Regent George Leonard and the Political Fight Over Selecting Regents

The Political Battle to Appoint Four New Regents in 1937

Under the Minnesota State Constitution, the governor has the right to recommend candidates for the Board of Regents and the Legislature has the right to appoint the Regents. Four Board of Regents positions were available in 1937. Farmer-Labor governors Floyd Olson (served 1931 to 1936) and Elmer Benson (served 1937 to 1939) viewed the appointment of members of the Board of Regents as a critical responsibility of their offices. They wanted regents who embodied their vision for the University:

- Both supported academic freedom for faculty

- Olson opposed required military drills for all undergraduate male students

- Benson wanted to increase faculty salaries as the Depression wound down

- Both valued students’ rights to free expression in campus demonstrations

- Benson supported integrated publicly funded campus housing

- Both wanted the University to be open to students of all social classes

Conservatives in the Legislature and in the University administration insisted that the governor’s nominees for regents were “political” choices, or “tools of the Farmer-Labor Party,” while their candidates, often Republicans and conservatives, simply cared about the University. Therefore, the choice of regents throughout the era of Farmer-Labor leadership was highly contested, as it has been up to the present time.

The State Legislature that was empowered to select the four new regents for six-year appointments was divided in 1937. The State House of Representatives was primarily liberal and majority Farmer-Labor. The State Senate was primarily conservative and Republican. Was compromise possible? The battle within the Legislature and between Governor Benson and the Legislature was front-page news in the Minneapolis press from January to August of 1937.

Edward Nicholson and Ray Chase’s Campaign to Influence the Choice of Regents

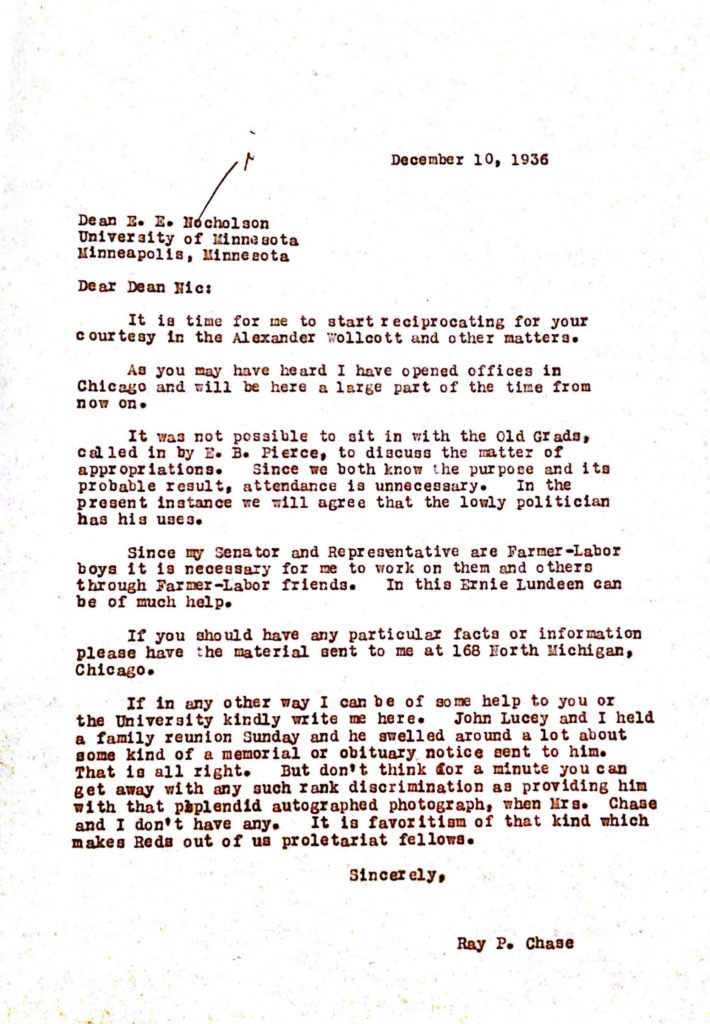

In December of 1936, Ray Chase, a Republican operative, contacted Dean of Students Edward Nicholson to offer to “reciprocate” for Nicholson’s help with “matters.” He requested Dean Nicholson to send him “facts or information” to his new office in Chicago. In turn, he offered to help the Dean, and referred to political influence with United States Senator Ernest Lundeen. The essay “Political Surveillance of the University” describes their shared political work in greater detail.

