What Happened to the Student Activists who Challenged Racism, Antisemitism, and Political Repression?

From the records of University of Minnesota administrators and Republican operative Ray P. Chase, many of the following names represented “problem” students whose presence and work throughout the 1930s disrupted or threatened campus life and who posed threats to the state and the nation. Some students, particularly Jewish and white individuals, were directly targeted as “radicals” or “Communists.” Others, particularly African American students, were only singled out when their work challenged campus segregation and anti-African American policies.

Several of these students appeared on a list entitled “Radical Students” created by Republican operative Ray P. Chase based on information provided by Dean of Student Affairs Edward E. Nicholson. Chase apparently shared these names with the FBI and other agencies. You may learn about the lists in the essay for this website “Political Surveillance of the University of Minnesota.”

These outstanding young activists, in their individual and collective lives, remained committed to equity and justice and called on the nation to live up to its ideals. Their varied careers and diverse callings represent the many ways they continued the commitment they made as early as the 1930s when they used their power as students to shape the world that they wanted to inhabit. They are outstanding alumni of the University of Minnesota, although few of them have received sufficient recognition.

If you have information about any of these men and women that would add to their biographies, please contact us at prell001@umn.edu.

Lester Breslow

1915–2012

As a student, Lester Breslow was one of the leaders of the anti-war movement, both nationally and on the campus, and objected to the segregation of the first men’s dormitory Pioneer Hall. He appeared on the Chase lists from his undergraduate days through his appointment as a physician at the University, and was listed as “son of druggist. Russian Jew.”

He graduated from the University of Minnesota Medical School in 1938 and received a Master’s of Public Health in 1941. He became interested in public health because, he said, he thought it suited his ideology as “a political activist for disadvantaged people.” In 1943 he joined the Army, even though his job and having a young child both exempted him from the World War II draft. He wrote that he felt guilty because earlier he had not joined the “anti-fascist struggle” by volunteering to fight in the Spanish Civil War. He served in the Pacific as a captain.

Breslow advised a half-dozen presidential administrations and was director of the California Public Health Department in the mid-1960s. Governor Ronald Reagan fired him in 1967, citing “philosophical differences” over state cuts in medical care for the poor. He then served as Dean of the School of Public Health at UCLA. His research transformed the field of public health. Among his most significant work was demonstrating the impact of lifestyle on longevity.

You can look back to Breslow’s activism by viewing “Student Movements on Campus and the Struggle for Students’ Rights” and “Political Surveillance of the University.”

Charlotte Crump (Poole)

1918–1990

As a student, Crump was a founder of the Negro Student Council and an activist around segregated campus housing. She ran for Senior Class President on the Progressive Party ticket in 1938, likely one of the first African American students to participate in campus electoral politics. She also served on the Gopher yearbook staff. Crump was reprimanded by Dean of Women Anne Blitz for calling attention to campus racism in her article “This Free North,” published in a supplement of the Minnesota Daily, in which she boldly called out racism on campus.

After graduation, Crump became a journalist and wrote for the Pittsburgh Courier. She served as the Director of Information with the national office of the NAACP. In California, where she lived with her family, she founded the Jack and Jill of America organization and advocated for families and children, particularly on behalf of African American children.

You can look back to Crump’s activism by viewing “Segregated Student Housing and the Activists Who Defeated It.”

Sherman H. Dryer

1913–1989

As a student, Dryer was in the leadership of the Minnesota Daily, headed a new literary magazine, and worked at the campus radio station WLB. He was a political activist in the politically progressive Minnesota Student Alliance. He was one of the leaders of efforts to allow students to be able send mail to student mail boxes, something Dean Edward Nicholson blocked. Chase described him as “Jew. Communist. Agitator and Publicist.”

Dryer was a speechwriter for Governor Elmer A. Benson and active in the Farmer-Labor Party. He was smeared by Ray Chase in his Red- and Jew-baiting campaign against Benson in the 1938 gubernatorial race. Dryer went on to a distinguished career in radio and received a 1941 Peabody Award for the University of Chicago’s “Round Table of the Air.” He produced a number of science fiction type programs through the 1950s.

You can look back to Dryer’s activism by viewing “Student Movements on Campus and the Struggle for Students’ Rights” and “Political Surveillance of the University.”

Warren Valdo Grissom

1911-1983

As a student, Grissom was an important leader of the effort to integrate campus housing. He chaired the Interracial Committee, which was affiliated with the Negro Student Council, and authored its report. After graduating from the University in 1938, Grissom went on to serve as a Merchant Marine during WWII and earned his Master’s of Science in Social Work at Boston University in 1947. Grissom settled in Ohio, where he was assistant director of the Wood County Mental Health Clinic in Bowling Green.

