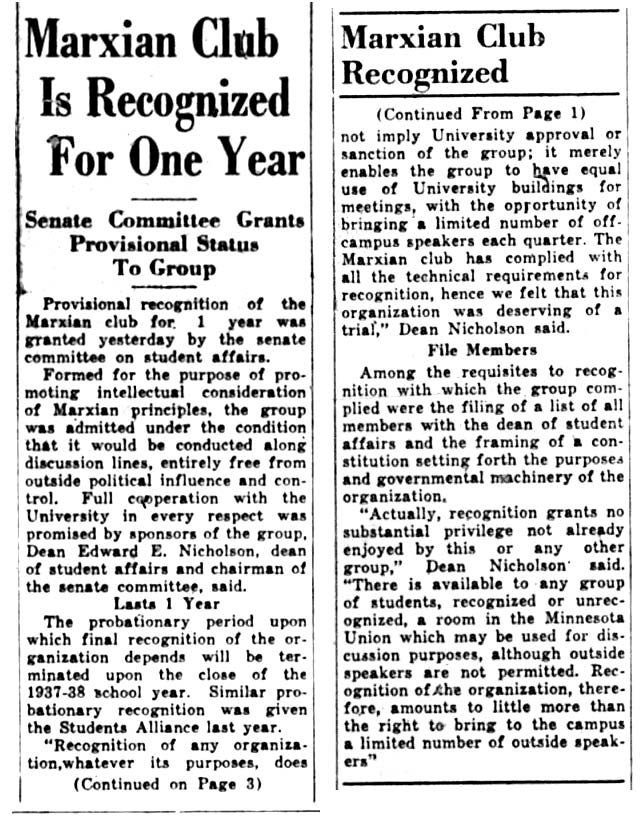

Finally, in 1937, the Marxian Club was given “temporary recognition” following years of student protests and faculty support that included demonstrations in front of Memorial Union, which was not yet named for President Coffman. Dean Nicholson authorized a “free speech room,” to allow students to discuss ideas that were the focus of organizations that he refused to recognize in 1936. He again excluded any discussion of communism.“University Students Debate Political Issues in Free Speech Room,” Minneapolis Tribune, October 6, 1936, morning edition.

Propaganda Versus the Free Exchange of Ideas: Posters and Post Offices

The highly effective student activism of 1934 and 1935 led to strong sanctions initiated by Dean Edward Nicholson with the cooperation of President Coffman and the members of the Board of Regents. As a result, Nicholson was able to gain ever greater control over student activism, debate, and campus organizations through university policies that were both revitalized and extended to limit radically where and how any information for student organizations and activities could appear or be distributed on campus. Nicholson was broadly authorized to put the policies in place through President Coffman’s appointment of him; however, Nicholson made himself the central node of every strand of student life– no activity or association could exist independent of him. Nicholson:

- Exerted control over what mail could be delivered to students in campus mailboxes, not only from campus organizations but via first-class mail as well.

- Determined what constituted “propaganda,” although he never defined it to any student group that was punished for engaging in it, including student publications.

- Required his approval for every poster that appeared on campus.

- Invented a new category of student organization–partial supervision by off-campus groups–to limit members’ activities. He never defined what he meant.

In 1935, following anti-drill campus activism, the Board of Regents, at Nicholson’s suggestion, approved a resolution calling for confining “publicity material” to bulletin boards and recognized University channels. The system he initiated was sufficiently severe that students were concerned that their organizations would be unable to advertise adequately–even their dances. The number of bulletin boards where information he approved could appear was limited to nine campus locations, and nowhere else, which stopped students from posting on any wall space in buildings, hanging banners on buildings, or utilizing other public areas.