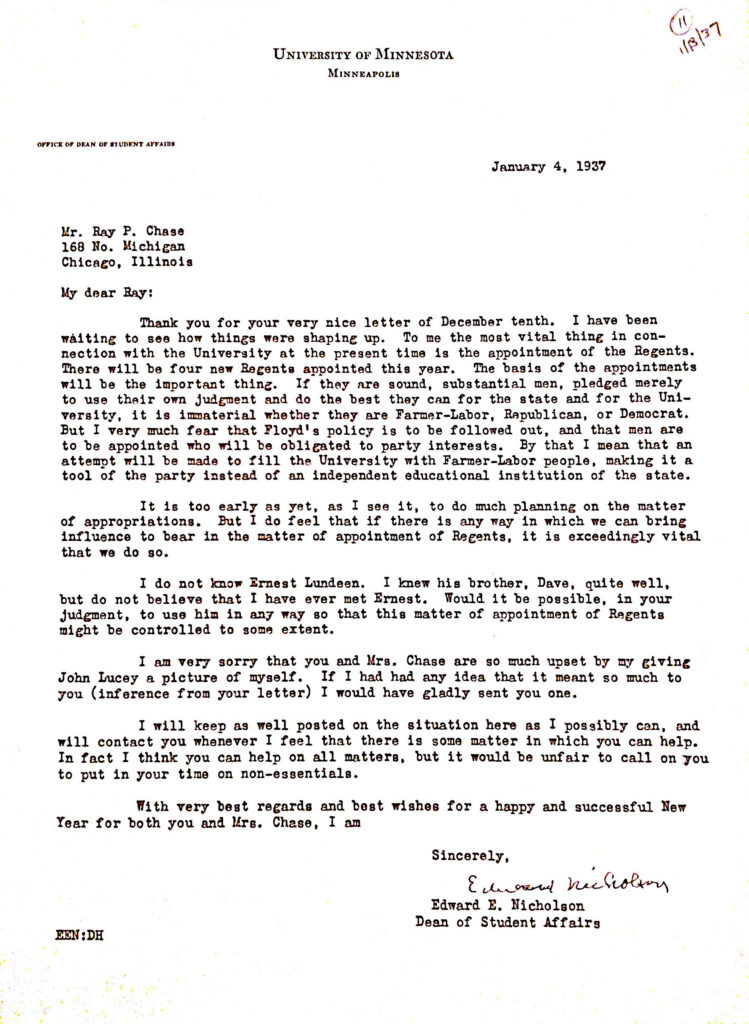

Edward Nicholson responded to Ray Chase in January of 1937 with a proposed shared agenda for affecting the University for that year. He placed the selection of the regents at the top of his list. Nicholson argued that they had to defeat the Farmer-Labor nominees. Student rights and academic freedom were not part of their shared vision for “Keeping America American.” Nicholson’s assertion that Chase can help “on all matters” is as compelling as Chase’s dependence on Nicholson for a constant stream of information about student activism that could be shaped into accusations about communism dominating the University of Minnesota.