You can look back to Grissom’s activism by viewing “Segregated Student Housing and the Activists Who Defeated It.”

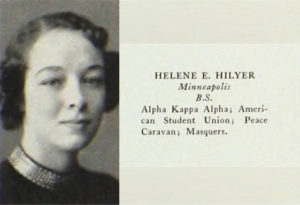

Helene Hilyer (Hale)

1918–2013

As a student, Hilyer was active in the effort to integrate campus housing and was an activist for peace. She was the granddaughter of the first African American man to graduate from the University of Minnesota, Andrew Hilyer, who graduated in 1882. Her father, Gale Pillsbury Hilyer, also graduated from the Univesity of Minnesota. Helene Hilyer, who graduated in 1939, studied education, English, sociology, and speech with the intention of becoming a teacher. She could not get a job anywhere in Minnesota because she was African American. She taught in Nashville, Tennessee at Tennessee A&I State College. Hilyer and her husband William Hale moved to New York, where he helped to organize a 1941 March on Washington to demand that African Americans be awarded jobs in the defense industry. The threat of the protest resulted in the demands being met, and the demonstration was never held.

She became a youth secretary for the Fellowship of Reconciliation, which was committed to nonviolence and interracial work.

Hilyer and Hale moved to Hawaii in 1947 and taught in Kona, became active in the Democratic party, and were supporters of statehood. Hilyer was the first woman and the first African American to be elected to serve as both a county supervisor and the mayor of Hawaii County.Helene Hilyer (Hale), interview by Chris Conybeare and Daniel W. Tuttle, Jr., Hilo, Hawai’i, May 25, 1988, Tape No. 17-57-1-88, transcript, Hawai’i Political History Documentation Project, Center for Oral History Social Science Research Institute, University of Hawai’i at Manoa, https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/cfa77025-dcd7-4552-ae1f-f7adf9763268/content.

You can look back to Hylier’s activism by viewing “Segregated Student Housing and the Activists Who Defeated It.”

Howard Kahn

1915–2008

As a student, Kahn chaired the first All-University Council Committee on Negro Discrimination, which recommended the integration of University dormitories in 1935. He supported that position as a student member of the Board of Regents. He was a chemist by training and received an undergraduate and master’s degree in chemistry from the University of Minnesota in the late 1930s. He worked on housing and civil rights for his entire life. In the 1940s and 1950s, he was chairman of the Minneapolis Housing Association and the Mayor’s Advisory Committee on Housing in addition to serving on the Mayor’s Commission on Human Rights. Kahn was also a board member of the Jewish Community Relations Council.

You can look back to Kahn’s activism by viewing “Segregated Student Housing and the Activists Who Defeated It.”

Garland D. Kyle

1905–1971

As a student, Kyle led the effort to integrate the “International House,” where he was assigned to live. Kyle came to the University with both an undergraduate and master’s degree, seeking his PhD in mathematics. Having already traveled to 43 states, Kyle was astonished at the segregationist practices of the University administration. After leaving to serve as a civil servant in the Navy during WWII, Kyle returned to Minnesota and graduated in 1947. He went on to a long career as a Professor of Mathematics and Dean of the Department of Mathematics and Physics at the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff, a historically Black university (formerly Arkansas Agricultural, Mechanical and Normal College). Today, the Kountz-Kyle Science Hall stands on the campus in his honor.

You can look back to Kyle’s activism by viewing “Segregated Student Housing and the Activists Who Defeated It.”

Lee Loevinger

1913–2004

As a student, Lee Loevinger was part of the group that led the opposition to mandatory ROTC on campus and antiwar activism in the early 1930s. He chaired the student Board of Publication that oversaw the Minnesota Daily at a time when the student newspaper was critical of the University administration and strongly favored student activism. Loevinger was a member of the Jacobins, a group of student activists who were involved in student government, journalism, and antiwar activism. He graduated from the University of Minnesota in 1933 and from the Law School in 1938. He joined the Navy in 1942 and served in North Africa and Europe. After the war, he worked as an attorney and was appointed an Associate Justice of the Minnesota Supreme Court, where he served for one year. In 1961, he became an Assistant Attorney General in the Antitrust Division of Robert Kennedy’s Justice Department. After nine years on the Federal Communications Commission, he went into private practice.

You can look back to Lee Loevinger’s activism by viewing “Student Movements on Campus and the Struggle for Students’ Rights” and “Segregated Student Housing and the Activists Who Defeated It.”