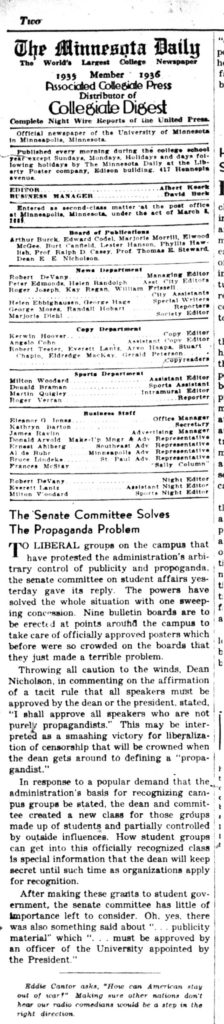

In 1936, The University Senate Committee on Student Affairs, directed by Dean Nicholson, put into place severe restrictions concerning the circulation of information to students that he deemed “propaganda.” With his encouragement, the University of Minnesota’s administration and Regents allowed Nicholson to create and implement multiple rules to further limit or withdraw rights from students for the free exchange of ideas. Dean Nicholson would now determine what constituted “propaganda.” Only information requiring his approval could be placed on nine bulletin boards on the entire campus. Finally, new policies forbade any group “with partial allegiance to an off-campus group and non-University group” to participate in student government. Nicholson never defined what propaganda was or what constituted an off-campus group.

The Minnesota Daily tracked the decisions made by the University Senate regarding limitations on student rights to distribute literature and participate in student government. The Daily also editorialized with concern about the decisions taken to limit students’ right to distribute political information.

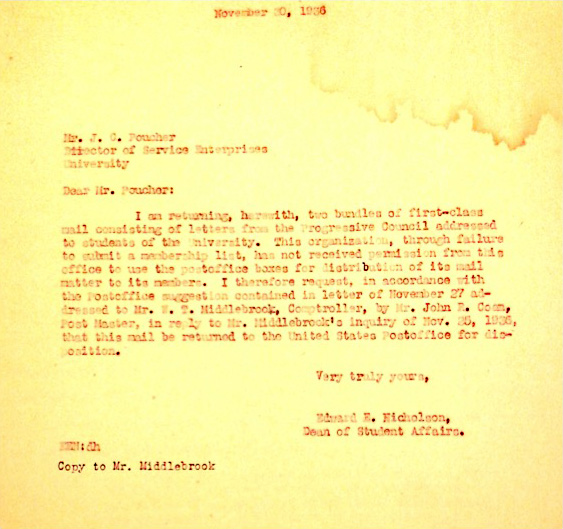

On at least two occasions, Dean Nicholson refused to distribute first-class letters to student organizations through the University of Minnesota mails. The first example is discussed in “Antisemitism at the University of Minnesota.” In 1935, the dean declared a lack of interest on the part of students in a petition that called for the United States to boycott the Berlin Olympics of 1936. German Jewish athletes were not allowed to participate because of the racist Nuremberg laws passed by the country’s Reichstag that stripped Jews of citizenship and all rights. Despite the interest of seventeen campus student organizations, and the Minnesota Daily and its readers, Dean Nicholson refused to allow mail to be distributed to campus organizations about the vote.