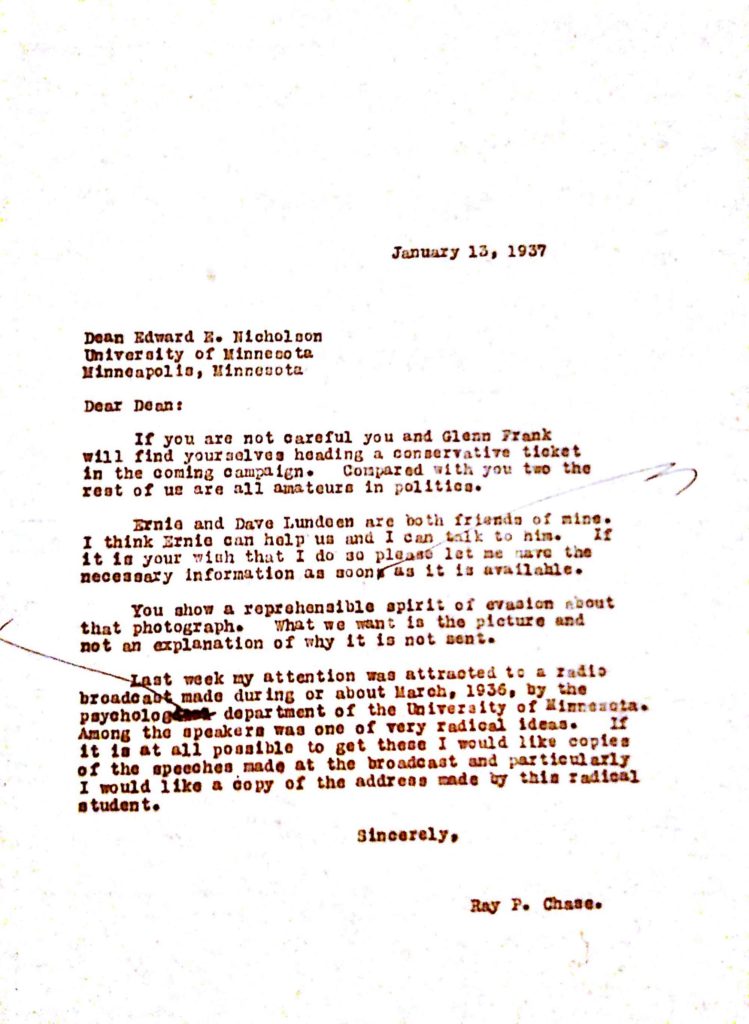

Ray Chase replied ten days later and congratulated Dean Nicholson on his acumen as a wily conservative politician. He offered to lend a hand immediately to influence Minnesota State legislators toward the choice of politically conservative and anti-Farmer-Labor regents.

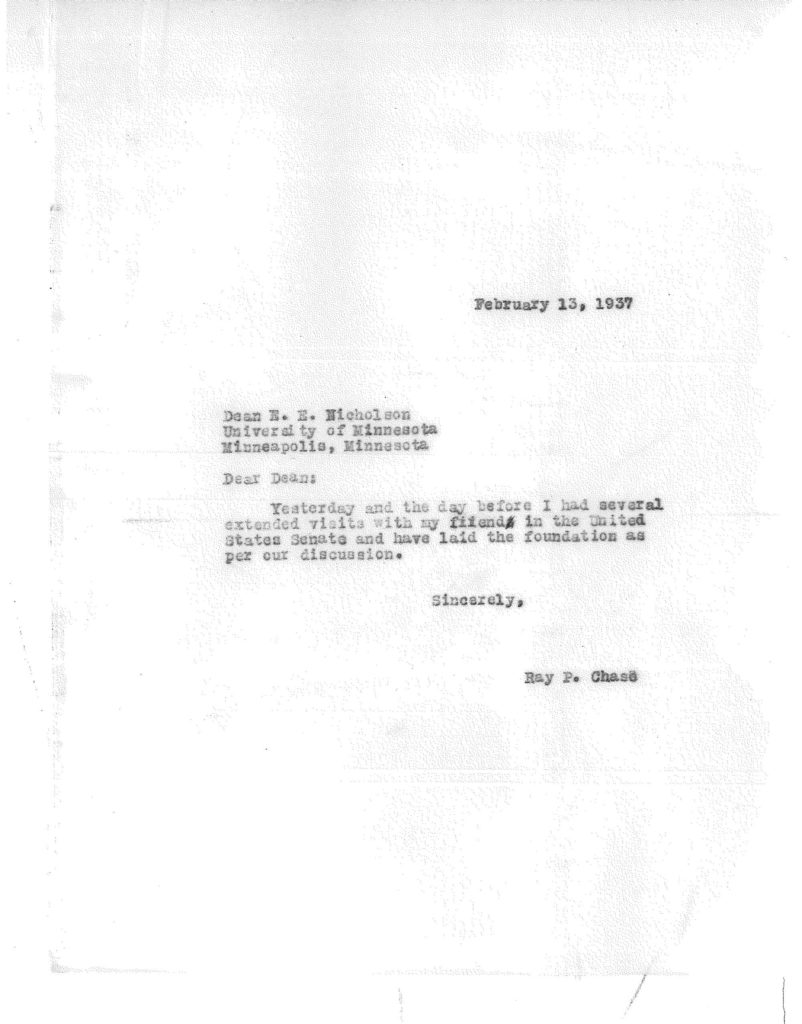

Ray Chase followed up with Dean Nicholson to assure him that he was working to influence the outcome of the choice of regents during a visit to the United States Senate.