Robert Loevinger

1916–2005

As a student, Robert Loevinger, Lee’s younger brother, was centrally involved in the first efforts to integrate student housing. He served on the All-University Council Committee on Negro Discrimination, which recommended the integration of University dormitories in 1935. He was involved in many left-wing political groups on campus, and Chase branded him a “campus agitator and Marxist…Jew.” He graduated from the University of Minnesota in 1937.

During World War II, he worked as a graduate student at the University of California on the Manhattan Project, the government’s effort to develop a nuclear weapon. He became a medical physicist after completing his degree there and later joined scientific organizations that promoted the peaceful use of nuclear technology. He served as the chief of the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s dosimetry section, where he greatly advanced the use of x-ray measurements in radiation treatments, making them safer and more reliable for cancer patients. He received many awards for his work.

You can look back to Robert Loevinger’s activism by viewing “Student Movements on Campus and the Struggle for Students’ Rights”, “Political Surveillance of the University”, and “Segregated Student Housing and the Activists Who Defeated It.”

Norman P. Lyght

1913–1993

As a student, Lyght was not allowed to reside in Pioneer Hall because he was African American, despite holding a federal scholarship that required an on-campus residence. He was a member of the Negro Student Council. He served in the U.S. Army 2nd Division as a Lieutenant in WWII.

You can look back to Lyght’s activism by viewing “Segregated Student Housing and the Activists Who Defeated It.”

Rosalind Matusow (Belmont)

1917–?

As a student, Matusow was an anti-war activist and member of the American Student Union. She sought recognition for a Marxist club without success and was thus included on Chase’s lists of subversives. She took time off from her studies to unionize hotel maids for Local 665 of the Hotel and Restaurant Worker Union and supported other unionizing efforts. She completed a degree in public health nursing and remained a nurse for her career in California. She is included in the Minnesota Historical Society’s Twentieth Century Radicalism in Minnesota Oral History Project.

You can look back to Matusow’s activism by viewing “Student Movements on Campus and the Struggle for Students’ Rights” and “Political Surveillance of the University.”

Esther Leah Medalie (Ritz)

1918–2003

As a student, Medalie led the American Student Union and was an anti-fascist. Edward Nicholson gave her name to the FBI in 1941 because of her affiliation with the ASU, and she was included on a Chase list. She was the first woman on the editorial board of the Minnesota Daily and specialized in writing editorials about international relations and interracial issues. She graduated in 1940. Medalie lived in Milwaukee, Wisconsin and initially worked for the Office of Price Administration until she had children. Thereafter, she held international and national offices in Jewish communal organizations. She was active in Middle East peace efforts and attended the first dialogue of native and diaspora Palestinian and Jewish women leaders. She received many awards for her involvement in civil rights, human rights, consumer rights, and for women’s advocacy and environmental protection programs.

You can look back to Medalie’s activism by viewing “Political Surveillance of the University.”

John R. Pinkett, Jr.

1914–1966

As a student, John Pinkett came to the administration’s attention when he registered for housing in Pioneer Hall and was the first African American student excluded from campus dormitories. He remained on campus for the year, but Pinkett then returned to the greater Washington D.C. area. He began an all-Black flight school called the Cloud Club because aspiring African American pilots were denied flight instruction elsewhere. When the war began, he served as a flight instructor in Alabama making him a Tuskegee airman. Pinkett went on to achieve the rank of captain in the Air Force. He found a second career helping to run the family-owned John R. Pinkett, Inc. real estate business. Pinkett worked to integrate upper-income neighborhoods in Washington, D.C. In doing so, he was known to “bear the brunt of any neighborhood reaction”–he had a cross burned on his lawn and had windows broken with bricks on more than one occasion.

You can look back to Pinkett’s activism by viewing “Segregated Student Housing and the Activists Who Defeated It.”

Richard M. Scammon

1915–2001

As a student, Scammon’s name appeared on Chase’s lists along with other “radical leaders” for his leadership of the anti-mandatory ROTC and anti-war movements. He belonged to the student group the Jacobins. He graduated from the University of Minnesota with a degree in political science in 1935. He served as a captain in the Army during WWII. Scammon was a political scientist, writer, and a scholar of elections; worked for both the Army and the State Department; and served as Director of the U.S. Bureau of the Census from 1961–1965. He was a personal advisor to Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson during his time as head of the Commerce Department’s Census Bureau. He directed extensive election-night coverage for NBC News in 1968 and advised the network until 1988.

You can look back to Scammon’s activism by viewing “Student Movements on Campus and the Struggle for Students’ Rights” and “Political Surveillance of the University.”