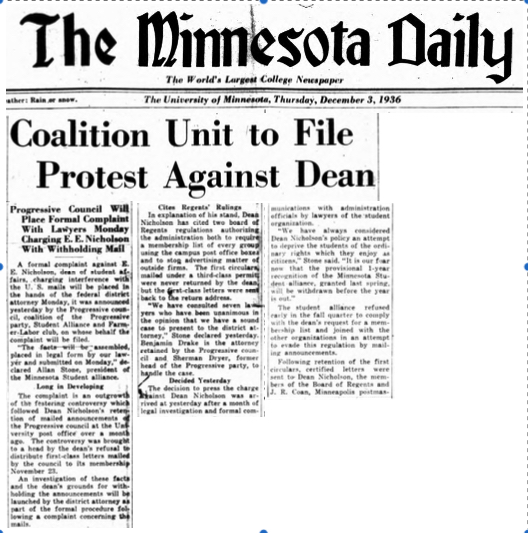

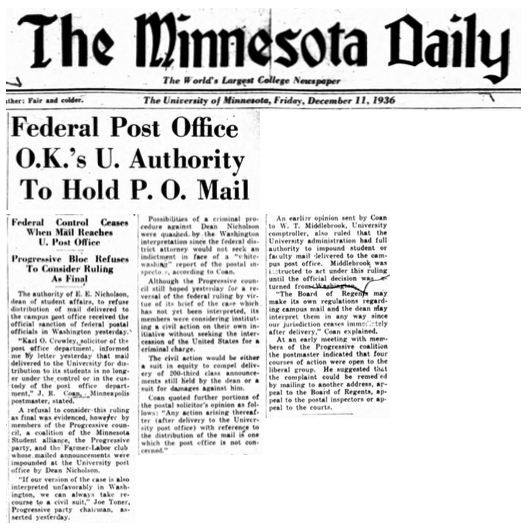

A second conflict over the censorship of mail occurred in December 1936, as reported in issues of the Minnesota Daily. It led to a group of progressive student organizations entering a “formal complaint” to the United States Attorney against Edward Nicholson for “interference with the U. S. mails.” This conflict emerged from Nicholson’s refusal to distribute circulars sent in November via third-class mail from the Progressive Council, a coalition of the Farmer-Labor Club, the Progressive Party, and the Minnesota Student Alliance. The circulars simply mentioned events and urged students to vote in upcoming student elections. The circulars were impounded by the dean. Later that month, he refused to distribute first-class letters mailed by the Council to its membership, which were instead returned to the sender. Nicholson’s rationale was that the group was an “outside firm,” defined by Nicholson for this occasion and never previously. Therefore, he claimed, these student groups were not entitled to contact students.

The students lost their lawsuit over the delivery of US mail. The United States Post Office’s solicitor ruled that once mail was delivered to the University Dean Nicholson had the right to “impound” any mail to any faculty member or student sent to the campus based on his interpretation of Regents’ policies.

The Movement for Student Reform

Between 1934 and 1936, many students active in student life, campus publications, and politics initiated a campaign for the reform, not only of student government, but student participation in University governance. They addressed many different types of issues, which led to countless debates over student voting, the selection of officers for each class, which colleges should have the greatest number of representatives on the All-University Council, and the purpose of student government itself. One proposal called for the student body president to appoint the student members of the Senate Committee on Student Affairs, a right enjoyed by President Lotus Coffman.

In April of 1936, the reform bill passed with 85 percent of the student vote. These measures were supported by the president of the All-University Council Theodore Christianson, as well as progressives and moderates. However, President Coffman and Dean Nicholson immediately challenged the students’ rights to select student members themselves. The two leaders continued to call for compromise and special committees to allow students to work with administrators. However, those attempts failed because the students were denied any autonomy, which left many of them to give up on student government.

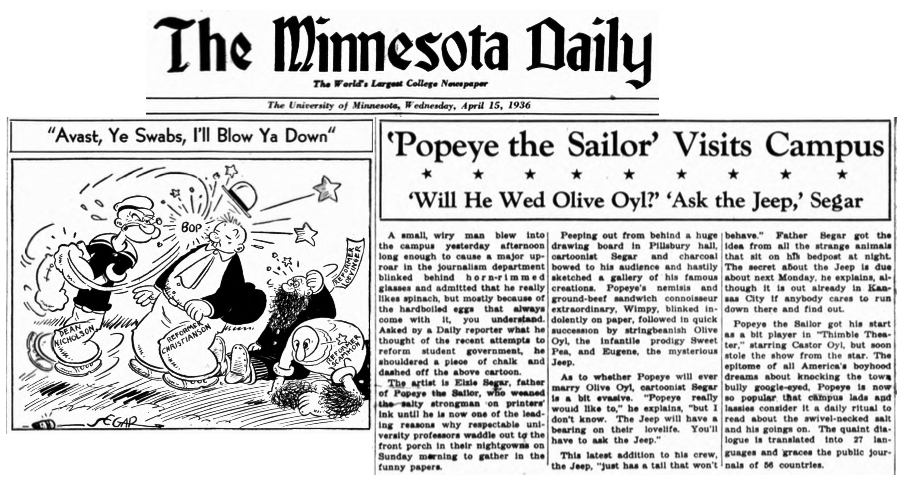

Cartoonist Elzie Segar, whose pen name was E.C. Segar, visited the School of Journalism at the university in April of 1936 at the height of the debates about student reform. Segar drew one of the nation’s most popular cartoons “Popeye the Sailor” from 1929 until his death in 1938. In 1933, Popeye was made into an animated cartoon. During a question-and-answer session with journalism students in Pillsbury Hall, Segar replied to a question from a Daily journalist about his thoughts on student reform. Mr. Segar startled his audience by rapidly drawing a cartoon on the chalk board of his Thimble Theater characters and assigning them names of students and the dean. He portrayed Dean Nicholson as Popeye taking on what he described as “student reformers” Ted Christianson as Wimpey, Richard Scammon as, Alice the Goon and Lee Loevinger as Geezil. The latter two were in conflict with Nicholson beginning in 1934. The cartoon was published in the Daily and appears on the same page as Dean Nicholson’s rebuff of any effort to allow student body president Christianson to appoint student representatives to the senate committee that the dean used effectively to control student life. Why Segar rendered the characters as he did is unclear, however the cartoon marks a powerful moment in the movement for student rights.