Edward Nicholson and Ray Chase’s efforts to influence the legislative process in 1937 to ensure that politically conservative men would serve as regents belied Nicholson’s contention that he simply wanted people who would care about the University of Minnesota.

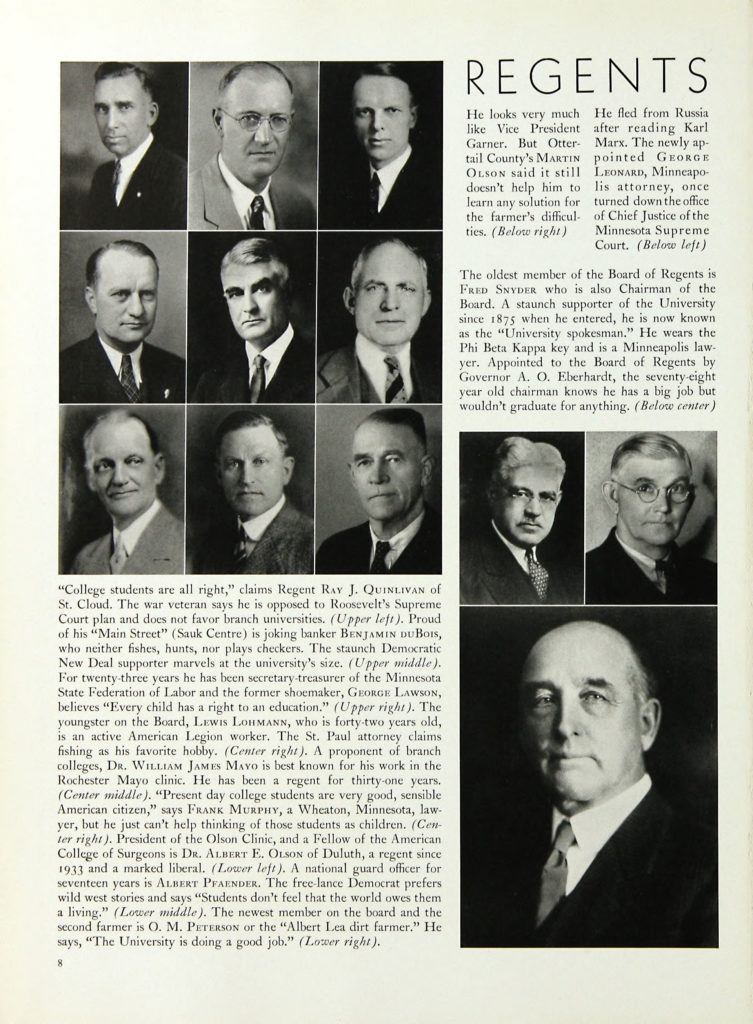

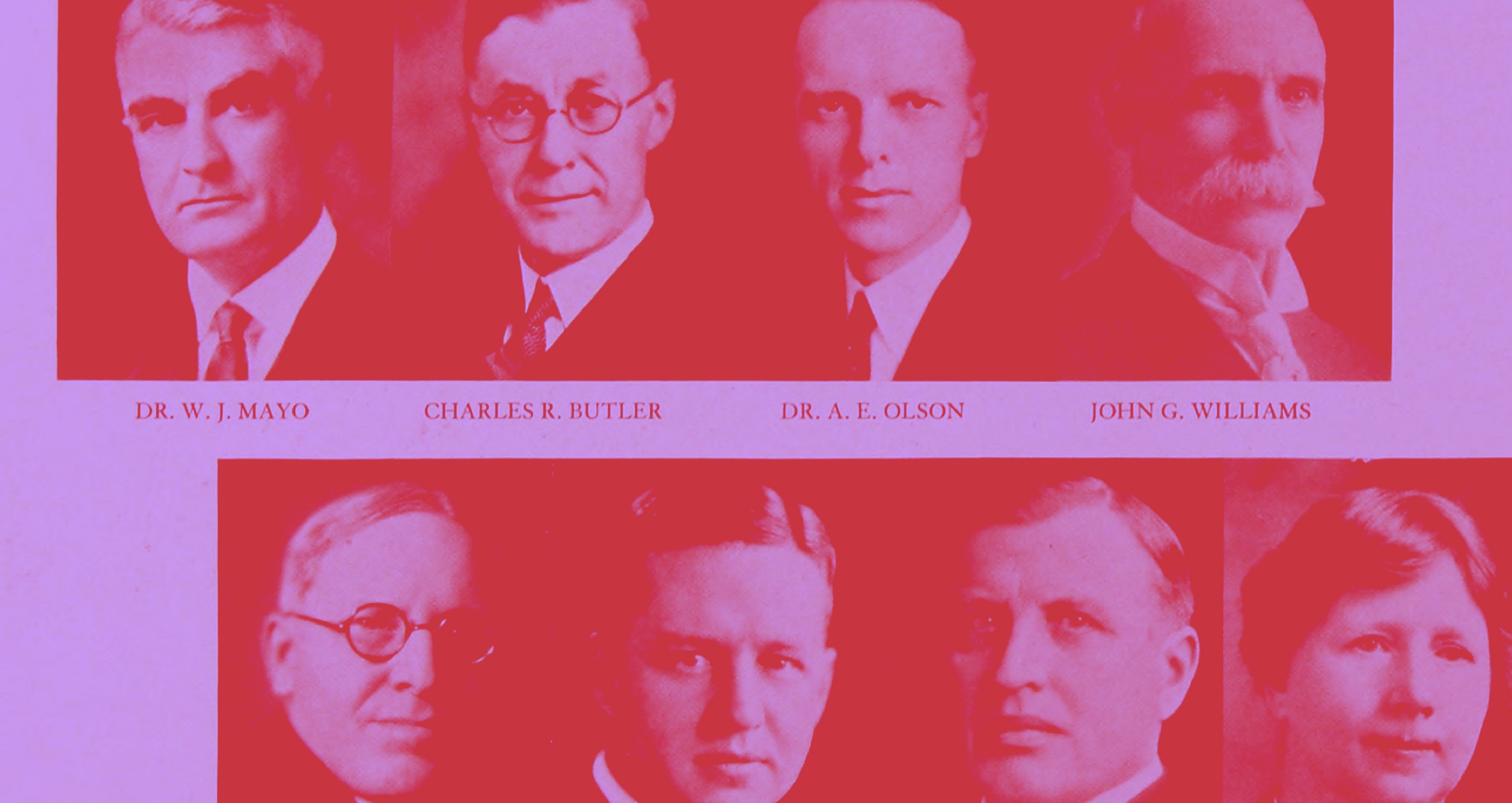

In a 1941 letter to John Lucey, Ray Chase noted that “we are now planning a little campaign to try to ensure the reelection of Shelly Wood as well as Fred Snyder to the Board of Regents.” He reported this information in a letter that described a Dad’s Association Christmas party that honored Dean Nicholson in 1930 with gifts of a “watch, chain, and knife.” Both Wood and Snyder played significant roles in the Minneapolis Citizens Alliance and its offshoots, the association of Minneapolis businesses devoted to destroying unions and organized labor throughout the 1930s.Minnesota Historical Society, Ray P. Chase Papers. Box 44 Correspondence and Miscellaneous papers January-May 1941. Fred B. Snyder, an attorney, was a founder of the Minneapolis Civic and Commerce Association and a member of the Citizens Alliance. He held a variety of leadership positions, including heading up a “Loyalty Committee.” Snyder is discussed in William Millikan, A Union Against Unions: The Minneapolis Citizens Alliance and Its Fight Against Organized Labor, 1903-1947, (St Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2001), 99, 104, 115. Snyder’s papers at the University of Minnesota archive give ample evidence of his political views. https://archives.lib.umn.edu/repositories/14/resources/1633. Sheldon Wood was the president of Electric Steel Castings, and a member of the Board of Directors of Citizens Alliance and Associated Industries in 1932.