Arnold Eric Sevareid

1912–1992

As a student, Arnold Eric Sevareid (who later dropped his first name) was a leader of the anti-drill movement and anti-war activism. As a writer for the Minnesota Daily, he covered these events as well. He was a member of the Jacobins. He was denied the editorship of the paper, he believed, as a result of his political stands. As an undergraduate he worked for the Minneapolis Journal, one of the city’s newspapers, and wrote a multi-part series on the fascist Silver Shirts, which also angered Ray Chase, who included him in his lists of “radical students.” He graduated in 1935. Sevareid’s distinguished career as a war correspondent, journalist, and pioneer in network broadcasting made him one of his generation’s most significant journalists.

You can look back to Sevareid’s activism by viewing “Student Movements on Campus and the Struggle for Students’ Rights” and “Political Surveillance of the University.”

B. Warner Shippee

1916–2005

As a student, Warner Shippee was active in anti-drill and anti-war activism, and a Jacobin who challenged the University’s administration. He was one of the first students to claim that as a conscientious objector, he should be allowed to substitute physical education for military drills. He was active in a number of left-wing student groups and tangled with deans in his effort to seek approval for them to be recognized as acceptable groups. He graduated in 1935.

Shippee’s career focused on housing, redevelopment, and city planning. He served as Executive Director of the Saint Paul Housing and Redevelopment Authority and worked within the Center for Urban and Regional Affairs at the University of Minnesota.

You can look back to Shippee’s activism by viewing “Student Movements on Campus and the Struggle for Students’ Rights.”

Joe Toner

1917-2004

As a student, Joe Toner was a member of the Interracial Committee of the Negro Student Council and a signer of the Grissom Report on segregated housing. He was a vice-president of the All University Council and organized against the segregated International House. He was listed among Chase’s radical leaders.

Joe Toner found a home at the Minnesota School of Journalism and the Minnesota Daily, the rare setting where Jewish and non-Jewish students worked comfortably together. In addition to his work on racial equality on the All University Council, he worked to bring five or six oppressed student refugees from Spain, China, Czechoslovakia, and Germany to campus.

He completed a Master’s degree in Public Administration at Syracuse University and enlisted in the Army immediately thereafter. He served in Bougainville and the South Philippines and was awarded the Bronze Star.

A life-long Progressive, he spent his career in public service. He was Executive Secretary of the organization that became the Foreign Operation Administration. In 1952, he served as the secretary of the Foreign Operation Administration, and in 1955, he moved to the White House Disarmament Staff. Among his other positions was working for the Agency for International Development. For fourteen years, he worked overseas, dealing with some of the most difficult global problems–war, genocide, famine, the Cold War–among many others. In 1978, he was awarded AID’s Distinguished Honor Award.

You can look back to Toner’s activism by viewing “Student Movements on Campus and the Struggle for Students’ Rights”, “Political Surveillance of the University”, and “Segregated Student Housing and the Activists Who Defeated It.”

Arnold B. Walker

1909-1988

As a graduate student in sociology at the University, Arnold Walker served as a founder and president of the campus Negro Student Council. He and other students led the effort to end segregation in campus housing. After graduation, Walker moved to St. Louis, Cincinnati, and then Cleveland, where he was an active leader within these cities’ chapters of the Urban League. Walker served as the Executive Director of the Cleveland Urban League from 1945-59, where his efforts to secure suitable housing for African Americans continued.

You can look back to Walker’s activism by viewing “Segregated Student Housing and the Activists Who Defeated It.”

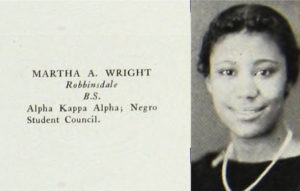

Martha A. Wright (Wilson)

1919–2010

As a student, Wright was a president of the Negro Student Council, a member of its Interracial Committee that worked for integrated student housing, and active in Alpha Kappa Alpha, the African American sorority. After receiving a degree in mathematics in 1938, she learned that no African American was allowed to teach in the Minneapolis school system. Wright went on to a career in higher education at Savannah State College in mathematics and eventually served as Dean for Undergraduate studies and as Acting Vice-President for Academic Affairs after her formal retirement.

She had an additional career of civic and religious service for which she received many awards. She co-led, with the other founders of a local chapter of Alpha Kappa Alpha, the opening and expansion of what came to be called the Greenbriar Children’s Center for homeless and neglected children in Savannah, Georgia. Wright was also active in a wide range of organizations that advocated for human rights, women, and children. She was a national and state leader in the Episcopal Church, breaking boundaries as a woman and an African American.

You can look back to Wright’s activism by viewing “Segregated Student Housing and the Activists Who Defeated It.”