The Collision of Dean Edward Nicholson’s Political Life and His Position at the University of Minnesota in 1937

Dean Edward Nicholson had an active civic life. He worked closely with the most politically conservative forces in Minnesota and the Twin Cities through his leadership of the Hennepin County Law and Order League and its links with the Allied Industries and its forerunner, the Citizens Alliance. His belief in “law and order” and his fanatical opposition to organized labor and to a rainbow of left-wing organizations certainly extended to his views on student organizations.

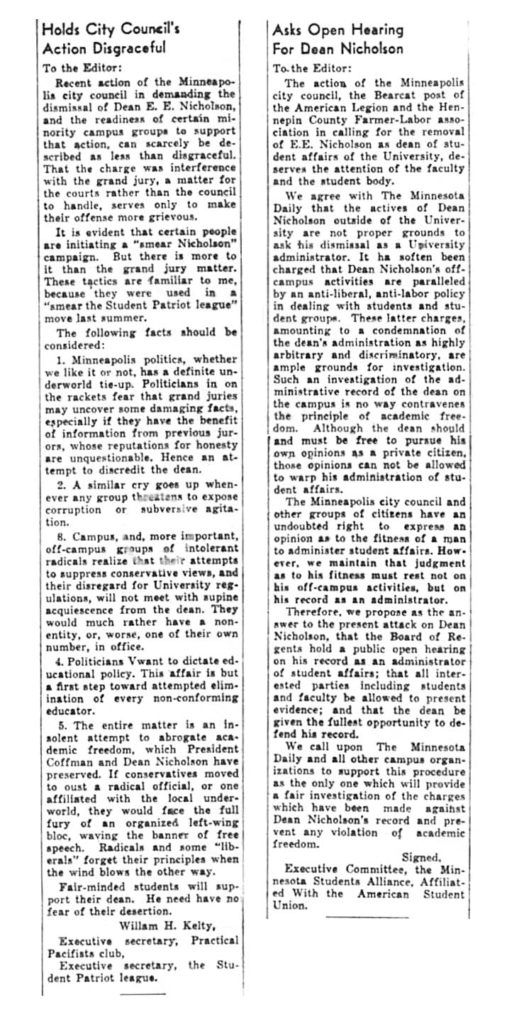

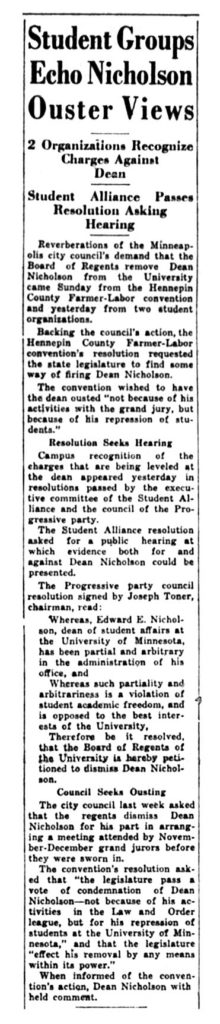

His life as a Dean of Student Affairs and a political conservative collided in 1937 when the Minneapolis City Council, in a 13-11 vote, called on the Regents of the University of Minnesota to dismiss Edward Nicholson for what was viewed as his illegal interference with a grand jury. The aldermen were divided and vociferous in their opposition to or support for Edward Nicholson.

The charge of grand jury tampering grew out of Dean Nicholson’s role in the Association of Former Grand Jury Foremen. In the Citizens Alliance’s effort to control many facets of government to realize its ambition of blocking the success of organized labor, the grand jury system played an important role. Historically, grand juries determined whether trials of citizens should go forward based on sufficient evidence and a compelling case made by the prosecution. Because cases could either be stopped before they went to trial or advanced, the grand jury played a powerful role in Minnesota politics, particularly in relation to organized labor.Robert M. Paule, “The Perversion of the Historic Function of the Grand Jury in Minnesota,” Law & Inequality 7, no. 2 (June 1989): 299-320, http://scholarship.law.umn.edu/lawineq/vol7/iss2/5.