Edward Nicholson and Ray Chase’s Campaign to Influence the Choice of Regents

Governor Benson Selected Four New Regents

The two houses of the Minnesota Legislature could not agree on four new regents despite the efforts of a joint committee to find a compromise. This impasse had happened to Governor Olson in 1935 as well. In this circumstance, Governor Benson had the constitutional right to select the regents, but only for a two-year (rather than a six-year) term. The Minneapolis Star not only featured the new appointees, but noted the political makeup of the new Board of Regents—seven appointed by Farmer-Labor governors and five who were not.

George B. Leonard and the Board of Regent’s Affirmation of Academic Freedom

George B. Leonard (1872–1956), a well-known attorney, was one of the four regents selected by Governor Benson. Regent Leonard was a close friend of Governor Floyd Olson until his death. Leonard was a founder of the Farmer-Labor Party and a lifelong defender of clean government, workers’ rights, and civil liberties. With the Urban League, he worked to integrate the University’s School of Nursing in 1933. The only public office he accepted in his long career was to serve as a member of the Board of Regents.

George Leonard was the first Jew to serve as a regent. Born in Kovno, Lithuania, he immigrated to the United States and studied law at the University of Minnesota. He founded the law firm Leonard, Street and Deinard in Minneapolis in 1922. Their firm was the first downtown law practice to hire Jewish and non-Jewish lawyers, and the first to invite a woman to serve as a partner.

William Schaper and Academic Freedom

Regent Leonard played a crucial role in realizing Governors Olson’s and Benson’s commitment to academic freedom. In 1938, the Board of Regents took up the case of Professor William Schaper, a professor of political science, who was fired from the University in 1917, five months after the United States entered WWI.

A distinguished political scientist and full professor, Schaper, who had taught at the University for 16 years, was called before the Regents because he was accused of disloyalty by a newly created Minnesota Commission of Public Safety. The Commission was empowered to assure that no citizen undermined the war effort. Schaper, the son of German immigrants, was accused of disloyalty. Regent Pierce Butler accused him of being “the Kaiser’s man.” When under questioning, Professor Schaper stated that he believed the war should be supported but that he could not “arouse the spirit of hate stirring up war hysteria.” Schaper was fired because he was “unfit” and could not “discharge his duties.”Ellen Schrecker, The Lost Soul of Higher Education: Corporatization, the Assault on Academic Freedom, and the End of the American University, (New York: New Press, 2010).

The Board of Regents revisited the case of William Schaper in 1938, who was then on the faculty of the University of Oklahoma. Schaper had the strong support of Governor Benson and many of the Regents. Schaper had been active in the Farmer-Labor Party and politics when he lived in Minnesota. When the Regents exonerated him by rescinding his firing they realized a commitment both to justice and to academic freedom.

Regent Leonard shaped the offer to Schaper that included his reinstatement as a full professor and $5,000 (about $105,000 in today’s dollars) in reparations for the loss of his salary. Schaper accepted the settlement but remained at the University of Oklahoma. The Board of Regents also accepted a resolution, now in the President Guy Stanton Ford era, that assured faculty academic freedom and due process. Professor Schaper subsequently left a bequest to the University of Minnesota’s Department of Political Science.

Conclusion

The appointment of members of the Board of Regents brought the University of Minnesota into the limelight of Minnesota politics in the 1930s. Once again, Edward Nicholson’s conservative political activism attempted to shape the University of Minnesota in ways that appeared well outside his role as an administrator. That activism is revealed only in the Chase papers, and not in his own official correspondence and papers. Nicholson concealed his activism, hiding it from public scrutiny.

The Farmer-Labor Party sought different types of regents. George Leonard’s brief tenure as a regent brought about a number of important changes. Leonard was particularly proud of his role in the University’s giving restitution to William Schaper for the miscarriage of justice in his firing in the midst of the political repression and suspension of civil liberties of WWI authorized by the Espionage and Sedition Acts. The only regent who voted against the acknowledgement of the miscarriage of justice was Fred B. Snyder, Ray Chase, and Edward Nicholson’s candidate and longtime Republican political activist.