Edward Nicholson was president of the Hennepin County Law and Order League and president of the Association of Former Grand Jury Foremen in 1936. Nicholson and his associate Charles W. Drew, head of the state’s Law and Order League, invited several grand jurors over time to meet with Nicholson for dinner, prior to their formal seating on the jury. Invitation went out on the official stationery of the Grand Jury Association. One of these dinners occurred with jurors who were to serve for November-December 1937. They had not yet been sworn in.

District Court Judge Vince Day went on the record to condemn the “interference of any super-legal organization, whether it be a law and order league or any other lawful or unlawful organization.” The State Federation of Labor called on Governor Hjalmar Petersen to investigate an attempt to control Hennepin County Grand Juries. At that point, Charles Drew had no choice but to resign as secretary of the Minnesota League for Law and Order because he had evidently compromised his office.William Millikan, A Union Against Unions: The Minneapolis Citizens Alliance and its Fight Against Organized Labor, 1903-1947 (St Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2001), 329-330, 452n17. A proposal for a new jury group was discussed in the news article “New Jury Group Hits Repeaters, Foreman Choice,” Minneapolis Star, January 9, 1937, 13. This article provides a critique of the current system and appeared the day following the call for the ouster of Dean Nicholson.

Other organizations also took stands on the matter. The Hennepin County Farmer-Labor Party and the Bear Cat Veteran’s Association, two different political organizations, supported the resolution. Both the Student Alliance and the Farmer-Labor Party wanted Dean Nicholson removed from his on-campus leadership for more reasons than the grand jury concerns. They called on the University to hold an open hearing where evidence against the dean could be presented. That hearing never took place. Nicholson was supported by the Practical Pacifists.

On January 30, 1937, President Lotus Coffman announced, following a Board of Regents meeting, that the resolution for Nicholson’s dismissal would be put “on file,” meaning filed away not to be considered again. There is no record in the minutes of the Board of Regents meetings on January 19 or January 29, 1937 of a discussion of a resolution calling for the dismissal of Dean Edward Nicholson. Nevertheless, no member of the Board of Regents nor President Coffman publicly defended Dean Nicholson and his actions.Board of Regents Meeting Minutes, January 19, 1937, University of Minnesota, retrieved from the University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy, http://hdl.handle.net/11299/45507.

Conclusion

Following Edward Nicholson’s retirement in 1941, no Dean of Student Affairs was ever again allowed to exercise his degree of control over the lives of students. The University administration was aware of the excesses of Dean Nicholson’s role in student life. In anticipation of his retirement, a Committee of Seven appointed by President Ford’s assistant, Dean Malcolm Willey was tasked with recommending the reorganization of the roles and responsibilities of the office of Dean of Student Affairs. More telling was a confidential memo from Edmund G. Williamson in 1939 when he was “Coordinator of Student Personnel Services” to Dean Malcolm Willey. Williamson would ultimately succeed Nicholson as dean two years later. He explained that

In my judgement these important phases of student life have been ineffectively supervised. Student leadership has been stifled, and to [sic] much emphasis has been placed upon control by means of authority. The control of student life by means of student mores and leadership is more promising than regulation by the authority of administrators. A desirable type of campus sociology cannot be developed if the advisers of student activities and government wield influence through their disciplinary powers. For this reason discipline should not be a function of the two supervisors [Nicholson and Anne Blitz] of student social life.Memorandum to Dean M. M. Willey from E. G. Williamson, January 24, 1939, Dean of Students, Box 12, Policy and Procedure, 1935-1946, University Archives, University of Minnesota.

Dean Nicholson created a campus environment that was challenged even from within the University of Minnesota’s administration.

The tumultuous climate of American politics and student protest in the 1930s shaped the campus of the University of Minnesota during this period. Students were remarkably successful in driving an agenda to stop required military drills and at creating powerful demonstrations against war mobilization in the United States. However, those successes were sharply curtailed on matters of student rights and freedoms for creating organizations and exchanging ideas. Dean Edward Nicholson, as well as President Coffman and Assistant Dean Malcolm Willey, were committed to the containment of a student left. Among all of these administrators, only Dean Nicholson pursued an active political life as a political conservative, and his involvement in politics found its way into campus life, both in his conspiring with Ray P. Chase on many matters and in containing student activism.